Acting didn’t come to Ahmed Malek as a career choice, it arrived long before he had the language to name it. Long before the festivals, the international scripts, the Gouna red carpets, there was a boy in Cairo flipping a dining- room table into a stage, putting on puppet shows for his family, insisting that stories were worth telling even when no one asked.

At eight years old, he walked into the industry by coincidence. At 17, he chose it, fully aware this time. Somewhere between those years, acting stopped being something happening to him and became something he was building: frame by frame, instinct by instinct, with a hunger he still doesn’t fully understand.

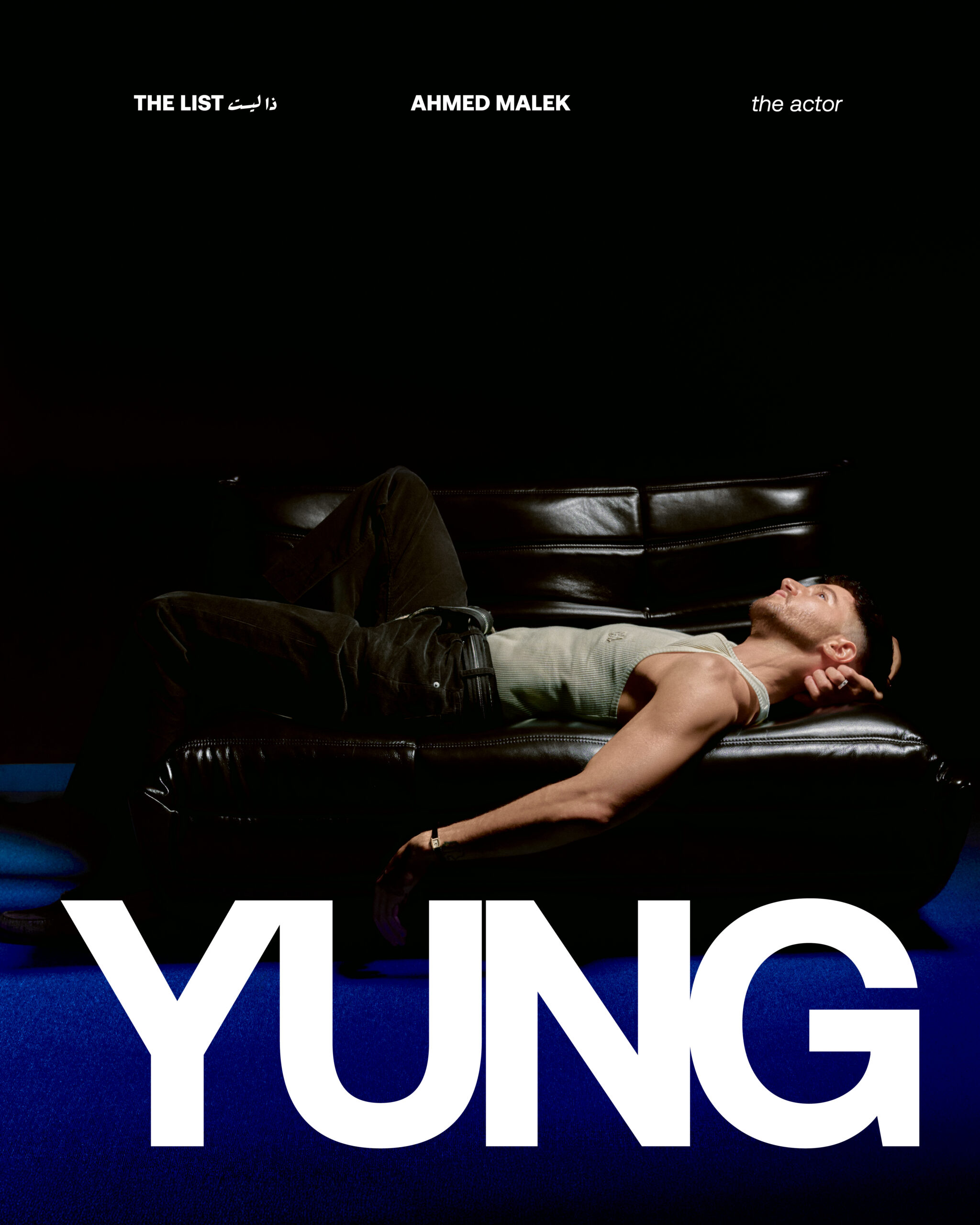

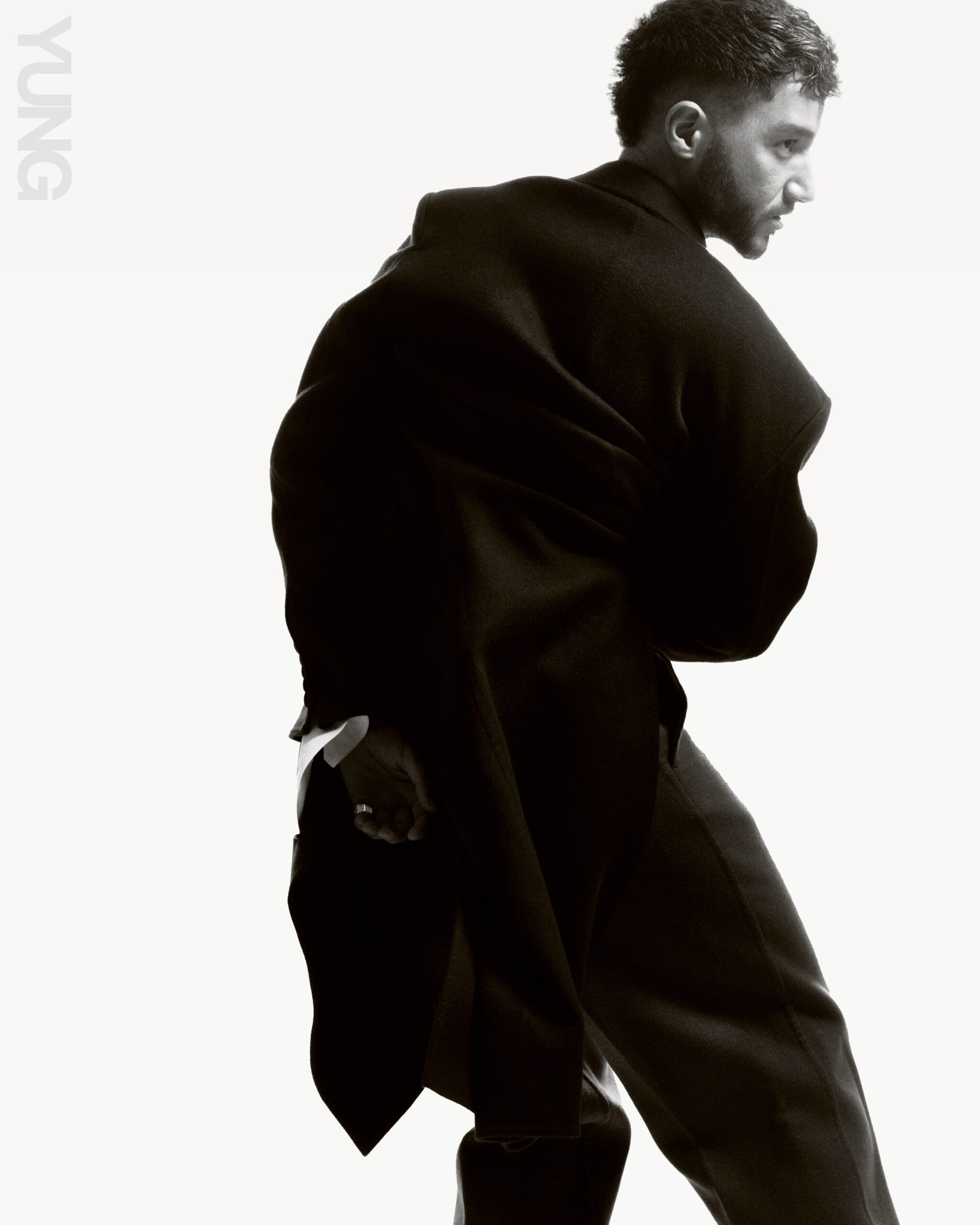

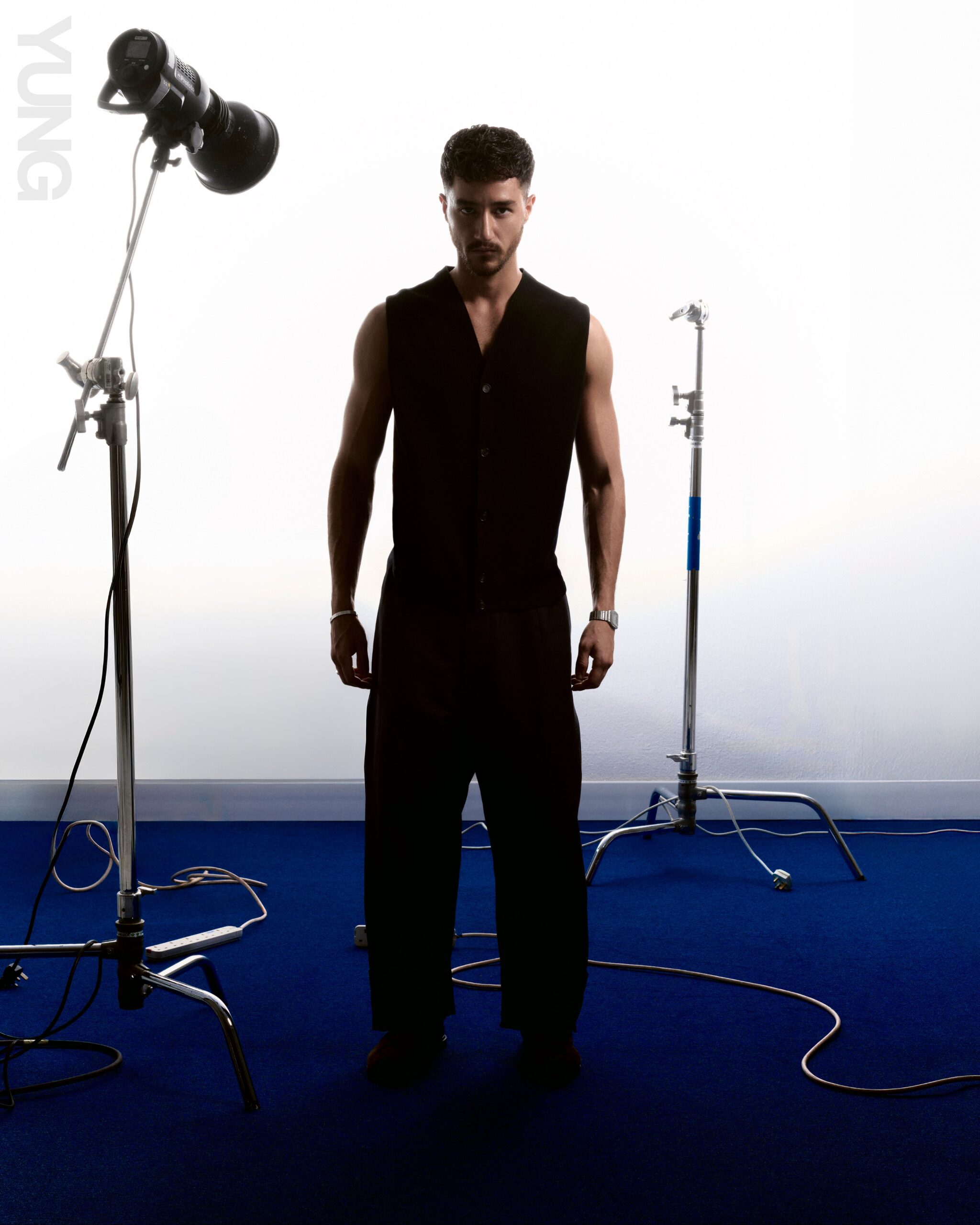

Now, with YUNG naming him Actor of the Year 2025, Malek stands at a rare crossroads: no longer the child he once was, not yet the legend he wants to become, but conscious that he’s part of a generational shift. A shift where Arab cinema has stopped orbiting Western expectations, but is turning inward; toward its own truths, its own cadences, its own unresolved questions.

You’ve said before “acting chose me.” What do you think acting saw in you that you didn’t yet see in yourself back then?

I say that because I really started so young I didn’t have the consciousness to “choose”

anything. At eight or ten years old, no one knows what they want to do in life. It came as a coincidence, and once I entered, something inside me recognised it immediately. When I was 17 or 18, at a time when people start searching for their passion, mine was already there waiting. It felt like destiny picked for me before I had the vocabulary for it. Acting became everything for me, but if I wasn’t an actor, I’d probably still end up somewhere near writing or storytelling. They’re all forms of the same instinct.

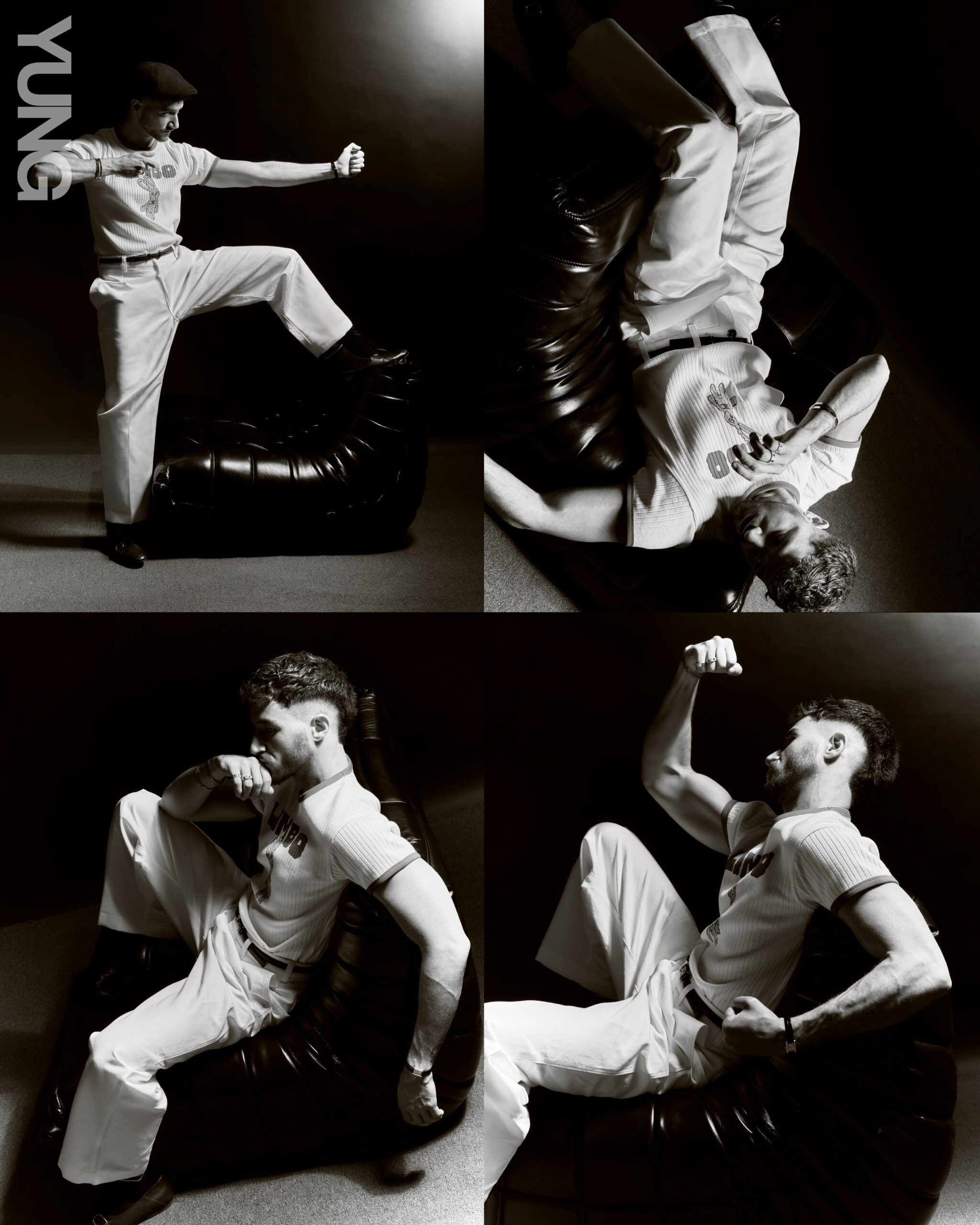

When you look at that young boy doing puppet shows for his family, what part of him still lives inside the man you are now?

The playfulness. The chaos. The kid who flipped a table into a stage at family gatherings — he’s still here, and, as an actor, he has to be.

That child is the part of me with no limits, the one who lets emotions rise without embarrassment. As you grow, maturity shapes you, and you know your tools as an actor more, but that first layer, the child, stays.

I always say Tyler the Creator’s quote: “Create like a child, edit like a scientist”. The child gives the freedom; the adult gives the clarity, the polish, and the editing.

You differentiate between being a “child actor” and a “child star.” When you look back, which would you call yourself?

A “child star” is someone famous very early. I wasn’t. I acted as a kid, yes, but people only really knew me when I was older, around 15 or 16 with El Gama’a, when I had already matured.

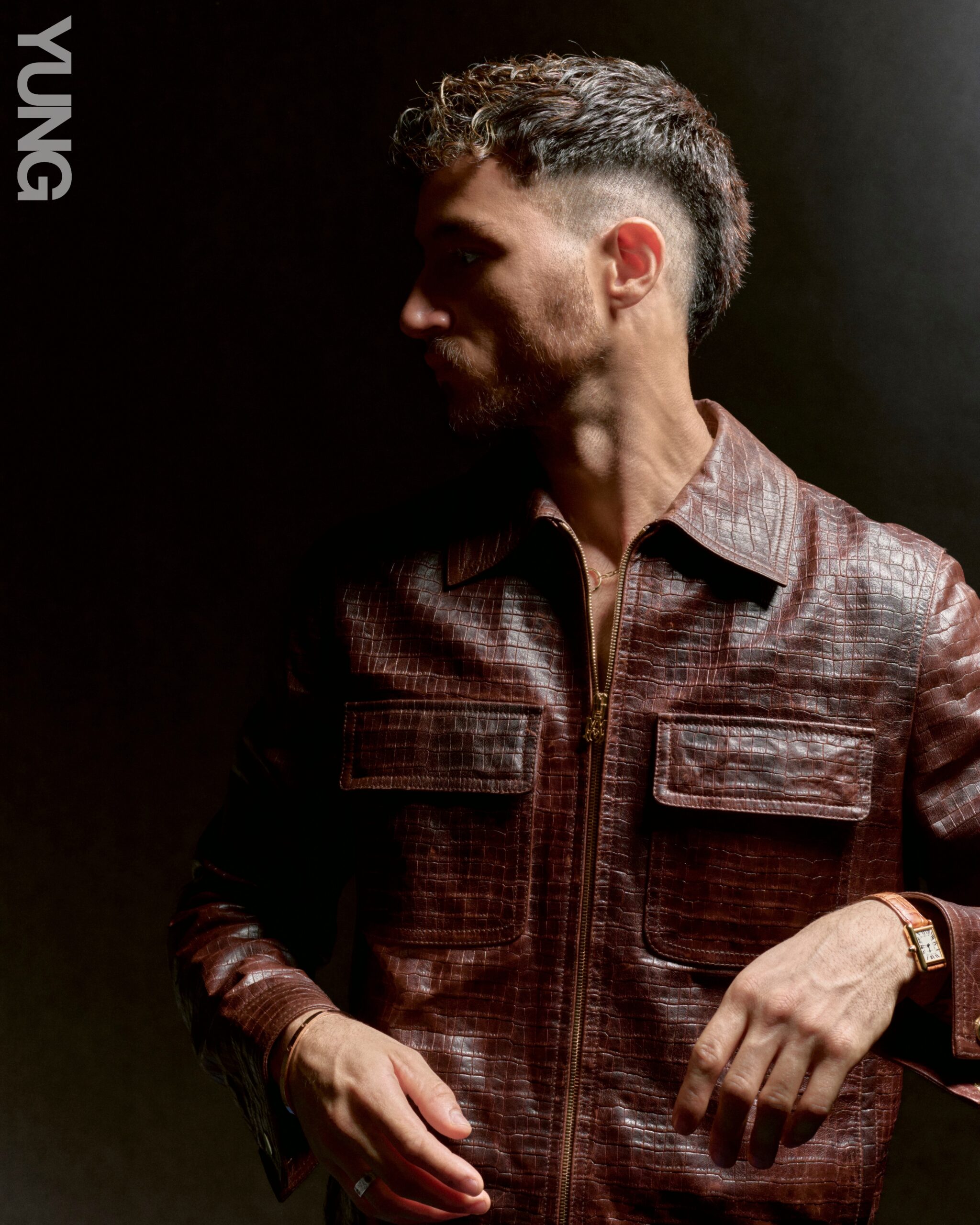

Egyptian cinema shaped you, and now you’re shaping it back. When did you first feel like you were part of a generational shift?

Honestly… this year. 2025 is one of the most important years of my life, it’s the beginning. For years, I felt like I was watching the industry from inside it: working with giants like Marwan

Hamed, Mohamed Diab, Tarek El Erian, seeing actors I grew up watching. I learned from all of them.

But this year I felt something different; that I didn’t just want to be a witness. I wanted to be an active force. To search for ideas, build teams, find directors I connect with, and contribute to Egyptian cinema’s next era.

Our cinema is historic. I want to be one of the names that carries that legacy forward. In twenty years, I want my name to stand beside the generation that raised me; Nour El Sherif, Karim Abdelaziz, Ahmed Zaki. I want the work to be real, to speak to our people, to reflect our taste as Egyptians. I want greatness, yes — but the grounded, grateful kind, the kind that earns its place.

You’ve just been named YUNG’s Actor of the Year for 2025, and received similar recognition at Gouna Film Festival. What went through your head when you heard the news? Did it change how you see your own journey so far?

It reassured me that I’m on the right path. Recognition doesn’t make me relax, though; it makes me look forward. It pushes me to think about 2026 and 2027 and how I can do better.

Robert De Niro once said that when everything feels incredible or everything feels awful, your only job is to stay steady and relaxed either way. That’s how I treat recognition — not an end point, not validation. Just a sign to keep moving.

What matters most to me is telling stories from my region, stories that feel true, without serving any external agenda. I care about my region and Arab audiences more than anything else. Our region deserves representations that resist the politics we’re living under or being branded as.

As someone whose career crosses borders, when did you realize your work could stand on its own, without looking to the West for a green light?

It comes down to two things. First off, the types of roles offered abroad. Many of them force you into stereotypes, serving a certain foreign agenda. I’m not interested in that anymore. I can’t “dance on the staircase,” like we say in Egypt. I’m not a first-generation immigrant, I don’t have that lived insight into life abroad — that’s simply not my story.

Secondly, the politics we’re living through. The region is under pressure — politically, economically. That shifted my priorities. I want my core work to speak to us. If something international aligns with my truth, I’m open to that. But I’m not running after approval from a place that doesn’t carry our weight.

Which role changed you more than you changed it?

Truly, every role changes me, and I find aspects and qualities within myself that I never even knew I had. Shakespeare says in Hamlet that acting is about holding “as ‘twere the mirror up to nature”, and vulnerability is the only way to do that. To portray someone honestly, you have to dig into yourself; your fears, your insecurities, your joy. You can’t fake it, we, as actors, have to portray the human condition. That means accessing parts of yourself you don’t always want to touch.

I’m entirely dedicated to my roles and the way I approach them, to the point that I don’t like separating who I am on-camera from who I am off it. I try to maintain those emotional qualities in both spaces, even when the camera isn’t rolling.

When I’m playing a so-called ‘bad character,’ I keep in mind that no one sees themselves as inherently evil. Everyone has motives and reasons to what they do, and in their mind, it’s justified. My work is to understand those reasons deeply enough to make them real.

My job is to make you believe, and the only way is to believe it myself first.

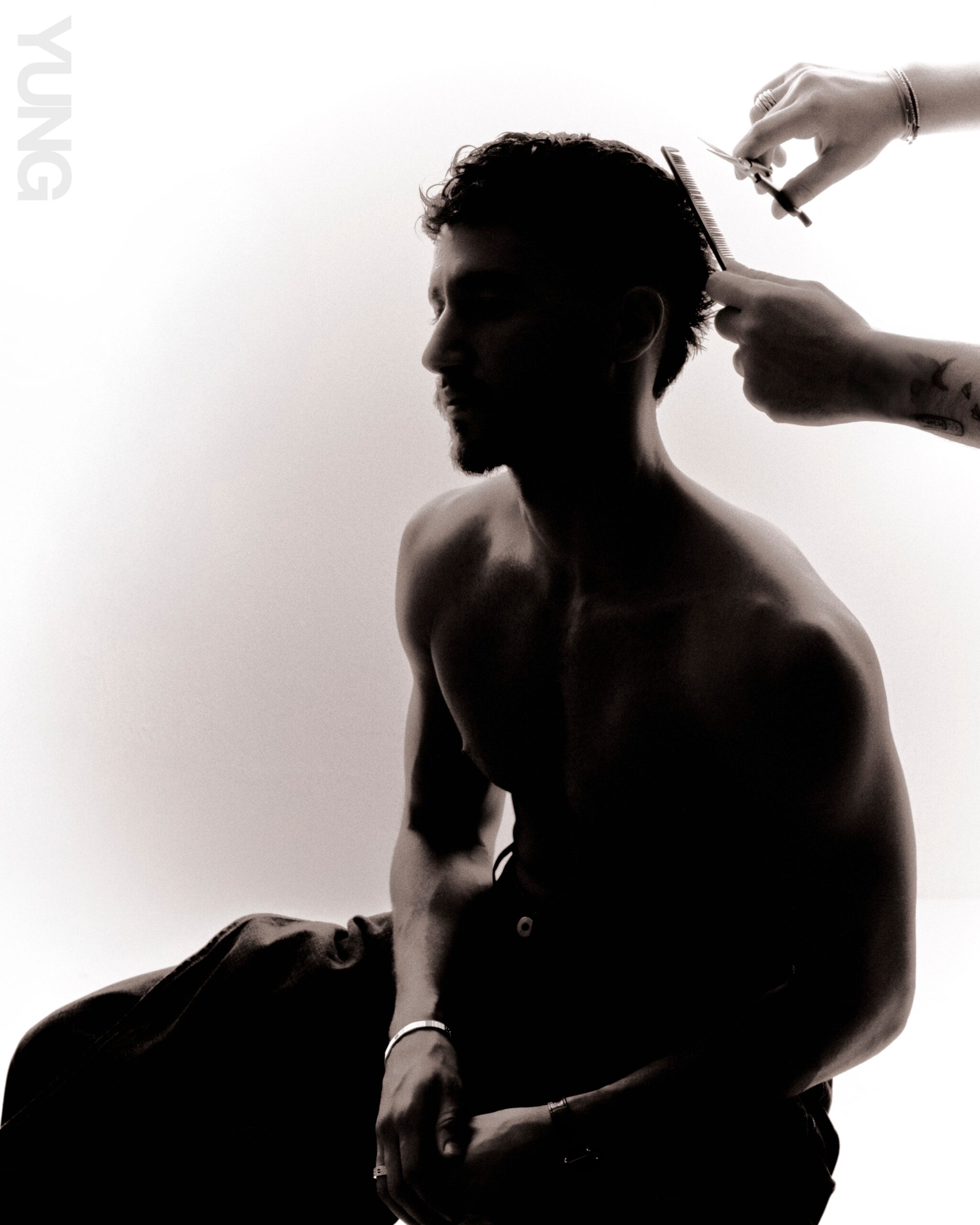

You studied at RADA (England’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts), wrote and directed your own plays. How did that change your expectations of the industry, and of yourself?

RADA changed my sense of what I’m capable of. I came back knowing I can generate work, pitch stories, develop projects, sit at a big table and contribute. When I returned from RADA, I lent a hand in developing projects like Welad El Shams, 6 Ayyam, and My Father’s Scent. I want to direct at some point. Maybe in five years… I’m tiptoeing my way in that direction.

The biggest shift was this: my voice matters, not just as an actor, but also as a storyteller. I realised people were actually connecting with what I had to say, and that pushed me to create more. My audience is the real echo chamber; it goes all the way from the people in the ahwa to the living room compounds.

I don’t want my voice to stay in one lane; rather, to reach all those different worlds. The truest

art is the kind that reaches everyone, anyone can feel it. But to speak to both the masses and the niches, I have to keep a standard of honest work, and that balance is something I’m always working on.

You’re quite intentional and particular about the stories and roles you choose. What’s the first red flag that tells you a script isn’t speaking from our reality?

When it feels alienated from our reality, or has no real impact on the Arab social fabric. The great Mahmoud Hemida once said: some philosophies we imitate from the West simply don’t fit our culture, and they show… they feel fake. If it’s not grounded in an Arab reality — socially, emotionally, politically — I won’t do it. Another red flag is when a script slips into immaturity, shallow, surface-level, almost adolescent in its thinking.

You’re drawn to stories many people look away from — the overlooked, the displaced, the lives in the margins. Why these shadows?

When I choose a role, I’m always drawn to the most human side of any character. In The Swimmers, I insisted on showing the darker, more invisible side of the refugee experience. There were countless hardships and complications refugees faced, especially early on, before anyone saw the full picture. I wanted to reflect that through my character, to show another layer of the story.

In Welad El Shams, I wanted the character to be real; strong, yes, but also flawed, sometimes insecure, sometimes harsh. The media loves to portray this fictional version of men — hyper- masculine, invincible, always tough, always ‘geda’an.’

I’m constantly trying to bring the real person instead. For my character, Wel3a, for example, I wanted to show both the shadow and the light; the contradictions, the inner fracture. A real human being.

People usually see the confidence on screen, not the turbulence that comes before it. Anyone watching your process can tell you take the work seriously, sometimes even heavily. How do you keep doubt driving you instead of derailing you?

I don’t think self-doubt ever disappears. I’m always questioning: did I really find this character’s soul? It feels like meeting someone new for the first time: what does their laugh sound like, how do they sit with their own skin? It’s part of the job to keep thinking there’s a better, truer version you can reach.

For me, doubt is fuel, but only if it’s healthy. The kind that pushes you forward, not the kind that destroys you. Before a project, I doubt everything. Once I’m on set, wearing the skin of a character, hearing “action,” I let all of it go. I have to be completely present in the moment. Doubt exists before and after. Never during.

What’s the hardest truth about acting that no one prepares you for?

One day the audience puts you on a throne. The next day they tear you down. One day they’re praising you, the next they’re throwing stones. You have to be mentally ready for both — the highs and the lows — without letting either one define you. It’s brutal, but public opinion is part of the job.

After 15 years working across genres, languages, and continents, what do you think Egyptian cinema is becoming?

I feel Egyptian cinema is in a much better place now than it was before. There’s fresh blood, new energy, real hunger. You can feel that actors have fire in them again.

Right now, I genuinely feel we’re entering a new era for Arab cinema as a whole. With major markets opening in Saudi and the UAE, the competition has risen, and suddenly we’re standing next to American films and actually competing. We’re creating cinema that expresses real life — films people on the street can relate to.

We’re finally moving away from the recycled formulas of the 2000s. ‘Siko Siko,’ ‘El Harifa,’ all these films proved loudly that we can make cinema that looks like us, speaks like us, carries our flavour, and still succeeds commercially and brings in money. That’s the direction we’re heading toward: films that feel authentically ours, and look like us.

Egyptian cinema has always been historic. Now it’s becoming contemporary again.

For more stories of art and culture from across the region, visit our dedicated archives and follow us on Instagram.