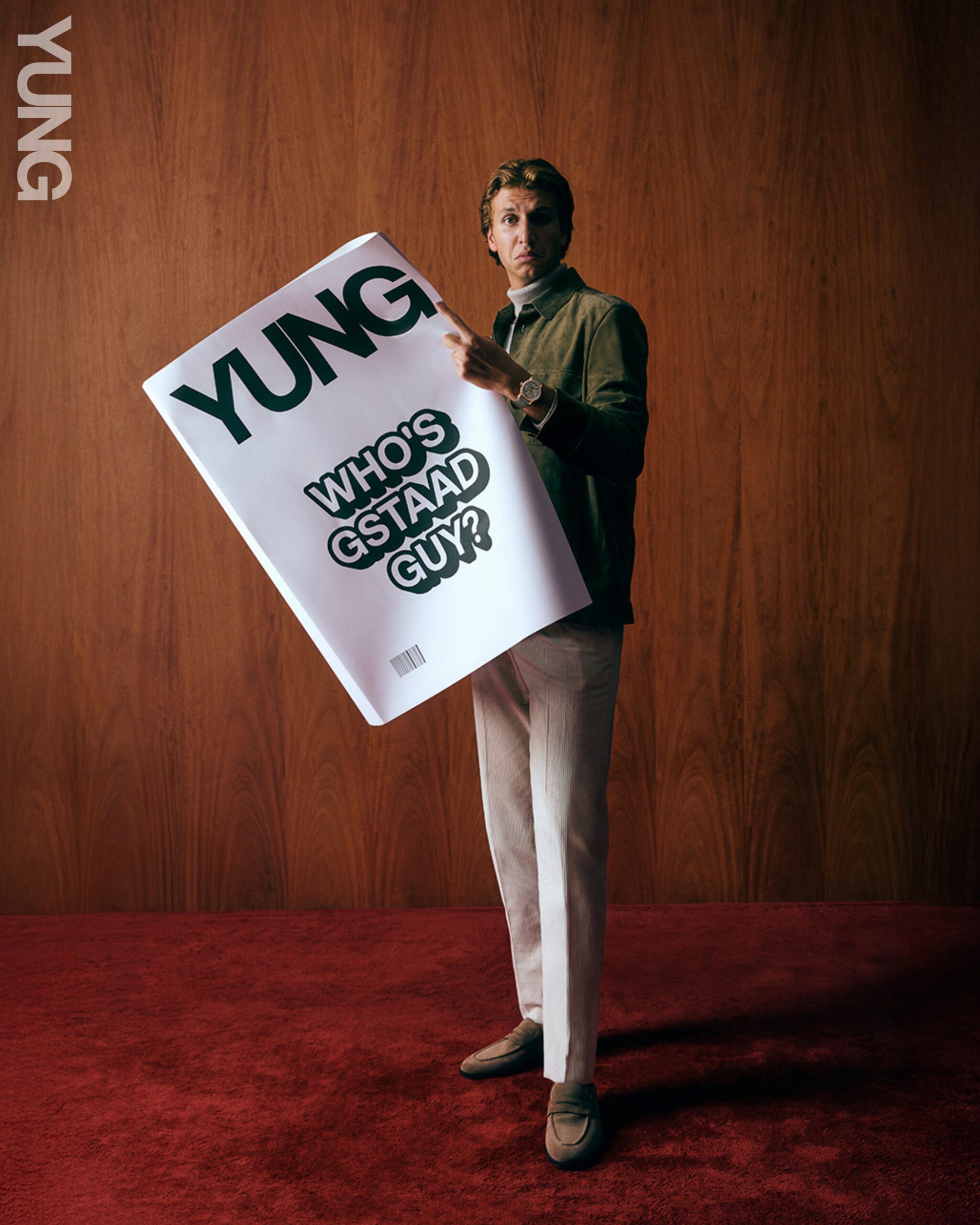

We turn on the camera, a Dubai-London connection. He’s quite demure, disarmingly calm – composed, polite, friendly – with the ease of someone who knows exactly how they’re perceived, and how to play with that perception. For a few years now, Gstaad Guy (Instagram) has existed somewhere between satire and aspiration, the performance of modern wealth. Yet in conversation, the edges blur, he speaks with the same precision he performs with, careful, deliberate, premeditated in the way he builds a sentence. He speaks about luxury the way an architect might describe light, as a material, a vocabulary, a means of shaping experience.

When Gstaad Guy first appeared online, he was a caricature of privilege: the exaggerated embodiment of an upper-crust archetype so absurd it could only have been invented by someone who understood its codes intimately. The satire was sharp, the accent impossible to place, and the humour layered with just enough self-awareness to make you laugh with him rather than at him. What began as a parody of abundance quickly became a mirror for it. “The growth was intentional,” he says later, “but the path was consequential.”

What’s striking in retrospect is that there was always a clear north star – humour, excellence, and self-awareness – these three principles have been his engine, the reason a parody became a philosophy. The humour is absurd, yes, but never careless. The aesthetic, exacting but never self-serious. And the self-awareness? It’s the connective tissue that allows it all to hold. The comedy may have hooked viewers, but the precision – in tone, editing, and observation, revealed someone deeply serious about craft. “Luxury, taste and connoisseurship,” he says, “were always going to be part of the shtick – and they still are.”

That consistency of values explains how a fictional character became a cultural platform. The Gstaad Guy universe evolved from 60-second skits into a podcast supported by legacy brands, a jewellery line built on inside jokes, and a global community fluent in irony and discernment. Seven years later, Gstaad Guy stands as a case study in how internet satire, when anchored in taste and intellect, can become both brand and mirror: a commentary on modern luxury, and an increasingly essential part of it.

Gstaad Guy recently launched his own podcast, realizing that the short-form satire that once poked fun at modern privilege had become too small for the ideas and experiences he wanted to explore. “Sometimes I experience beautiful things,” he says, “and I feel guilty that I’m experiencing them alone.” The podcast was born from that “guilt”, from a desire to share the kinds of conversations that once stayed private, the moments of connection, intellect, and curiosity that don’t translate into 60-second bites.

Gstaad Guy speaks of beauty the way he speaks of luxury: as something to be observed, contextualised, and shared. The podcast, in that sense, became his antidote to the solipsism of internet fame. Part of the appeal, he admits, was the resistance to scroll culture. “Every few months, people’s attention spans are nearly halving,” he says. “When they’re scrolling, they skip past almost everything.” Long-form audio, by contrast, demands presence. “If someone chooses to listen for an hour, they’re opting in. They’re invested.” The distinction matters to him.

What’s striking is how much of himself he allows into this new format. Gone is the exaggerated accent, the ironic detachment. Friends had long told him to “break character,” but it wasn’t until he appeared as himself on Logan Paul’s ‘Impaulsive’ podcast that he realised people wanted to see that version of him “The real me isn’t actually very comedic,” he admits. “I’m just attentive. Curious.”

And that curiosity has become the through-line. Whether he’s speaking to an influencer, a CEO, or an artist, what he’s really probing is the why and the how behind excellence. His best guests, he says, are those who can talk about “something greater than themselves,” who leave listeners with more questions than answers.

As his audience expanded, so did the world he built. “Luxury is unnecessary,” he says. “But it can be beautiful.” His collaborations aren’t about mocking the system from the outside; they’re about exposing its human texture from within. “People forget brands are run by people,” he adds. “And those people have a sense of humour.” If his success, his humour, proves anything it’s that people are still moved by beauty.

His partnership with Audemars Piguet is an extension of his central thesis, that taste and excess, beauty and absurdity, can coexist. Working with the brand deepened his fascination with technical mastery, watches so thin they seem impossible, “if-you-know-you-know” objects that whisper connoisseurship. “They take their craft seriously,” he says, “but not themselves.” What draws him in most is the brand’s ability to compress staggering complexity into something discreet. He speaks of their ultra-thin models – the Royal Oak “Jumbo” in particular – with reverence, calling them “understated but still with this shine.” His favourite, the Quantum Perpetual Ultra-Thin Jumbo, embodies everything he loves: restraint with depth, precision with personality. “It’s like a multifaceted person,” he says. “True to their values, but able to adapt, elegant at a gala, relaxed at a party, and still unmistakably themselves.”

Then there’s Poubel – the inevitable next act in the Gstaad Guy universe. It began, like most things he does, as an inside joke. “À la poubel,” a phrase once thrown around in his skits to exile poor taste and bad manners, somehow became a motto, a form of cultural shorthand for his audience – a code that signalled irony and discernment in equal measure. “If two people both find humour in something absurd,” he says, “they become ten times closer.”

From that connection, a brand emerged, jewellery that functioned as both object and language, made to be worn like punctuation – discreet, witty, exquisitely crafted. Silver charms engraved with phrases from his world, little relics of shared understanding. “It was about creating something you could hide under a sleeve or show to someone who gets it,” he says. “A conversation piece, literally.”

“If saying something is good is meaningless, then the inverse should also be true,” he calls his brand “trash” to mock luxury’s obsession with self-importance. It’s Duchampian. “Every new luxury brand is trying to convince you how luxurious it is,” he says. “But that’s not for the brand to decide, it’s for the consumer.” So instead of proclaiming beauty, he chose the opposite: Poubel – French for trash. It was part provocation, part philosophy. The joke, as always, revealed the truth: that confidence and irony aren’t opposites, but allies. The pieces are finely made, hand-finished but they don’t need to insist on their worth. They exist in the same paradox as their creator: a blend of sincerity and self-awareness, beauty and wit, luxury and laughter.

Like the character that birthed it, Poubel has outgrown its punch line. It’s no longer just a commentary on excess, it’s proof that the most intelligent kind of luxury is the one that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

If there’s one thing Gstaad Guy understands, it’s how to evolve without missing the plot. Now, his focus is on keeping it that way. The projects ahead – more collaborations, a new chapter for Poubel, the continued expansion of his podcast – are not about scale for its own sake, but about preservation: of humour, of curiosity, of the sense that all of this still feels like play. “I think people sometimes assume there’s this big strategy,” he says, “but a lot of it is still just me having fun.”

That fun, however, is built on discipline and attention to detail. He remains meticulous about tone and message, cautious not to let success flatten what made the whole thing magnetic to begin with: irony with heart. As he said before, “Luxury is unnecessary, but it can be beautiful.” The same could be said of the world he’s built: unnecessary, perhaps, but beautiful in its absurd precision.

When asked about the future, he resists the temptation to over-intellectualise it. The mission, as he sees it, is to stay light. “It’s not that deep,” he says with a smile. “I’m just having fun.”

And maybe that’s the secret, why, after seven years, the character, the creator, and the commentary still work. Because in a world desperate to define itself, Gstaad Guy reminds us that taste, like humour, only really lives when it breathes.