By Link

By Link

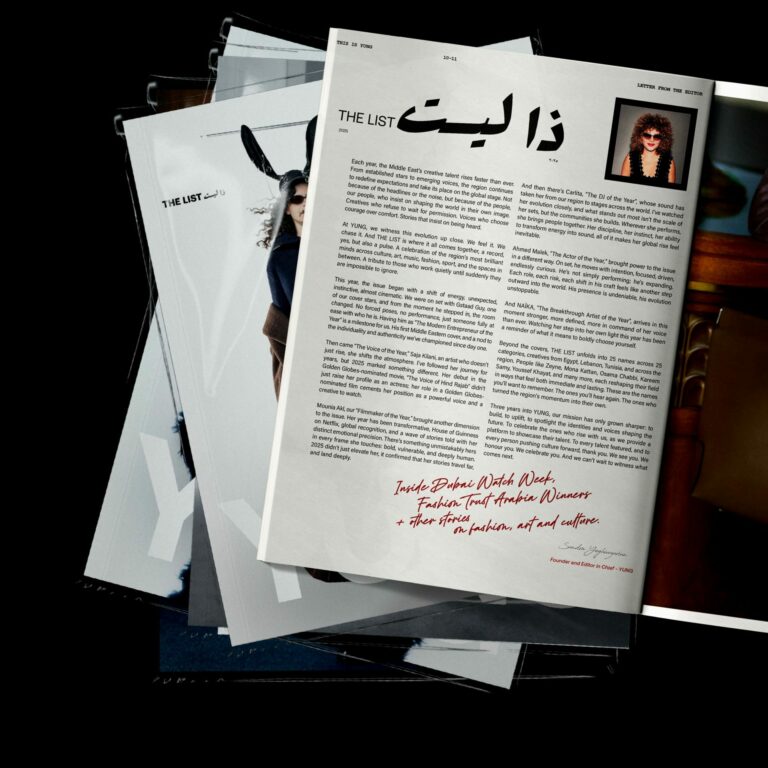

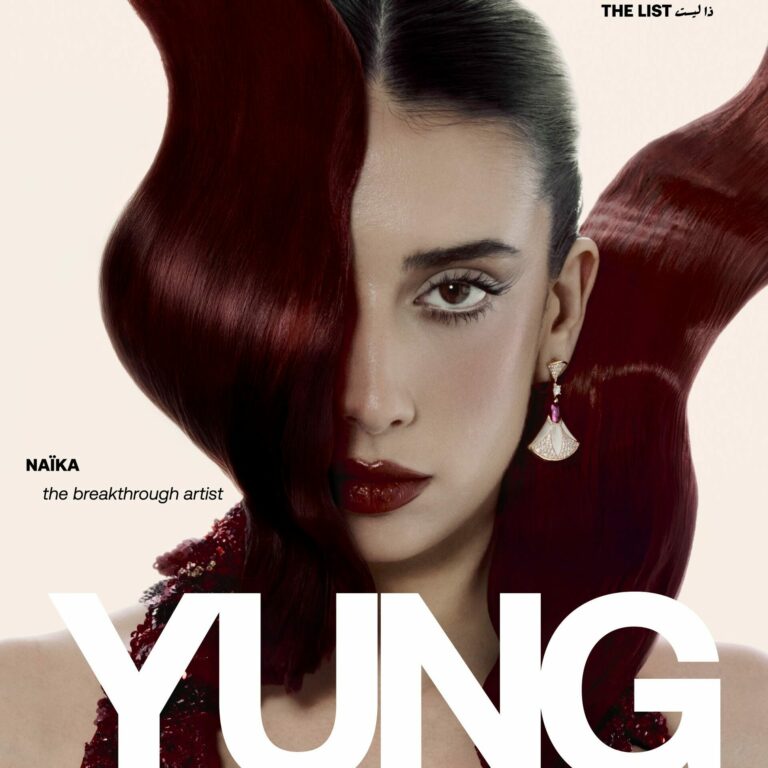

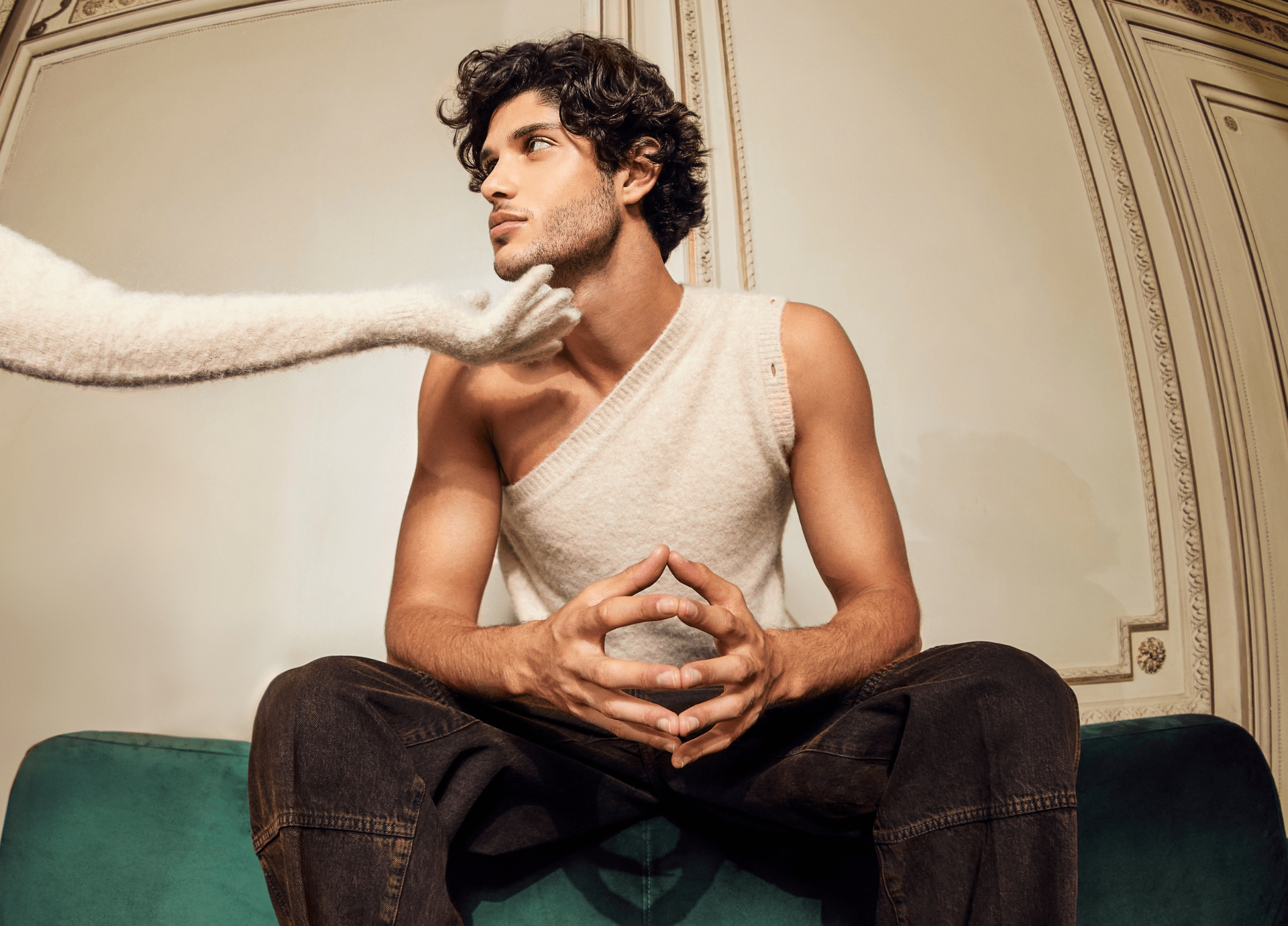

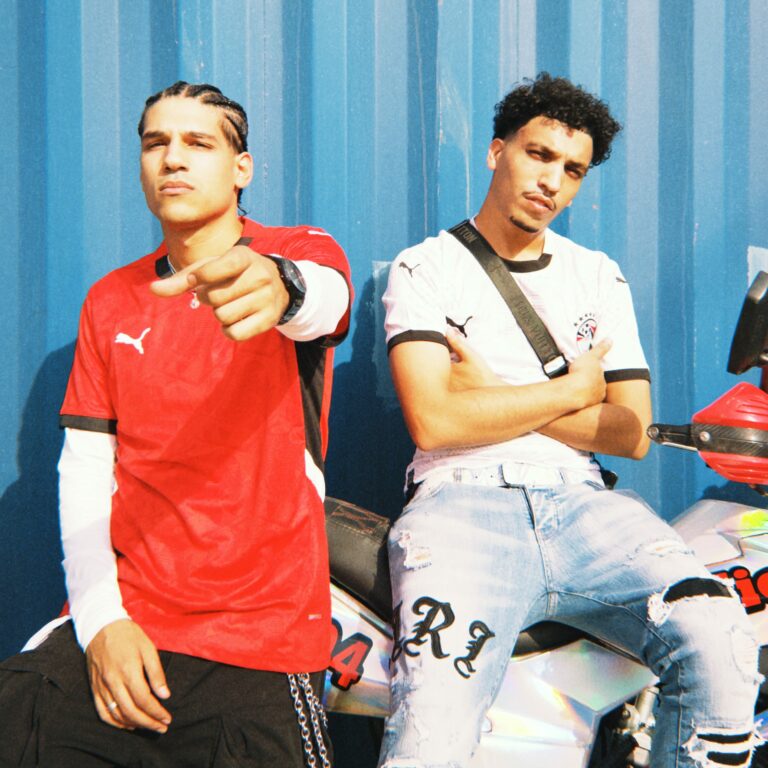

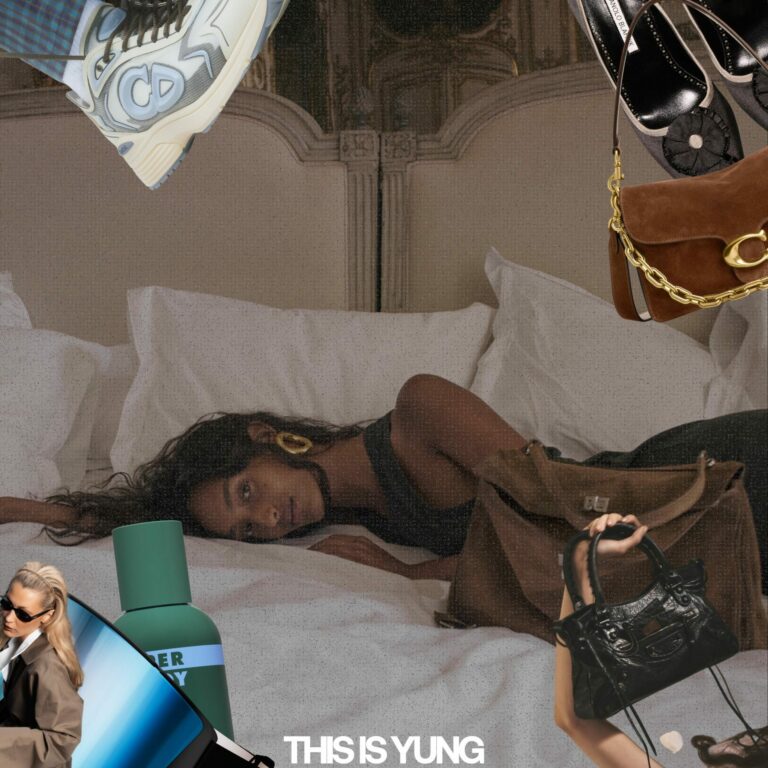

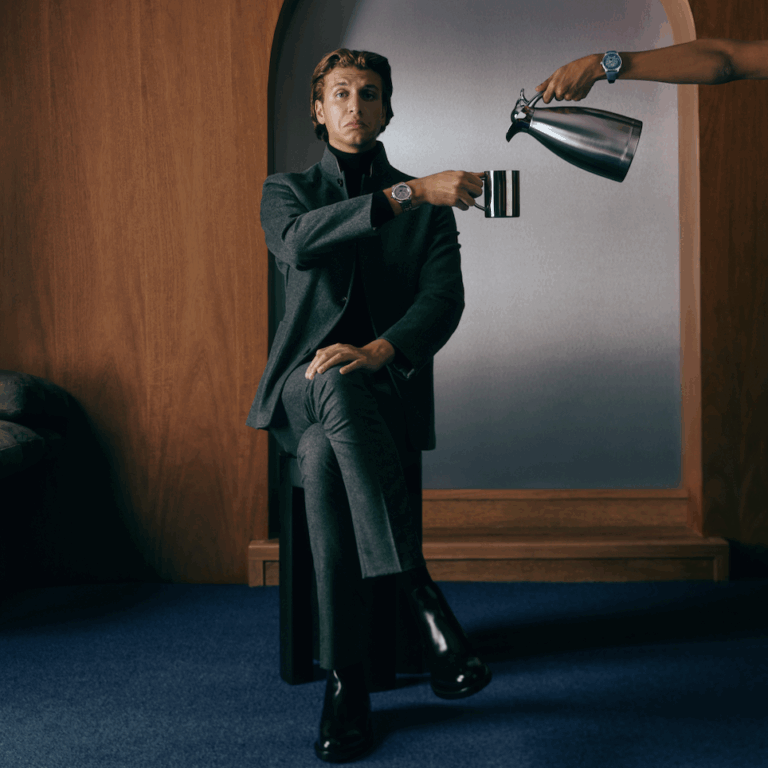

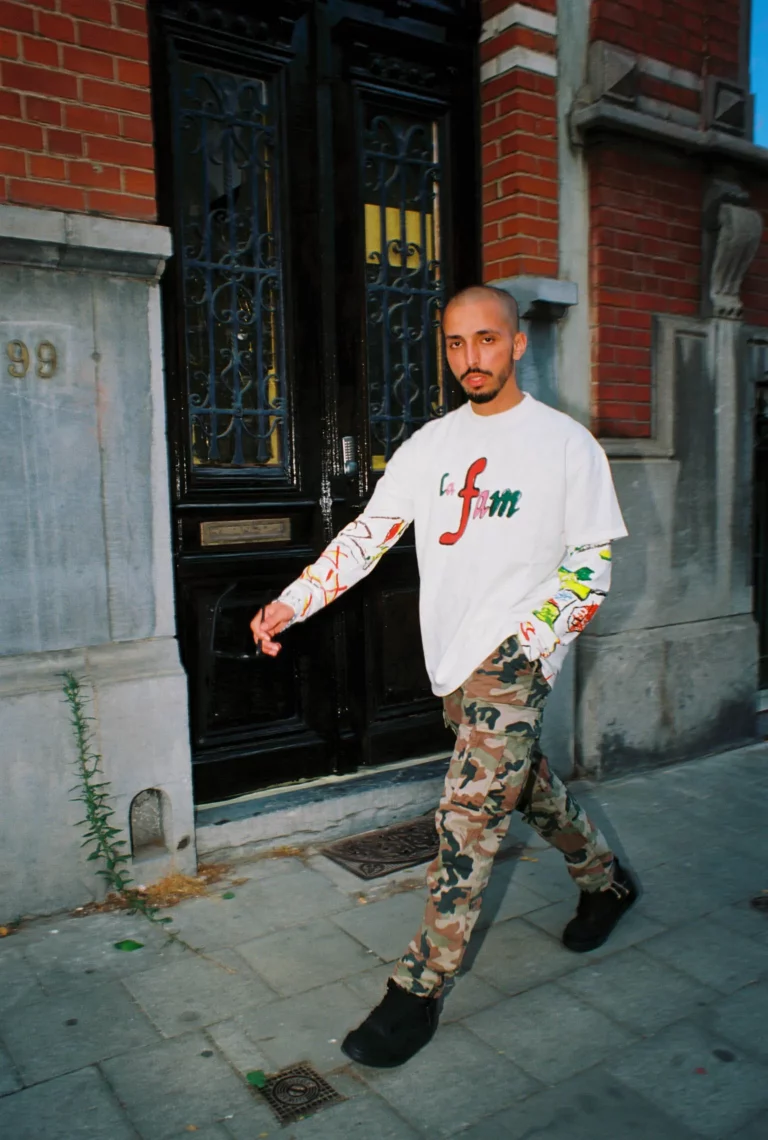

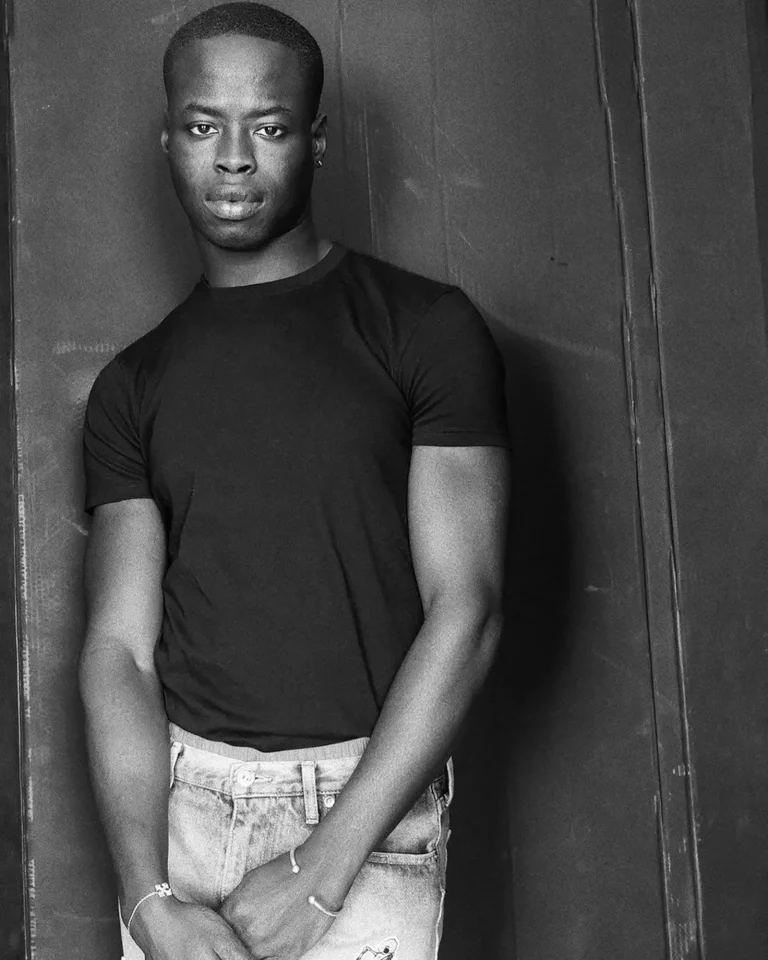

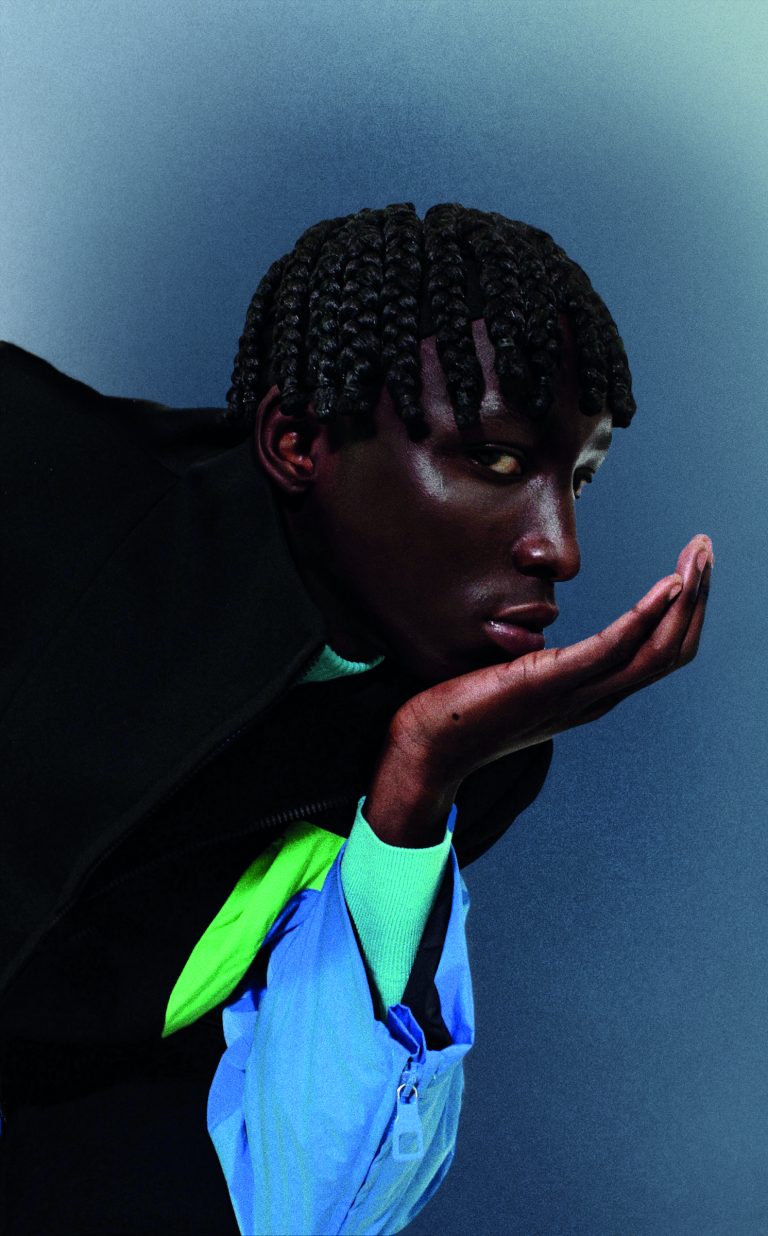

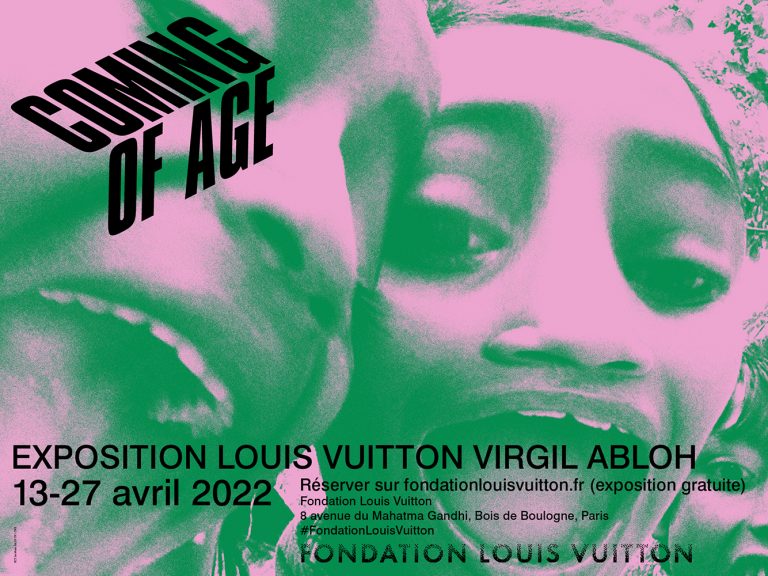

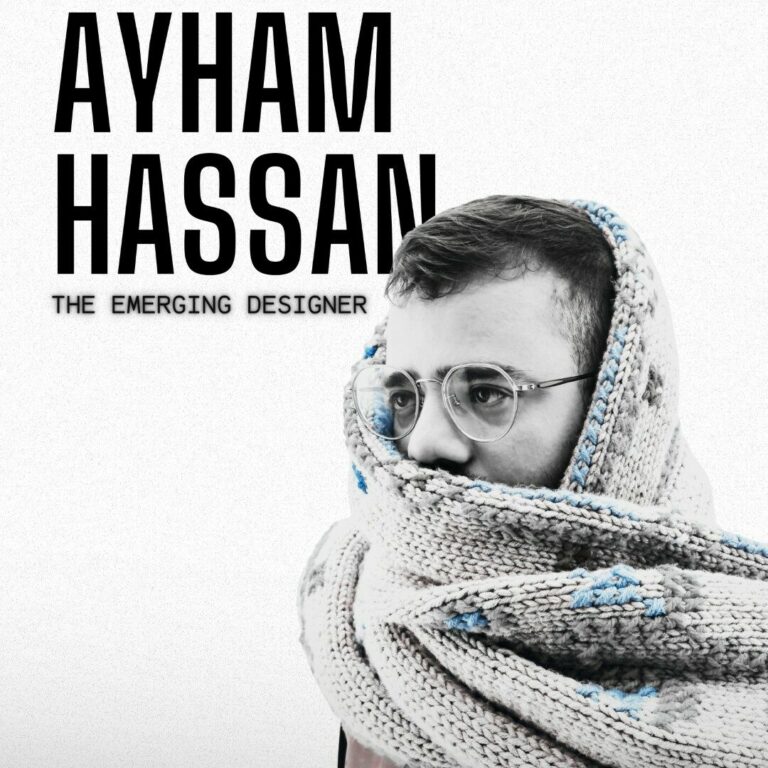

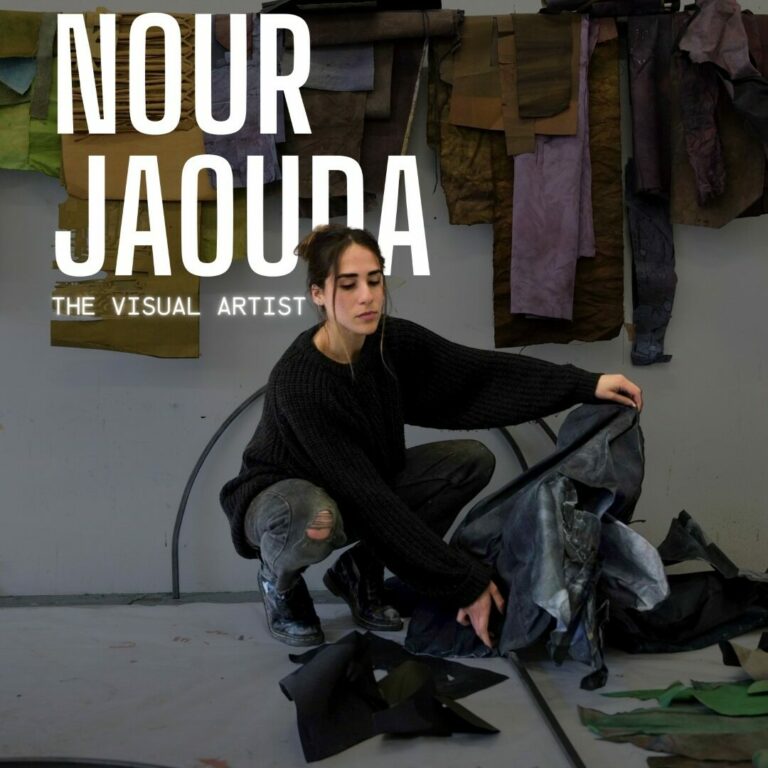

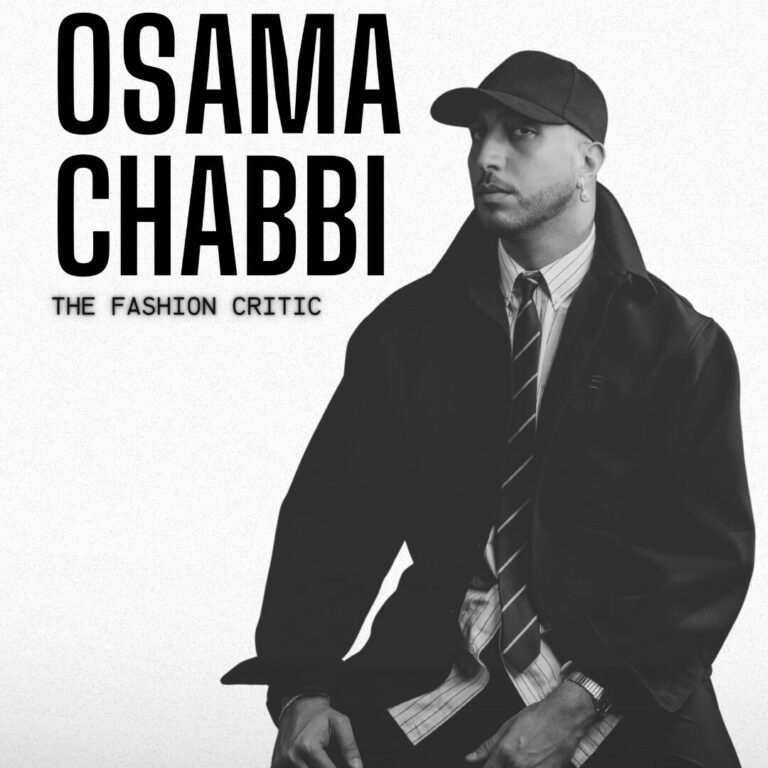

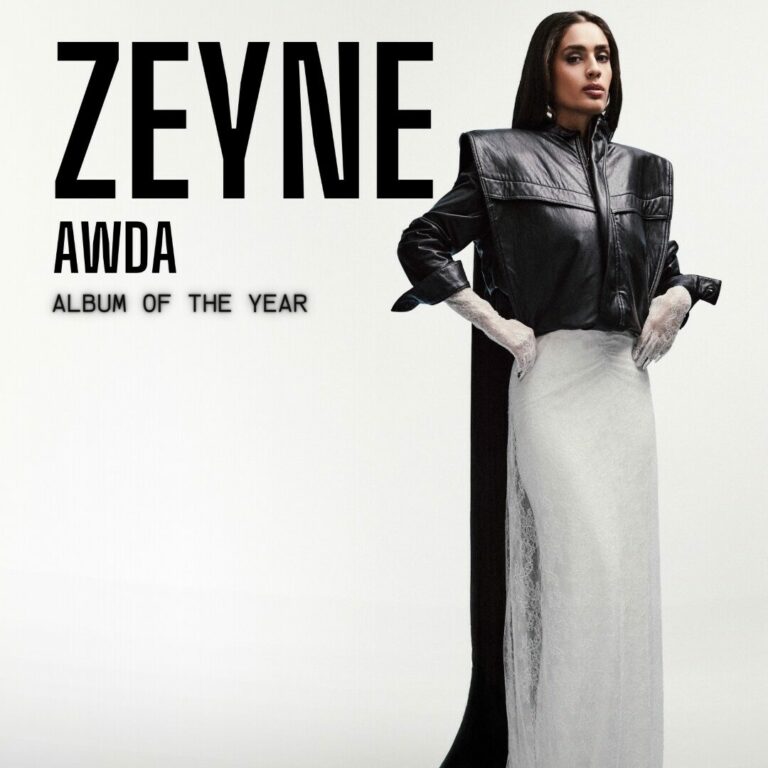

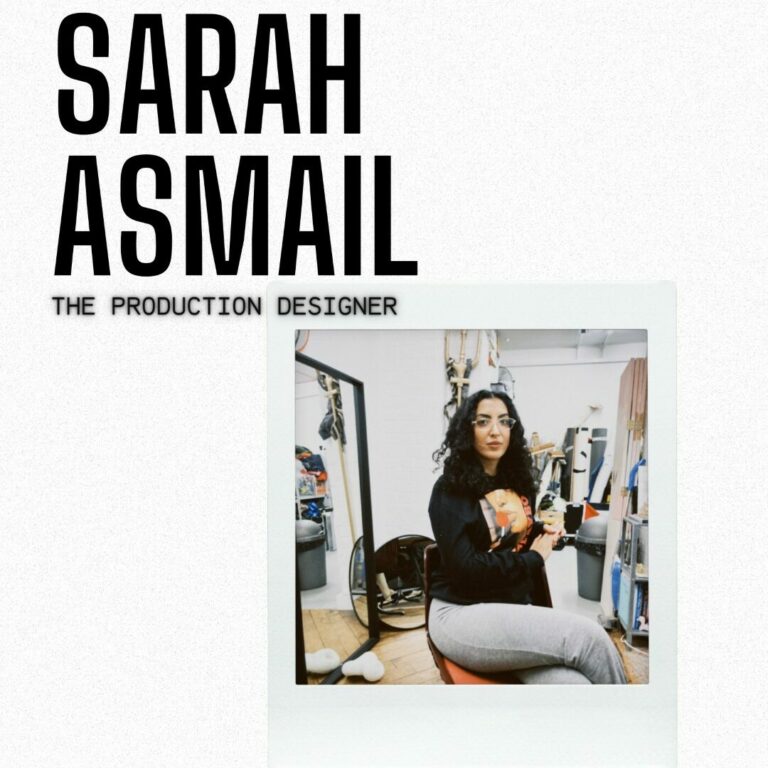

"YUNG is a quarterly magazine and online platform in the Middle East and Africa celebrating global art, fashion, music and culture. Designed to empower the next generation, this project is born to exhibit remarkable talent from these regions."