When Hussain AlMoosawi (Instagram) returned to the UAE in 2013 after years abroad, he didn’t immediately reach for his camera. At the time, he was still mentally immersed in the streets of Melbourne and the typologies of Western cities, spaces he had spent years observing, photographing, and understanding through their overlooked architectural patterns. “It took me a little more than two years to start using my camera methodically,” he reflects. “I was still consumed with the subjects I photographed in Melbourne, and travelling to Europe every now and then gave a little breather, as my brain was still preoccupied with typologies typically found in western cities.”

What eventually brought him back to photography in the UAE wasn’t a grand architectural statement, but something humble—semi permanent objects. “Plenty of observation took place before I was reunited with my camera in 2015, yet to only photograph overlooked and semi permanent subjects such as construction fences,” he says. That re-entry into visual practice would soon lead to a deeper engagement with the UAE’s built environment—particularly the often-ignored structures that quietly define the urban experience.

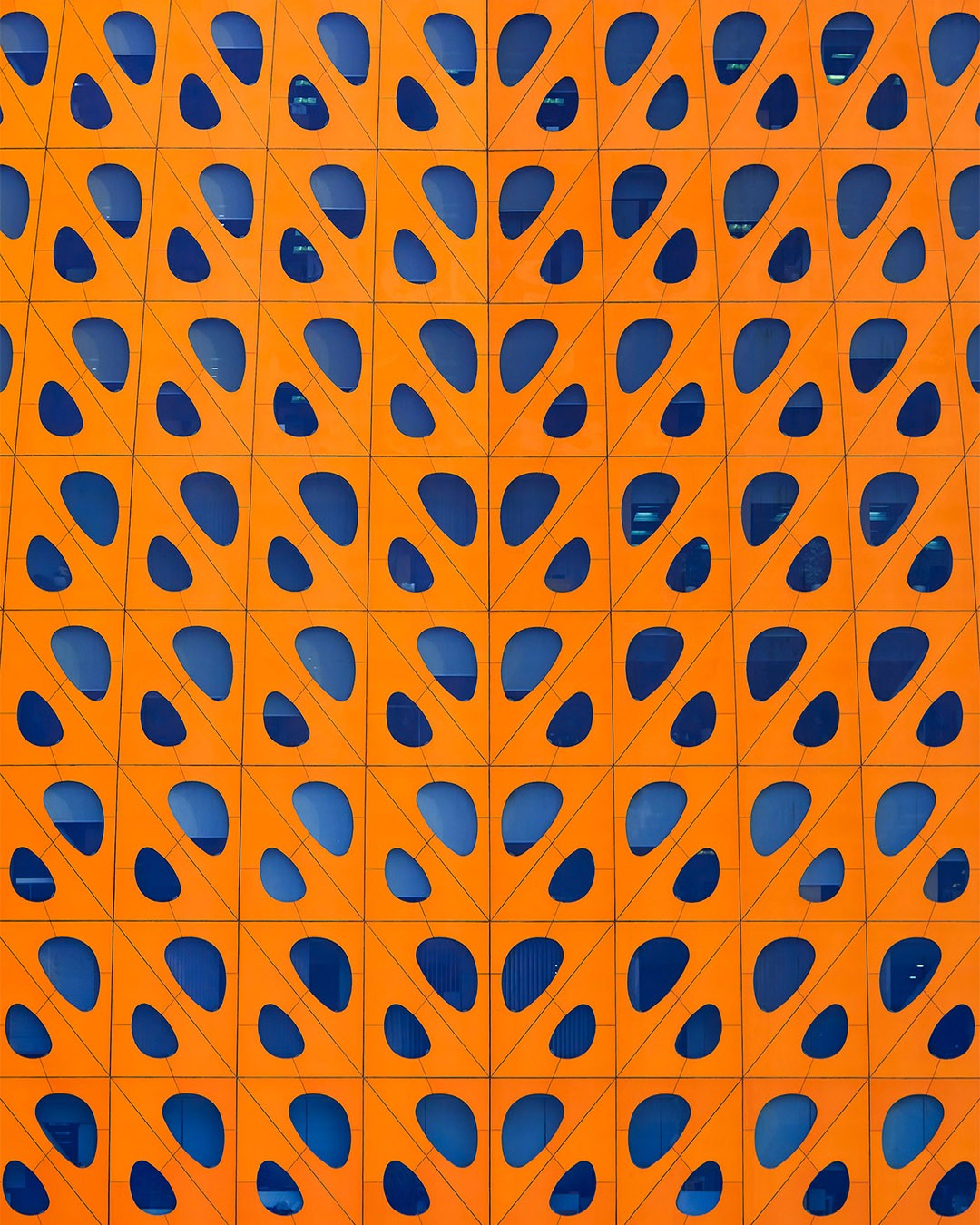

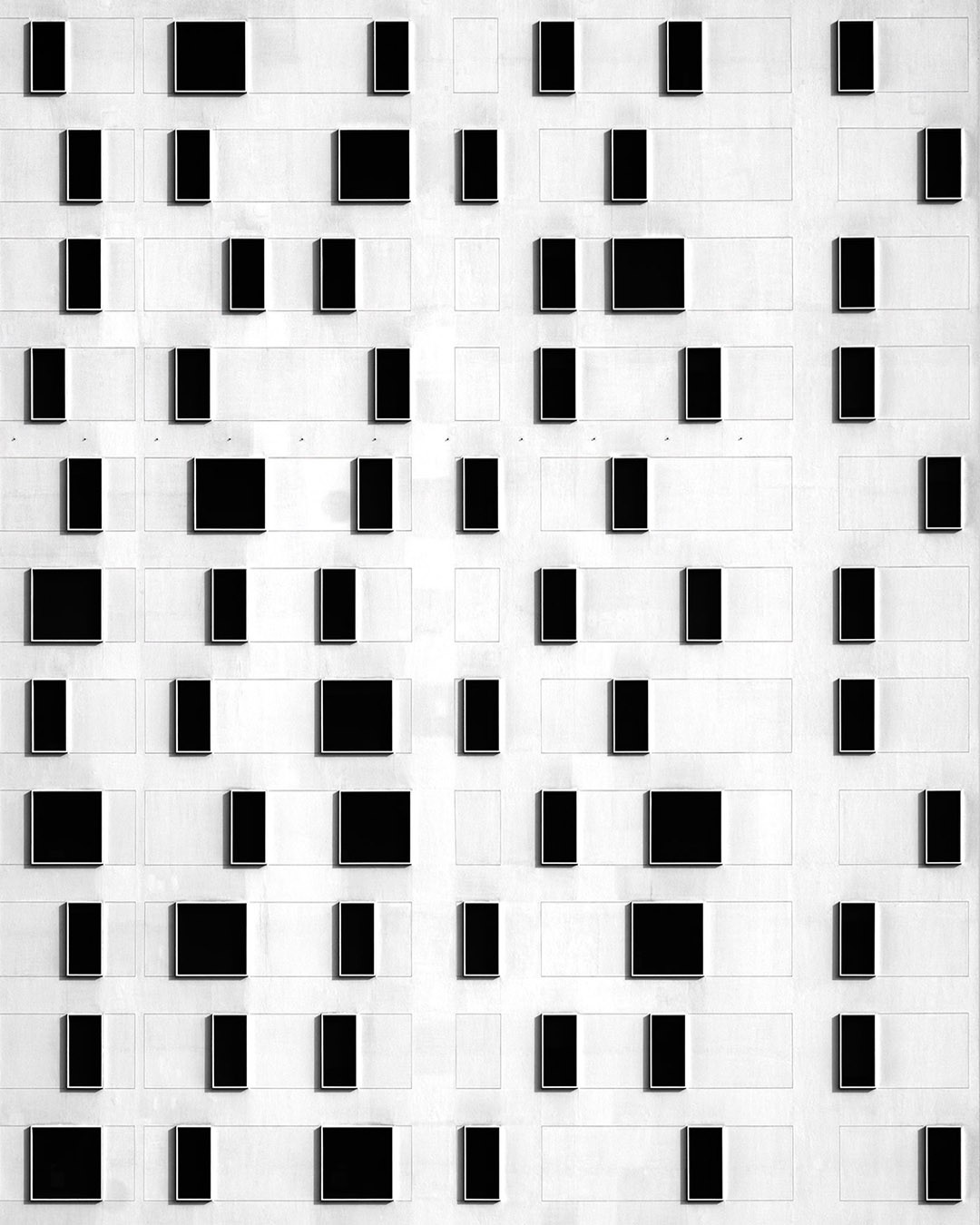

“I wasn’t photographing buildings for their style,” he explains, “only following those that feature split unit AC systems, which spoke to me purely for the aesthetics.” It was this visual instinct—this search for patterns, order, and character—that shaped the foundation for what would become his long-term project, Facade to Facade, which he formally began in 2017.

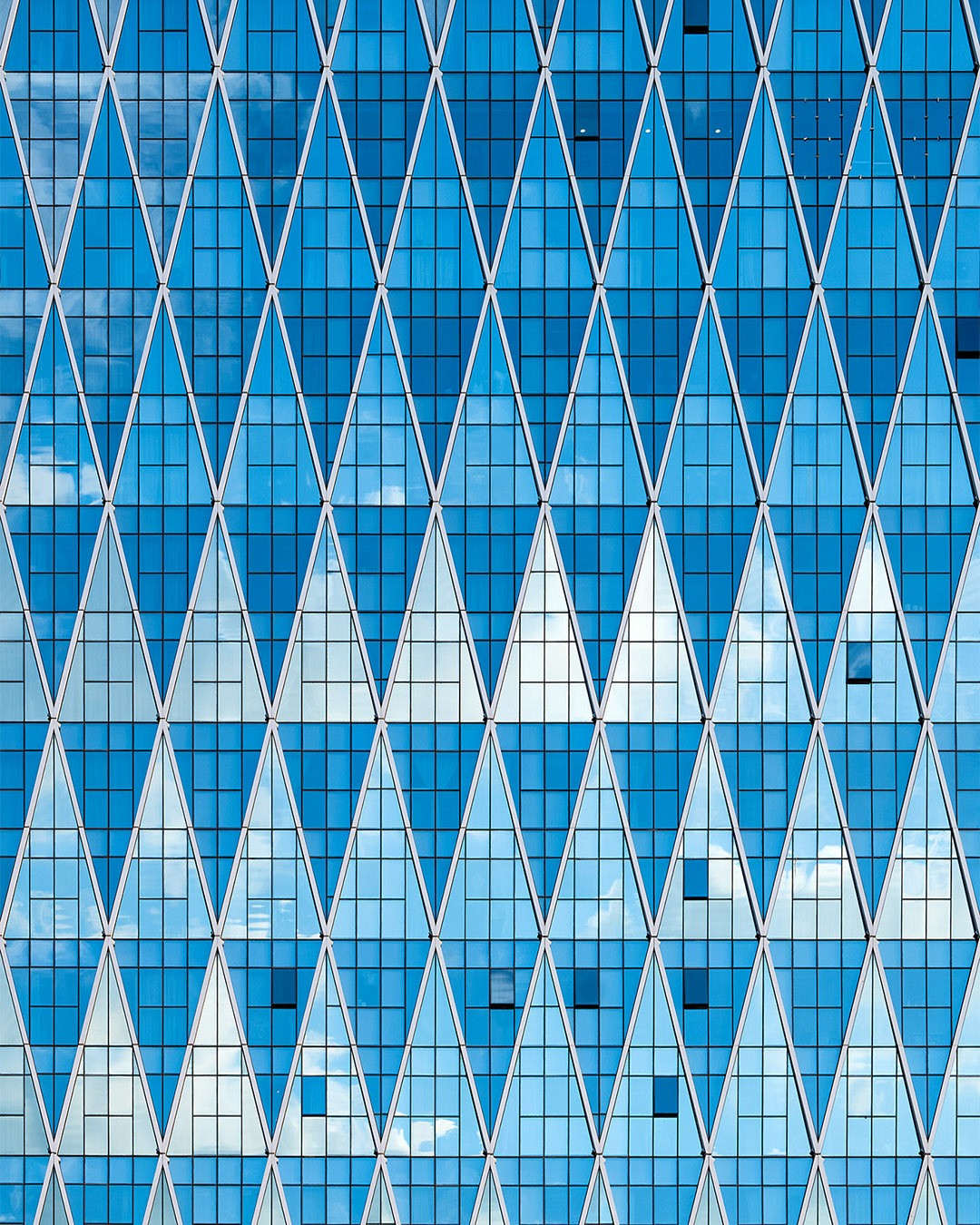

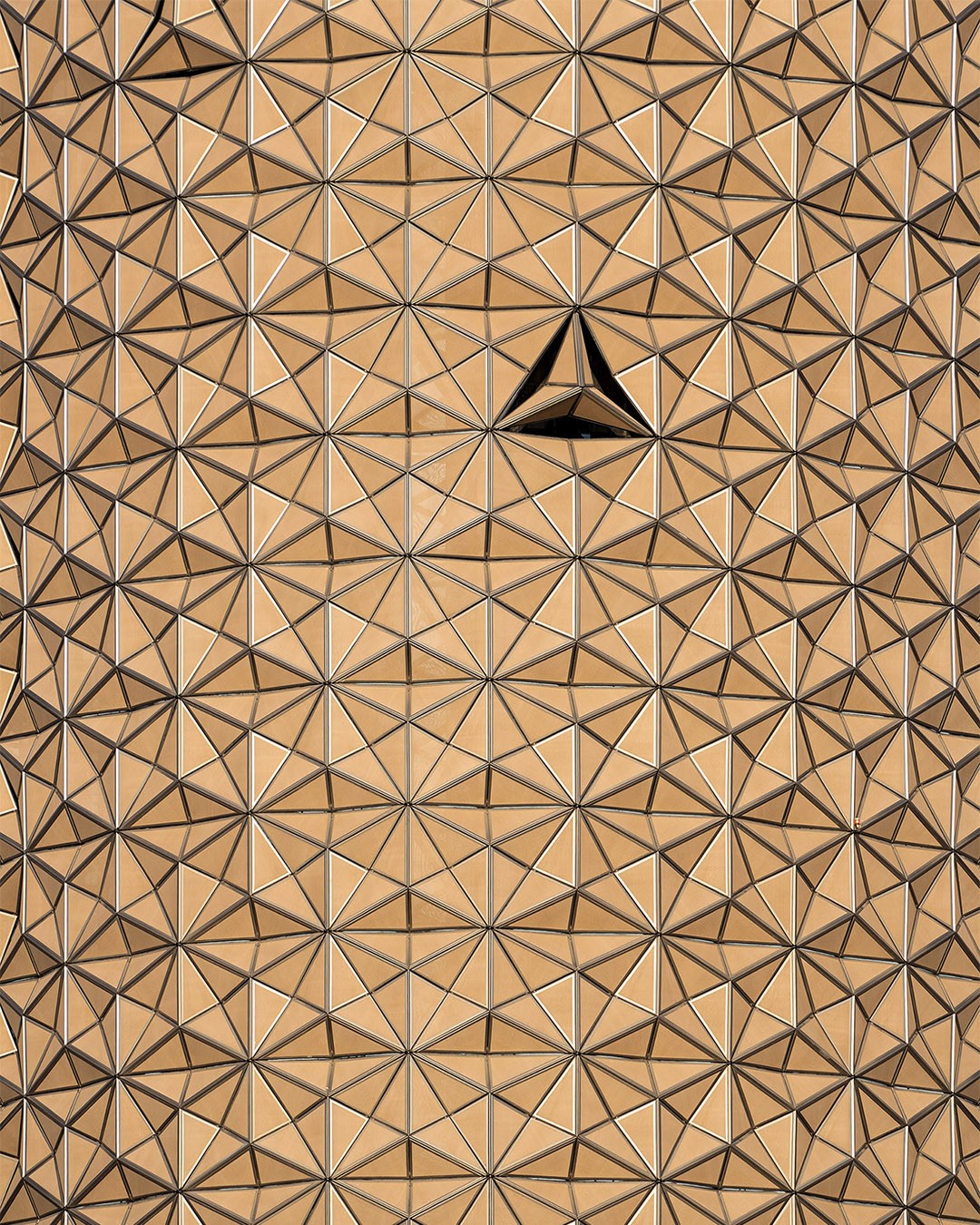

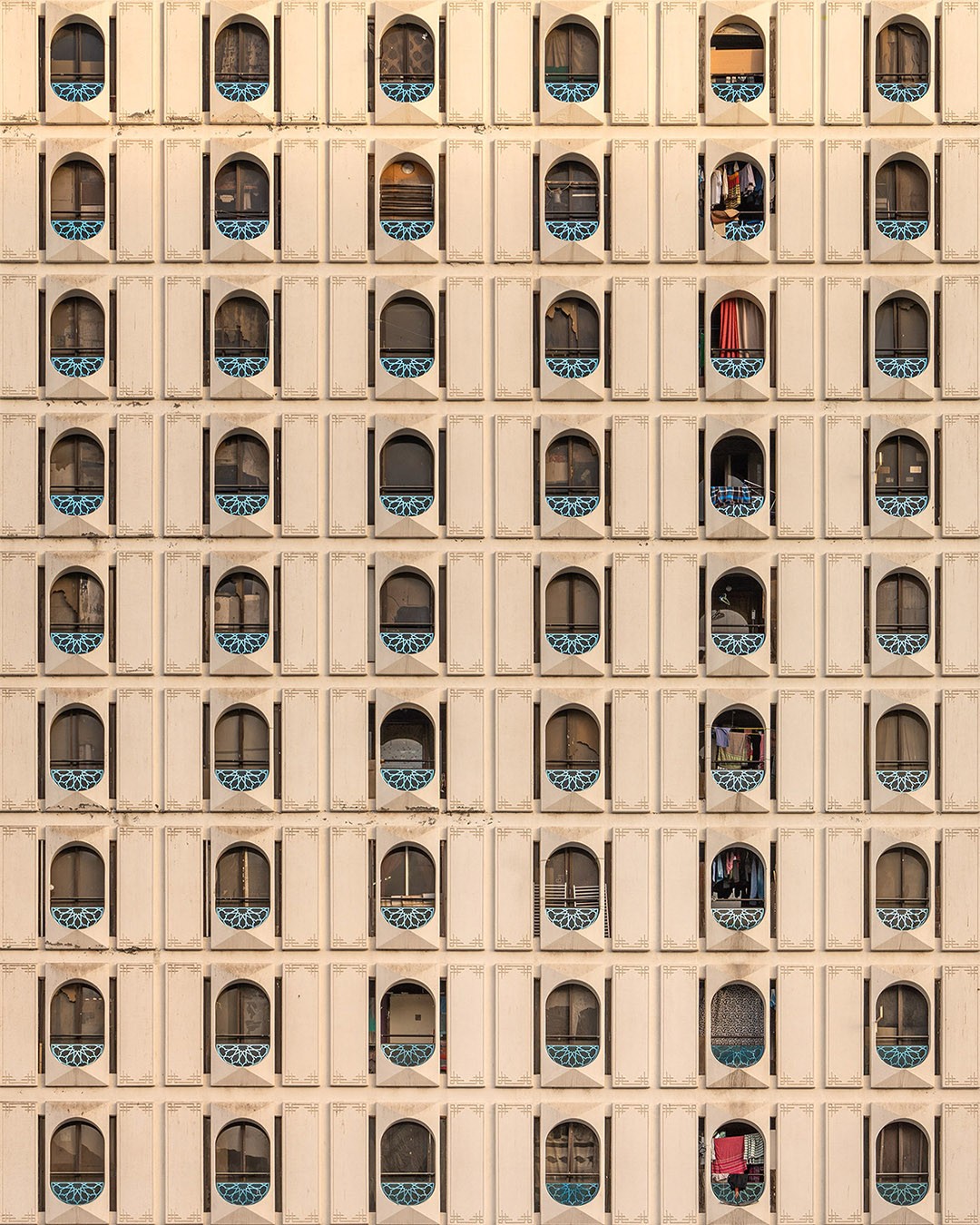

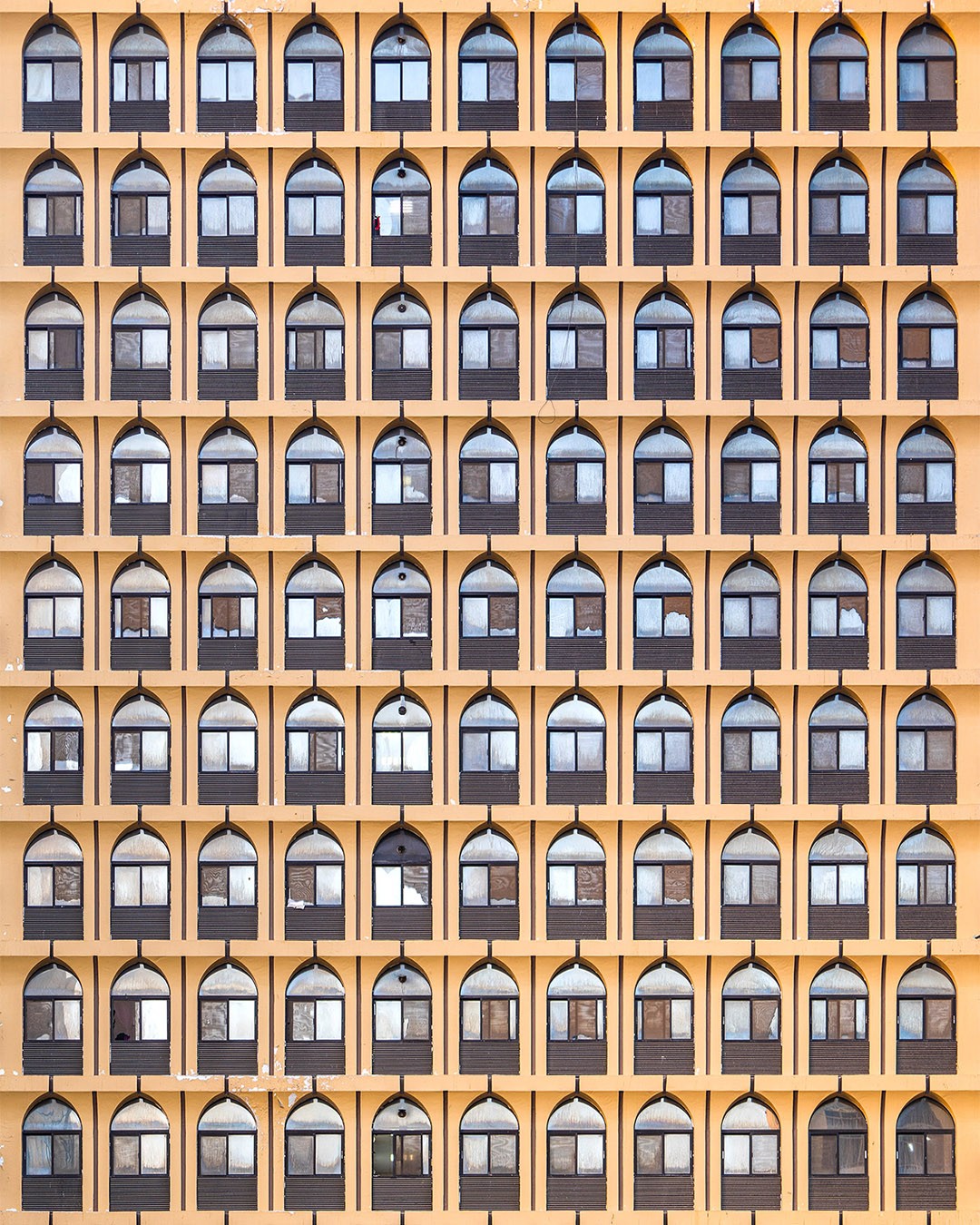

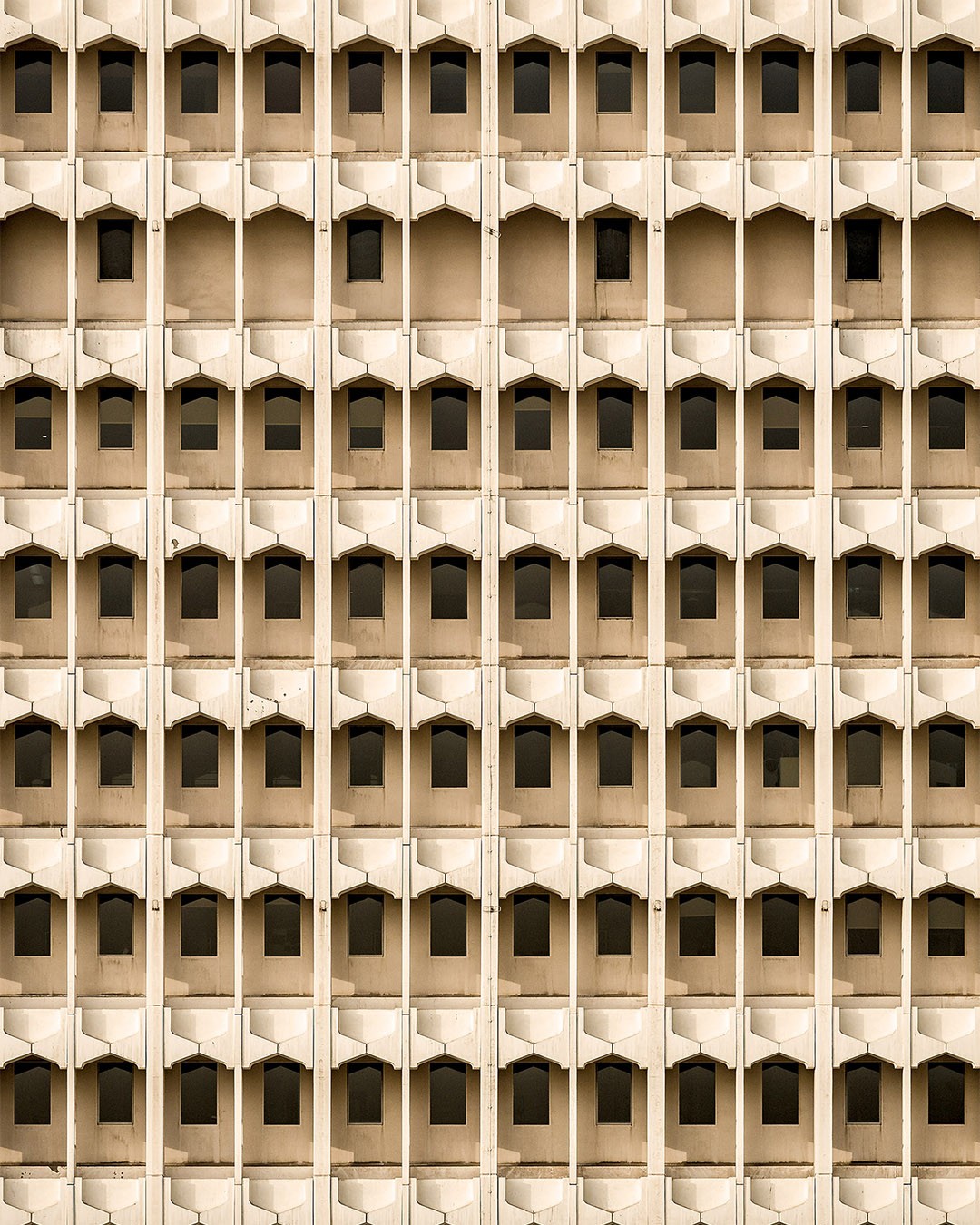

The series was born out of symmetry and memory. “From my recollection, the first building I photographed was DWTC (completed in 1979), commonly known as Burj Rashid. Growing up in Dubai, this building took the centre stage and was highly connected with snippets of childhood memories. Photographing it was a no brainer, and I wanted to acknowledge its importance after it got overshadowed with higher skyscrapers around it,” says AlMoosawi. But a review of his archive reveals that the first photo he took for the project was actually of Liwa Tower in Abu Dhabi—a more contemporary structure. “These two photographs do encapsulate what I was and still trying to do with the project: to evenly document the modernist era (roughly what’s built between the 70s–early 90s) and everything contemporary, and symmetry then was the pattern that helped me navigate through buildings from different eras,” he says.

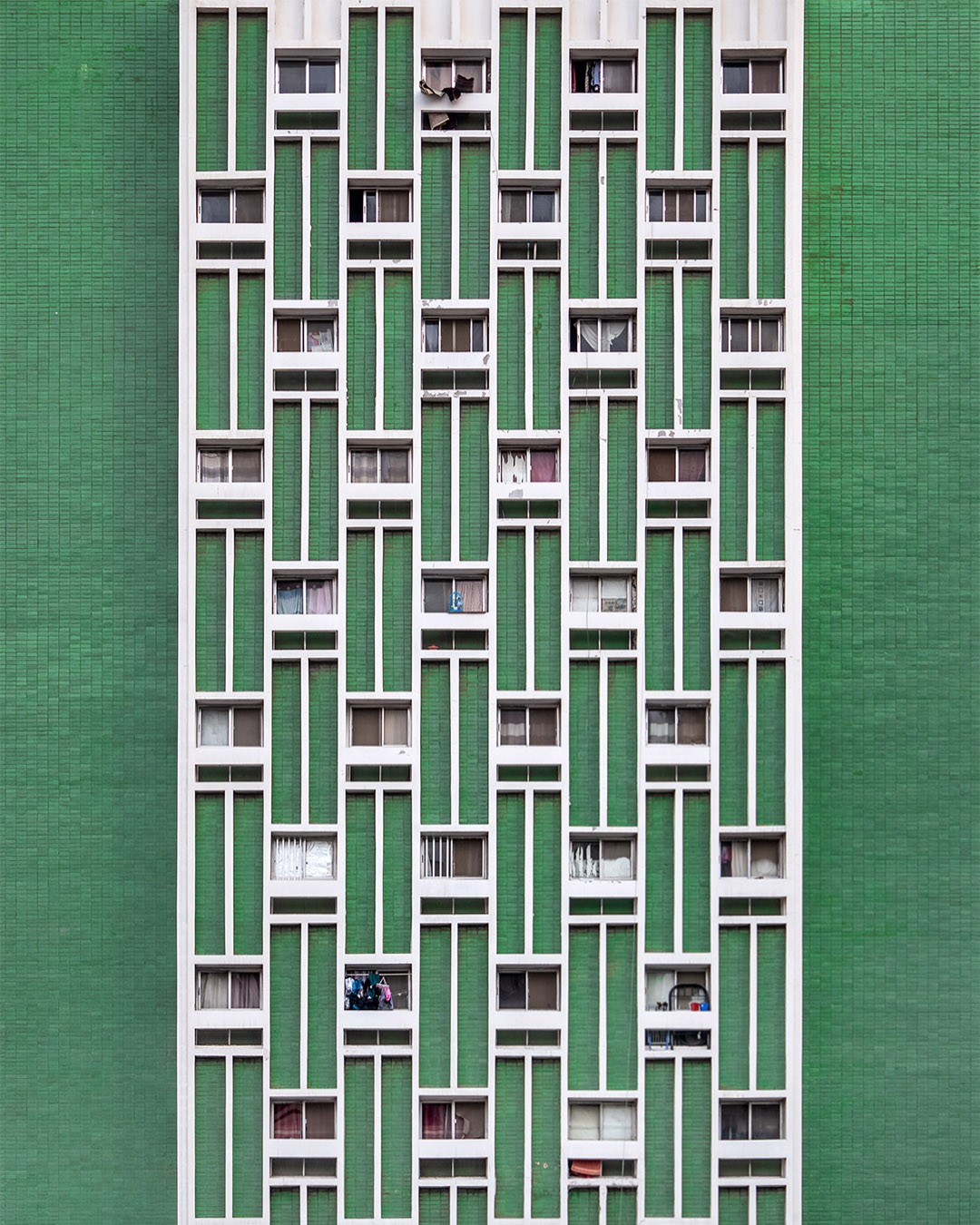

His desire to “re-imagine the city as if it were the ‘80s” is often read as nostalgia, but for AlMoosawi, it’s something more analytical than sentimental. “In few words, that era represents my early childhood, the time when cities in the UAE were developing but haven’t yet experienced the real estate boom, which took place around mid-2000s. When I say re-imagine, I do not mean it in a sense of nostalgia, but to clearly try to experience those modernist elements and how they shaped the city’s identity.” It’s a way of looking at the past not to remember it fondly, but to understand it critically—as an architect or planner might.

His education in visual observation was shaped during his years in Australia. “To begin with, I did not pay much attention to urban development before going abroad. What made me gradually do that in Australia is my interest in documenting the little details of the built environment, which only happened when my understanding of design matured.” That transformation took place in Melbourne, where he developed an artistic, almost intuitive, practice of documenting urban life. “The quest was pretty much artistic and personal. To my awareness, it wasn’t relevant to any type of discourse,” he says. But once back in the UAE, that same method began to resonate more deeply—both with him and with a wider public, “I applied the same approach of looking into details—albeit with facades I broadened my perspective—but happened to discover that what I’m doing is of importance to the general public and experts alike.”

AlMoosawi believes density is a powerful tool in city-making, not just functionally but emotionally, saying, “Photographing mid and high-rise buildings wasn’t only in the name of creating beautiful pictures, but for the fact that I still romanticize density as an ideal medium to organize us in cities—a medium that takes away some personal space, but creates better social connectivity. I live in a suburban townhouse, but deep within I aspire to live in an apartment building from the ‘80s, many which were built with higher standards than the ones built today. I’ll probably never make this move, but photographing those buildings satisfies something within.”

Facade to Facade is filled with subjects that many might overlook: dusty mid-rise buildings, commercial blocks, forgotten urban zones. “Many of these buildings are well and alive, yet some of their localities shifted from being commercial and entertainment hubs,” he says. “If we take Dubai as an example, Bur Dubai and Deira used to be where people would go for shopping and entertainment… my work is about revisiting those areas to stress on their significance in shaping the architectural identities of our cities.” These spaces are not frozen in time—they are still evolving, albeit in the shadows of more glamorous development. Even so, AlMoosawi doesn’t confine his lens to the past. “I still photograph everything contemporary, as these buildings one day might represent a type of heritage.”

Still, the urgency of preservation looms. “Hoarding fences around old buildings frighten me. It happened many times that I rushed (or missed) photographing certain buildings due to demolition.” Even so, not every renovation is cause for despair. “Some became duller, others became colourful. Nevertheless, it’s a great thing to see with old buildings.”

And then there’s the question of beauty. “Primarily I’m not looking for beauty, but for an identity. For something that sticks out. It’s almost like people—you might not fully like someone, but you must admit they acquire a sense of character.” His work is driven by this sense of character, not convention. “Some buildings—facades in specific—are beautiful but aren’t necessarily photogenic, or difficult to photograph. I would still photograph them for the sake of documentation, but I might not publish the photograph as something with a standalone value, rather as something that composes a typology.”

Though his photographs have entered broader conversations around collective memory, AlMoosawi remains more invested in heritage than reminiscence. “I’m not much into ‘memory’. I do not like to look back much. I do understand that my audience sees my work from that point of view, which is beautiful because it makes the project multidimensional in its value.” His focus, rather, is on “modern heritage,” especially architecture from the post-unification era. “When I started Facade to Facade in 2017, I took upon myself the responsibility to carry out this project to the furthest extent. The momentum is even higher now,” he says. The project has expanded beyond photography, gaining traction with policymakers, researchers, and the art world. “The challenge would not only be to bring the project into completion, but to also expand it as academic research to elevate this pictorial study to a level that it brings about more insights,” he says.

What emerges in the end is a kind of belonging. “I warm to everything I photograph,” he says. “When I was in Melbourne, the camera wasn’t only a tool that made me better understand the place, but to also emotionally connect to it, in a feeling that I cannot completely describe.” That feeling persists now as he documents the UAE—building by building, block by block. “Returning home after living abroad for eight years gives you a default baggage of complex emotions seasoned with the need to give back. Photographing around the UAE helped me better understand my own country and equally reconnect with the little things I never knew existed.”

By paying attention to the structures we pass by every day without notice, Hussain AlMoosawi has not only redefined what home means for himself—he’s helped an entire generation see their cities with new eyes.

For more stories of art and culture, like this story of Hussain AlMoosawi, visit our dedicated archives.