Mahraganat has always existed on the margins. Gritty. Unfiltered. Raised in the belly of Egypt’s working-class neighbourhoods with Auto-Tune vocals, clashing beats, and an attitude wrapped in defiance. It was never meant to be pretty, or palatable. And for a long time, it wasn’t even legal. The Egyptian Musicians Syndicate tried to rein it in, clean it up, or ban it entirely unless its performers met certain moral and musical “conditions.” But mahraganat refused to play nice.

Yet over the past few years, something unexpected happened. The genre that was once blamed for moral decline, banned from wedding halls, and censored on state TV is now being moulded for the global stage. Mahraganat, in all its loud, bee2a-coded glory, is suddenly edgy, hybrid, and international. It’s being sampled, stylized, and streamed by artists and audiences who used to keep it at arm’s length.

One of the latest tracks reigniting the conversation around mahraganat’s evolution is “Do You Love Me? / سنيورة,” a slick collaboration between Palestinian-French-Algerian pop artist Saint Levant (Instagram) and Egyptian mahraganat singer Fares Sokar (Instagram). The track merges Sokar’s cheeky vocal chaos with Levant’s diasporic pop sheen. It’s a far cry from the genre’s bootleg beginnings, and it’s not alone.

Saint Levant’s entry into the space is just one example of a larger shift. Just listen to “Mesh Shayfenhom” by Double Zuksh, Hassan El Shafei, and Pousi, the beat hits like something out of a club set, all tension and distortion, but the lyrics and delivery edge on shaabi. It’s a perfect example of how younger artists are playing with mahraganat’s structure without letting go of its street essence.

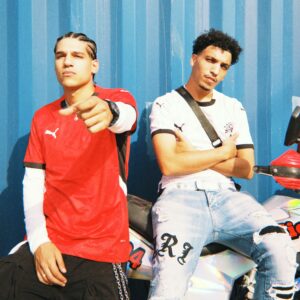

In 2022, Egyptian rap duo Double Zuksh landed an unexpected spotlight: their track “El Melouk,” a collaboration with Ahmed Saad and 3enba, was featured in the credits of the Marvel series Moon Knight. The placement marked a win for regional representation in global media, and it also led to the song charting on the Billboard World Digital Song Sales chart. The moment was a milestone: a gritty, locally grown sound that had long been dismissed as “too much” for mainstream respectability was now backing a scene in a Disney+ production.

Even TikTok producers and DJs are splicing mahraganat loops into Afrobeat sets and electronic mashups (and foreigners are increasingly drawn to it). Tracks by Hassan Shakosh, Omar Kamal, and Hamo Bika have soundtracked TikTok dance challenges and meme edits far beyond Egypt’s borders, turning what was once local street music into something that now sparks curiosity, Shazam searches, and playlists in places like Brazil, USA, and France. Egyptian music, in all its forms, is living in a constant loop of remix and rediscovery.

It’s this duality that defines the new wave: production that’s almost industrial or techno-adjacent, paired with vocal cadences that still carry the slang, swagger, and social codes of working-class Egypt. It still sounds like home, but now it hits different; not because it’s been diluted, but because it’s being reinterpreted through the aesthetics of chaos Gen Z is increasingly drawn to.

The last few years have collapsed the old borders between genres. What used to be clearly defined lanes (pop here, mahraganat there, rap in its own bubble) have now melted into one giant shared frequency. In the past, we argued about categories. Today, it’s all about energy. Gen Z listeners aren’t asking is this rap or shaabi?, they’re asking does it hit?

In raves from Dubai to Berlin, the genre’s clashing melodies are being reframed as “edgy”, part of a larger post-colonial aesthetic turn that celebrates the raw and unruly. But let’s be clear: the same sounds now hailed as “cool” were once shamed as bee2a.

The term bee2a, a class-coded Egyptian word implying something uncouth or lowbrow, hung over mahraganat like a curse for years. Even those who danced to it behind closed doors would rarely admit to liking it in public. But Gen Z, with their TikTok-driven aesthetic democracy, are changing that.

Today’s audiences don’t flinch at Auto-Tune or chaos. They crave texture, experimentation, weirdness. And mahraganat has always had that in spades. The genre’s DIY ethic, its attitude, and its rawness make it primed for Gen Z’s taste shift toward anti-perfection. If trap, Jersey club, and baile funk got their glow-up, why not mahraganat?

That’s the question at the heart of this moment. Mahraganat didn’t ask to be saved. Its artists didn’t wait for permission to go viral. However, the mainstream love it’s receiving now, repackaged through cleaner aesthetics, listened to by cooler kids, and more palatable collaborations, is being filtered through artists with more privilege, mobility, and digital capital. Are they amplifying its power, or softening its edge?

To be fair, these artists aren’t erasing anything. If anything, they’re translating. But translation comes with choices. What gets lost in the remix? And who decides what version of mahraganat is worthy of wider platforms? Artists like Hamo Bika, Sadat, and Oka & Ortega laid the groundwork without permission or prestige. They blasted speakers from tuk-tuks, dodged bans, and went viral through sheer force of energy. Their grit made the genre. But it’s newer, more globally-aligned figures who are now getting to reframe the story.

Mahraganat’s next chapter might not be about rebellion, but about storytelling. Who gets to tell the story? And will its rawness survive the algorithm? The genre doesn’t need a saviour. It needs a memory. One that remembers who built it, why it mattered, and what it meant before it was ever called “cool.”

For more stories of music, regional and international, visit our dedicated archives.