Social media has quietly, yet almost completely, I would argue, rewired the way we live. It has altered how we make friends, the way we interact with each other, and even how we measure the worth of our own lives. We no longer simply experience moments as they come in the now. We frame them, we polish them, we break them up and offer them into the feed as strategically timed, aesthetically pleasing carousels, seamlessly edited reels, self-deprecating stories disguised as humorous, cool memes. A shot of a bird on the beach followed by a designer handbag perched obscurely by a tree. A carefully chosen “quirky” moment. Each post is an entry in a personal archive that says: “I’m still here. I’m still relevant. I still matter.”

It is an endless fight for visibility in an ecosystem that has no problem erasing you the moment you decide to go quiet. We all know the algorithm does not reward rest. We see it when we decide to go offline for even a day or two: the dip in engagement, fewer messages coming through. It rewards constant motion and constant performance.

And for the creatives, this creates a brutal paradox: our minds and hearts need pause, boredom, and long stretches of quiet to create, to be— yet our survival now depends on relentless output. It’s not enough to make something meaningful and trust it will find its people. You have to actively vie for space in someone’s crowded feed. Visibility is survival now.

This has transformed music in ways we barely stop to question. A single is no longer just a single. It is now a campaign. It must be atomized into multiple pieces of content: reels, carousels, teaser clips, lyric videos, behind-the-scenes stills, cover art reveals. Each post is not necessarily always chosen to best represent the song’s emotional truth. Rather, it is chosen to maximize reach, to keep the algorithm warm.

And while, yes, I will admit that this has opened up a lot of creative possibilities. A music video can be its own art form, cover art can be striking, behind-the-scenes reels can connect us to fans in meaningful ways. And that in and of itself is not something that should be discounted. But at the same time, it has also made these things a necessity rather than a choice.

I think the difference is critical. When you want to create extra layers around a song, it’s expression. When you must do it or risk invisibility, it takes on the form of survival labour. What was once an optional canvas for experimentation becomes another box to tick, another drain on time, money, and energy often before the song itself has even had the chance to take its first breath.

This is the unspoken cost a lot of artists are forced to take on. When every song is treated as a multi-post content machine, there’s less space for the kind of work that requires subtlety, patience, or delayed impact. Not every song should need an onslaught of messaging to be heard.

Recently, I noticed a trend that has been gaining traction in music: the waterfall release strategy. For those unfamiliar, waterfalling is when an artist has a complete project, either an album or EP, but instead of releasing it all at once, they drip it out track by track over time, often adding each new song to the same streaming playlist until the full project is available.

On paper, it is smart and many might even argue, necessary. Streaming platforms like Spotify love it. Their algorithm rewards repeated “new” uploads, even if the songs have already been released. Each fresh drop revives the older tracks, boosting playlist placements, Save Rates, and those coveted “Discover Weekly” appearances. Artists use waterfall releases to build momentum, grow streams and audiences steadily over months instead of banking everything on a single release day.

Across music history, artists have always adapted their release strategies to survive within the dominant distribution systems of their time. The format may change, but the instinct is the same. You must find a way to stay visible, cut through the noise, and reach listeners where they already are.

In the 1950s and 1960s, that meant embracing the single. Radio airplay and jukebox rotations dictated success, so labels pushed one track at a time. Albums were often afterthoughts. They were usually bundles of proven singles rather than cohesive artistic statements. The goal was to feed the machine that controlled discovery.

By the time the 1970s and 1980s rolled around, mixtapes emerged as a new survival tool, this time from the grassroots up. In early hip-hop communities, DJs and MCs recorded live sets onto cassettes, often without authorization, passing them around locally. These tapes were portable and outside the industry’s control. Through the ’90s and 2000s, artists like 50 Cent, Lil Wayne, and Drake used mixtapes to bypass label gatekeepers entirely, experiment creatively, and build buzz directly with audiences. Even as the internet expanded their reach through platforms like DatPiff and SoundCloud, the underlying strategy was the same: adapt to the channels that could deliver ears, whether sanctioned or not.

Today’s equivalent is waterfalling. On the surface, it echoes the single culture of the ’50s or the slow-build mixtape drops of the ’00s. But the driving force is different. In our social media and streaming age, the gatekeeper is no longer a DJ or a radio programmer. It is all about the algorithm – an opaque, data-driven system optimizing for engagement metrics. It’s survival in an attention economy where constant novelty outranks cohesive storytelling.

The crucial shift is while singles were tailored for radio and mixtapes thrived in community networks, waterfalling often begins as a post-production marketing decision. It’s less about creative urgency and more about engineering sustained visibility. That doesn’t make it inherently soulless. It is simply the modern survival strategy, shaped by the infrastructure of our era. The through line remains the same. Artists adapt to the rules of the game. The only thing that changes is who, or what, is making the rules.

Distributors and marketeers now openly recommend it as a way to maintain visibility, especially for emerging artists. And in our social media era, it fits hand-in-glove.

So yes, I understand why it exists. The industry is crowded, attention is fleeting. If you can stretch your album into five or six “mini-campaigns” instead of one, why wouldn’t you? You’re playing your cards slowly, one by one, taking up as much space on feeds and streaming playlists as you can.

But here’s where I take issue: in practice, I think waterfalling often does more harm than good. That is unless it’s baked into the creative vision from the start.

The problem is that most waterfall albums weren’t designed to be experienced in fragments. They were conceived as a single body of work. The tracks are thematically, emotionally and sonically connected. And when you break that apart and scatter it across months of drip releases, to me it feels like you’re diluting the impact. By the time the full project is finally out, the early singles feel old now, the momentum is no longer there, the connective tissue between them has thinned to almost nothing and the audience’s emotional connection to the music has frayed.

Social media only compounds this. Our feeds move fast. People don’t have the mental bandwidth to constantly connect that that track from two months ago is part of that album that’s still not fully out yet. Instead of giving the album its own big moment, you risk making it background noise, another piece of content among countless others.

But I will say that at the same time, people’s attention spans are shrinking, and maybe there is a benefit, to consume it slowly in small doses, rather than trying to find the time and space in our crowded world to listen to a whole project all at once. It seems like releasing music nowadays always involves some kind of tango with our mental and emotional bandwidths. Between infinite scrolling, constant notifications, and the sheer abundance of content, finding an uninterrupted hour to sit with a full album is, for many people, almost a luxury.

In that context, waterfalling might not just be a cynical algorithm play. It can be an act of pragmatism, even accessibility.

There’s also something to be said for the way a slower drip of releases allows songs to breathe. In a traditional album drop, weaker tracks can get buried, overshadowed by the lead singles or skipped entirely. Waterfalling can give every track a moment in the sun, encouraging deeper listening and more intentional engagement.

In a way, this isn’t so different from serialized storytelling. Think of how TV shows like Succession or The Last of Us build cultural momentum through weekly episodes, allowing audiences to discuss, process, and anticipate. Similarly, staggered music releases can create space for reflection, discussion, and repeat listens before moving on.

That said, there’s a tension here. What’s meant to be slow and mindful consumption can easily slide into a form of cultural fast food, where the slow pace isn’t necessarily about savouring, but about stretching marketing cycles. The same structure that allows space for appreciation can also strip away the immersive world-building that makes albums powerful in the first place.

In other words: waterfalling can be a thoughtful adaptation to our overloaded minds, if the pacing is in service of the listener’s experience, not just the appetite of the algorithm.

And waterfalling can work beautifully when it’s intentional: when each track has its own narrative purpose, when the staggered release builds genuine suspense, when the music itself actually benefits from being unfolded slowly. But too often, it’s not an artistic choice but a marketing reflex. A symptom of the same logic that tells artists to post every day, to always have something new, to never go quiet or risk invisibility.

And that’s the delusion: the idea that stretching things out automatically means taking up more meaningful space. In reality, you may just be thinning out your own impact, trading a single strong wave for a series of small ripples.

The rise of waterfalling is part of a larger shift in how we experience music. We no longer gather for an album drop the way we once did. We no longer sit with a body of work in its entirety before the discourse moves on. Instead, we consume it in pieces, often without realizing the whole has even arrived.

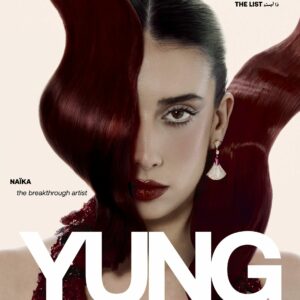

For more on the latest music coming out of the MENA region, visit our dedicated pages and follow us on Instagram.