As Valentine’s Day approaches, I’m reminded of the phrase, “In our countries, love walks on tiptoe.” This is what Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani once said about love in the Arab world. In his eyes, it is a life lived in the margins; every gesture is a negotiation between desire and the eyes of an all-too-watchful world.

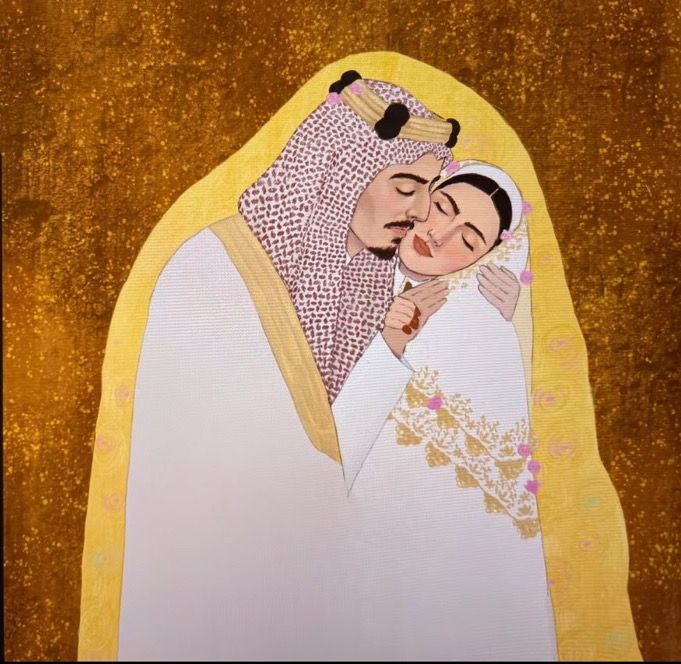

Love, in much of the Arab world, has rarely been loud. It has lived in glances held a second too long, in letters folded and hidden and stamped with hot wax, in phone calls cut short at the sound of footsteps. It has existed in carefully chosen meeting points — coffee shops far from family neighbourhoods, parked down streets where you wouldn’t “accidentally” be seen, timing that had to be perfect or not at all. This perpetual holding back turns the most natural human connection into a series of strategic manoeuvres, navigating a landscape where public judgment is the default.

This Valentine’s Day, as love appears louder, bolder, and less hidden than ever, it’s worth revisiting how secrecy has historically shaped romance across the Arab world. It would also be naïve to pretend that this secrecy has disappeared. Class and history still dictate the rhythm of the heart, carving boundaries where there should be none. In 2026, love has not been liberated; it has simply learned to hide better, surviving in the shadows of ‘discretion.’

In generations past, to love out loud was to risk everything. Affection was filtered through the rigid sieves of family authority. Today, we might choose privacy as a lifestyle, but for our predecessors, it was an ironclad requirement. In the MENA region, it’s the very framework through which we understand romance.

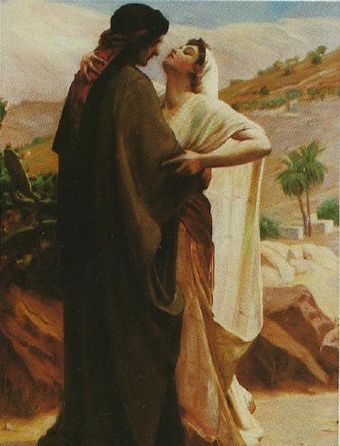

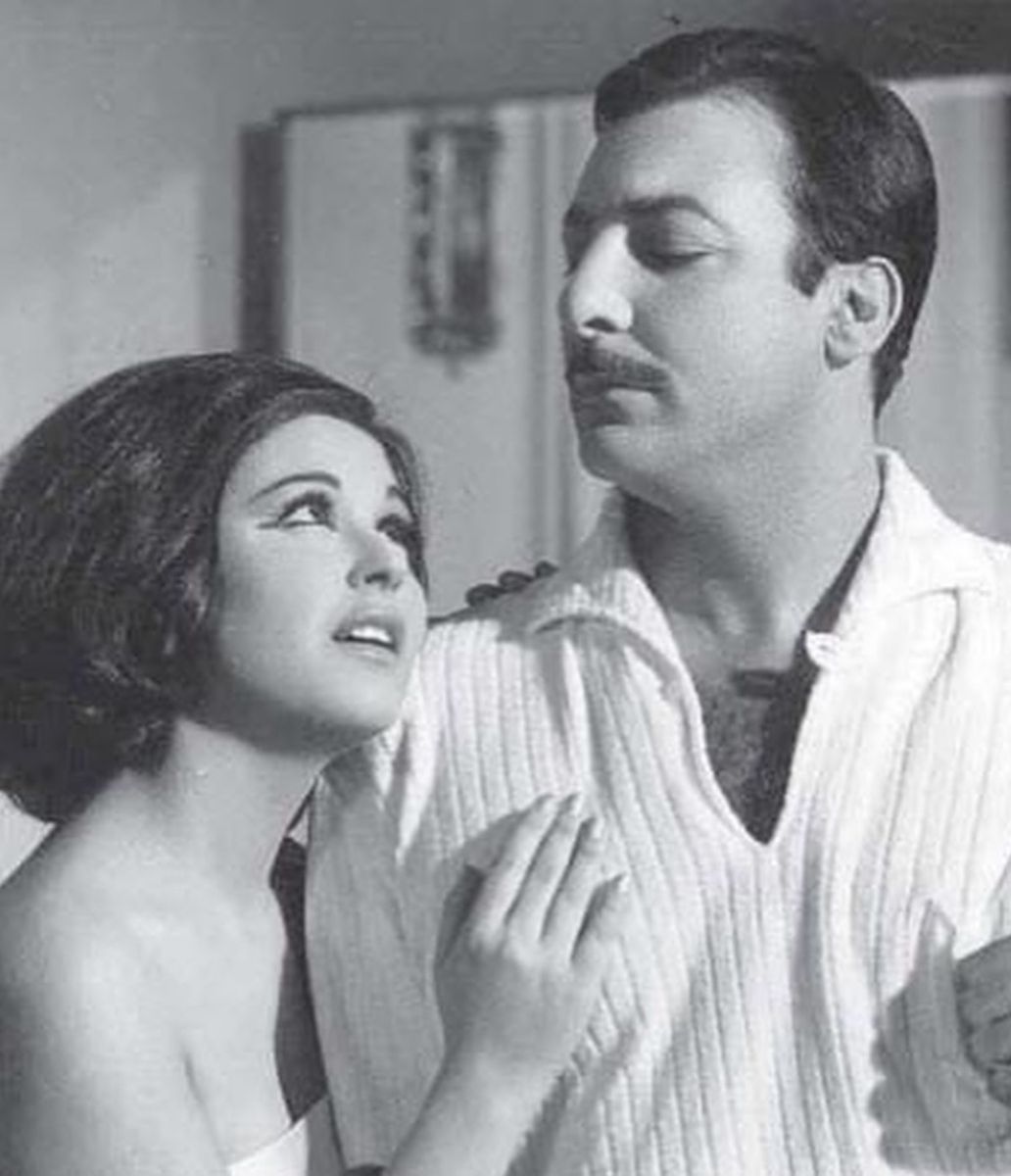

In the mid-century cinema of Egypt, love never existed in a vacuum. In fact, it was forged in the heat of friction. Romance was a battle against the era’s heavy pillars: parental edicts, stagnant class hierarchies, and the constant, crushing weight of financial ruin. In this Golden Age, lovers were relegated to the shadows, and confessions were whispered at the edge of tragedy. Happiness was a hard-won reprieve—if it arrived at all.

In Doaa Al-Karawan (The Nightingale’s Prayer), love is inextricably bound to the brutal trifecta of violence, honour, and blood. Faten Hamama’s Amna is born from the ashes of an ‘honour killing’, her sister’s life extinguished by an uncle’s hand. Amna embarks on a mission of vengeance that curdles into an impossible love. It is a cruel irony: she falls for the very architect of her family’s ruin. That love almost costs her her life, too. In this world, desire is a predatory force.

On the other hand, in Al Wesada Al-Khalia (The Empty Pillow), intimacy is a casualty of social mobility. Salah’s first love isn’t destroyed by a single blow, but by the slow erosion of class and financial pragmatism. When Samiha chooses the security of a wealthier suitor, Salah is left suspended in the amber of what might have been.

The iconic image of Salah clinging to his pillow and imagining Samiha’s face turns a void into a protagonist; the empty space beside him becomes more real than his actual life. It is a haunting image of the persistence of longing, proving that some loves just learn to exist in the shadows of a new reality.

Then there is Aghla Min Hayati, starring Shadia and Salah Zulfikar, a film that stretches love across decades rather than destroying it in a single blow. Two young lovers are separated not by death or betrayal, but by paternal authority. Her father refuses the marriage, and the relationship collapses under obedience and circumstance.

She remains unmarried, suspended in the ‘what if’. He moves forward, marries another woman, and builds the life expected of him. Years later, when they are older, their reunion is charged with the ghost of a dormant passion. Inevitably, they marry quietly behind everyone’s backs, almost clandestinely. Even after time has stripped them of their youth, the habit of discretion remains, turning their long-awaited union into a whispered secret.

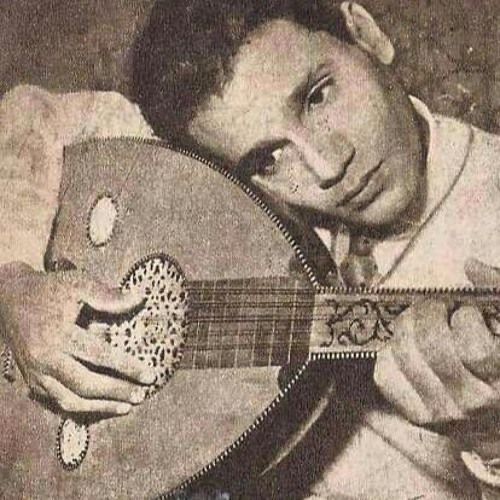

These films are studies in the art of the unsaid. In this cinematic landscape, desire lived in the implication; a single glance across a crowded room carried a more devastating weight than a kiss ever could. The music of the era echoed this same emotional architecture. Lyrics dwelled in the agonizing space of shawq (longing) and intizar (anticipation). To love was to wait. To miss.

Um Kalthoum’s Enta Omry captures the specific ache of love that arrives out of sync with time. While rendered as ‘You Are My Life,’ the title possesses a gravity that standard English cannot pivot. Anchored in Maqam Sikah Balady, a melodic mode synonymous with profound tenderness, the composition unfurls with a delicate intimacy that gradually surrenders to desperation. This specific mode is known for its quarter-tones, which create that “in-between” sound. It literally sounds like a voice caught between a smile and a sob, which mirrors the joy and grief blurring into one.

Over the course of an hour, the song navigates the wreckage of time, beginning with the haunting realization: ‘Your eyes took me back to my lost days.’ It is a meditation on the tragedy of late-arrival love, a woman discovering the sun only after a lifetime of shadows. When she sings, ‘the days before you were a waste,’ she is mourning the decades she spent waiting for a ghost, a declaration shadowed by an unspoken question: where were you all this time?

If Umm Kulthum provided the soul of yearning, Abdelhalim Hafez provided its heartbeat, whose music and films consistently framed love as a state of perpetual vigil. In classics like Ahwak, Ana Lak Ala Toul, and Gana El Hawa, devotion thrives specifically because of its distance. His films, such as Maabodat El Gamahir, Maw’ed Gharamy, and Sharea El Hob, famously suspended narrative momentum to make room for his songs. In Ana Lak Ala Toul, Hafez sings of love as both ache and surrender, “I endure the fire of your love,” and “I send you a greeting without words”.

While some dwelt in the shadows of longing (embodied by Layla Mourad in Malish Amal, a title whose literal translation, ‘I Have No Hope’), others navigated the same emotional terrain with a lighter, more defiant resolve. Shadia, in Wehiat Eineik and Maksoofa Menak, and Najat Al Saghira’s Ana Bastanak and Eyon El Hob, captured the breathless giddiness of a secret shared, turning the ‘discretion’ of the era into a playful game of connection.

Then there were the musical duets of love, created whenever two stars shared a song. When Layla Mourad and Mohamed Fawzi sang Ward el Gharam, or when Shadia and Abdelhalim Hafez shared the playful, cycle-of-flirtation energy of Haga Ghariba, the narrative friction briefly dissolved. In Haga Ghariba, the ‘strangeness’ they sing of is the sudden, dizzying lightness of being in sync. These songs were ‘micro-utopias.’ For four minutes, the class divisions and family edicts that policed their characters were suspended.

Fairuz, meanwhile, elevated devotion into a quiet, sacred vigil; in Sabah Wu Masaa, love is found in the simple, patient act of staying awake for another. Then there was Sabah, who pushed the stakes to their limit in Yana Yana, dramatizing surrender as a life-or-death commitment. Their artists reframed love as a risk worth taking, an invitation to live fully despite the watchful eyes of the world.

But if they provided the courage to love, Nizar Qabbani provided the tragic logic that governed its end. ‘Qariat al-Finjan’, he centres on the tragedy of the inevitable; a romance foretold to end in wreckage, yet pursued with a desperate, kamikaze devotion. In contrast, poems like ‘Uhibbuki’ (I Love You) function as a rhythmic obsession, as if the sheer repetition of the word could dissolve the walls of distance and social impossibility. Even in his most audacious verses, Qabbani never escapes the gravity of consequence; he writes with the acute awareness that to love out loud is, in itself, a revolutionary act.

In the literary world of Naguib Mahfouz, particularly in Palace Walk, love is a restricted currency, never free and rarely uncomplicated. For women especially, desire exists in the narrow gaps between surveillance and authority. Here, romance is not an open experience but a condition to be endured, shaped by the iron grip of patriarchal control and the fragile sanctity of reputation.

In this setting, waiting is a daily discipline. We see it in the hushed manoeuvres of his characters: the neighbourly love conducted ‘behind the family’s back,’ or the daughter whose potential suitor is reduced to a glimpse through the window shutters, their entire courtship mediated by the wooden slats of the mashrabiya. From behind the window, they watch the world without ever being seen.

The gendered tax on intimacy in the MENA region was, and often remains, extortionate. For women, to love openly was to gamble with safety, reputation, and life itself. Desire carried consequences that were unevenly distributed, policed through honour, family authority, and social exile. Women learned to love quietly not because silence was romantic, but because it was protective.

These dynamics were never a monolith. Geography, class, and access have always acted as the silent arbiters of who could afford to bend the rules, and who was broken by them. Urban elites navigated secrecy with a sophistication that rural communities could not; wealth functioned as a shock absorber for scandals that would otherwise be lethal.

Even in 2026, visibility remains the luxury of the few. For many, privacy isn’t a lifestyle choice; it is an existential requirement. While some romances have migrated to the light of the digital public square, others remain trapped in the margins. The language of love has evolved, but the scaffolding of the old world has simply learned to camouflage itself.

When a society spends centuries policing the heart through class and gender, the internal compass inevitably shifts. This created a cultural blueprint where suffering is the only proof of pulse. If love isn’t difficult, we question if it’s real. The collective myths range between: distance is devotion and sacrifice are the only true measure of sincerity. But today, it’s a poetic trap. It suggests that pain isn’t just a side effect of love, but its primary evidence.

This is why our stories are obsessed with the ‘impossible’; the missed connection, the stifled cry, the passionate reunion. In this loop, stability and safety become unromantic. For generations, young people inherited the idea that love must be difficult to be real. That longing is more meaningful than peace. That being seen too clearly somehow cheapens emotion.

Modern romance in the Arab world exists in the glitchy space between the public and the private (public online, private offline). However, we are beginning to interrogate the myths we were fed: Why is pain still the only currency we trust? Why is ‘patience’ glorified over presence, and why must love be a gauntlet before it’s allowed to be a home?

The art born from this restraint is undeniably some of the most visceral in the world. Secrecy, when forced upon the heart, has a way of sharpening the senses; it makes every glance precise and every word a weight. But there is a difference between appreciating the beauty of a ruin and choosing to live inside it. We can honour the songs of the past without feeling obligated to repeat their tragedies.

For more stories of art and culture from across the region, visit our dedicated archives and follow us on Instagram.