Lately, I’ve been obsessed with this idea of the “pendulum swinging back”.

For the past decade, the regional music industry has been in an almost obsessive state of acceleration. At some point, it was no longer about just making music; it was about building something, proving something, arriving somewhere. The independent scene had to establish itself, to stake its claim in the global industry, to break the regional ceiling and stand alongside international movements.

Everything felt like a first. There was urgency and hunger. Music wasn’t an end in itself—it was a means to an end, a vehicle for recognition, for visibility, for success.

But something got lost along the way.

There was a time when bands ruled the region. From the golden age of Arabic rock and fusion bands to the explosion of alternative acts in the 2000s and early 2010s, they were the backbone of the indie scene. But then, almost suddenly, the momentum stopped. The era of the band collapsed.

Post-Cairokee in their heyday, things started to shift. The rise of artists like Abyusif signaled a new reality: the individualist era had begun. You now only needed a mic, a laptop, and an internet connection to make a hit. Suddenly, bands seemed impractical, cumbersome. They were slow-moving, expensive, and not built for the DIY hustle that was taking over. The craft of band-building—long rehearsals, layered songwriting, the inefficiency of collaboration—felt like a relic from a slower era.

Music moves in cycles. The shift toward individualism wasn’t just about accessibility or technology; it was also a response to these limitations. Bands require time—to rehearse, write together, develop synergy. They require space—instruments, studios, physical presence. They require commitment—long-term creative relationships that aren’t as flexible as one-off collaborations.

Enter trap, techno, and club music. These genres were fast, nimble, self-sufficient, and built for digital virality—everything a band was not. It wasn’t just that bands disappeared—they also became less economically viable. Venues prioritized DJs over live bands because they were cheaper and took up less space. Streaming culture rewarded singles, making long, collaboratively written albums feel impractical. Labels and festivals focused on solo stars who could be more easily marketed, booked, and exported globally.

Music became optimized for an industry built around speed, algorithms, and solo personalities. The role of music itself shifted—it was no longer about songs that lasted decades, but about tracks designed for the moment. The business of music had caught up to the algorithm era. The proliferation of social media accelerated everything even more. The industry became a machine of content over craft, speed over depth, visibility over intention. Social media was not just shaping how music was being consumed; it was dictating how it was made.

Then came COVID-19, a moment that, instead of forcing a reset, only intensified the focus on individualism. With live music shut down, digital content took over completely. Music became a game of who could stay in the conversation the longest. Social media, streaming algorithms, and short-form content have made music feel disposable. There’s a sense that we’re more connected than ever, but the experience of music—particularly live music—has become more passive.

And in the years that followed, the MENA industry became obsessed with milestones. The first rapper to sell out a festival. The first Arab artist to land a global sync deal. The first DJ from the region to break the Boiler Room circuit. The first, the first, the first. It was a necessary phase—these achievements built the industry. They put the region on the map. But once all the “firsts” were done, once the doors had been opened…then what?

That’s the thing about acceleration—it can’t last forever. And now, the pendulum is swinging back.

Bands are re-emerging—not as a nostalgic revival, but as a reactionary movement. Their return signals a realignment of the industry’s priorities. After years of chasing visibility and desensitizing our ears online, there’s a renewed focus on craft. Maybe we swayed too far in one direction, but now we crave the synergy of playing together, engaging off-screen, watching instruments and voices synchronize and harmonize in real time. The infrastructure that once made bands impractical—lack of support, economic pressures, and hyper-digitalization—is no longer as hostile. Music is returning as a craft, not just a commodity.

In 2025, this could mean a return to structure—not just loops and hooks, but evolving compositions. More experimentation, as bands naturally create space for live improvisation. This isn’t to say hip-hop and electronic music haven’t innovated or honed their craft over the last decade. But their fast, lightweight nature made them the perfect vehicle to push the industry forward. As the pace accelerated and social media took over, the market became oversaturated with easily consumable music—floods of singles, short EPs, and bite-sized promotional content that left listeners overstimulated yet disconnected.

At its core, this shift is about more than just music—it’s about social media. People now crave longer-form, more intimate content. They want behind-the-scenes access, real-time creation, and deeper connections. This makes fertile ground for bands to creep back in. Audiences are looking for the process to unfold before their eyes—music harmonizing live, not just the polished end product of a studio session but the raw, in-the-moment experience of a band playing together.

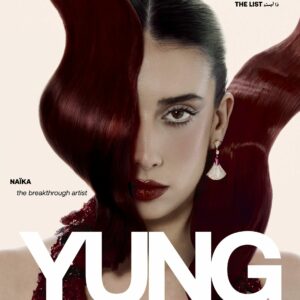

And you can feel it everywhere. 2024’s breakthrough artist Tul8te re-emerging and performing with a full band ensemble, indie labels taking a chance on acts that, five years ago, wouldn’t have stood a chance in the industry’s breakneck economy. In the subtle shift happening even within hip-hop and electronic music, where live instrumentation is creeping back into performances, where artists are moving away from the beat-driven, loop-heavy structures of trap and techno. We’re seeing a resurgence of pop, indie, and songwriting-focused music.

It’s not about music. It’s about the exhaustion of content culture. Music has been a means to an end. A functional tool for an artist’s career, a way to climb, a way to stay visible.

For the first time in years, the MENA music industry has nothing left to prove. The groundwork is laid, the industry exists, the world is paying attention. The hunger for validation is gone. And in its place? A hunger to make something real.

The exhaustion of social media, the collapse of engagement-based art, the craving for something more immersive—it’s all connected. We’re seeing a shift toward music that asks for attention rather than fights for it. Bands, live acts, and compositions that unfold in real time serve as a reminder that music isn’t just another piece of content to be scrolled past. At its best, it’s an experience—something that can’t be condensed, packaged, or algorithmically optimized. And that’s exactly why it’s making a return.

For more stories of regional music, visit our dedicated archives and stay tuned in to our Instagram feed.