From the jinn of childhood stories to the khamsa charms of modern fashion, the Arab world’s relationship with horror runs deeper than ghosts. It’s carved into language, ritual, and everyday acts of protection.

Halloween belongs to the West, or so we’ve been told. A season of pumpkins, slashers, and suburban hauntings. However, in the Arab world, horror never needed a holiday. It has always lived with us, whispered through childhood stories, tucked into religious verses, stitched into our jewellery, and carried in the language of protection.

Long before cinema, oral storytelling was the region’s original horror genre, a way to pass down moral lessons and keep children in check. These tales were about boundaries, the desert, the dark, and disobedience. One of Saudi Arabia’s oldest cautionary tales, Humar Al-Qaylah (The Midday Donkey), tells of a grotesque creature (part human, part donkey), who appears at noon to harm anyone caught outside. Parents told this story to keep children from wandering out during the midday heat, a mix of mythology and maternal logic wrapped in fear. Like many Arab legends, Humar Al-Qaylah blurs safety and superstition. Here, the monster isn’t just a threat; it’s a metaphor for care disguised as terror.

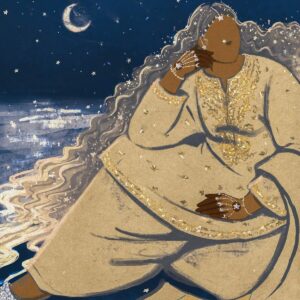

Entirely different in nature are the Jinn, intelligent supernatural beings mentioned in the Quran created from “smokeless fire” who exist in a parallel world. They possess free will and can be good, neutral, or malevolent, acting as agents of extraordinary luck, bad fortune, or possession. Even linguistically, Arab horror begins with what can’t be seen. The Arabic word djinn (جنّ) comes from the root ج ن ن, meaning to conceal, to be hidden, or to lose one’s mind. From the same root comes junoon (جنون) — madness — as if to say, to encounter the unseen is to risk losing reason.

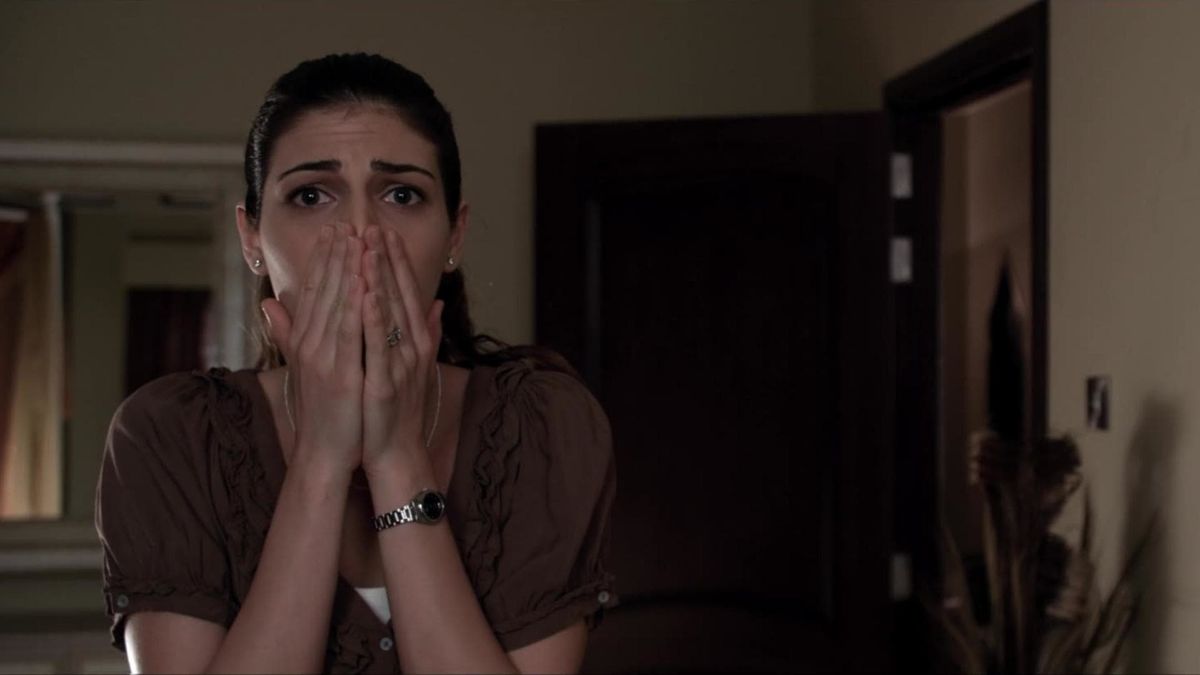

They remain a powerful narrative device today. In modern Arab horror cinema (such as films from the UAE, Jordan, or Egypt), the Jinn are a recurrent, terrifying figure. They are used to explore deep cultural fears, critique societal pressures, or personify emotional and psychological trauma in a way that is distinctly ancestral, providing a powerful alternative to Western tropes like demons, vampires or ghosts.

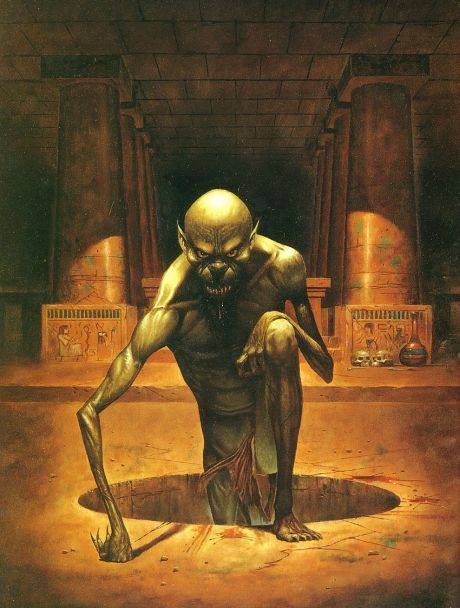

Stories of the Jinn are foundational to Arab folklore, along with figures like the Ghoul and El Nadaha (The Caller). While the Ghoul is a grotesque, corpse-eating demon found throughout Arabic mythology, El Nadaha is a seductive, feminine spirit found in Egyptian folklore, said to call men to the Nile at night, luring them to their doom.

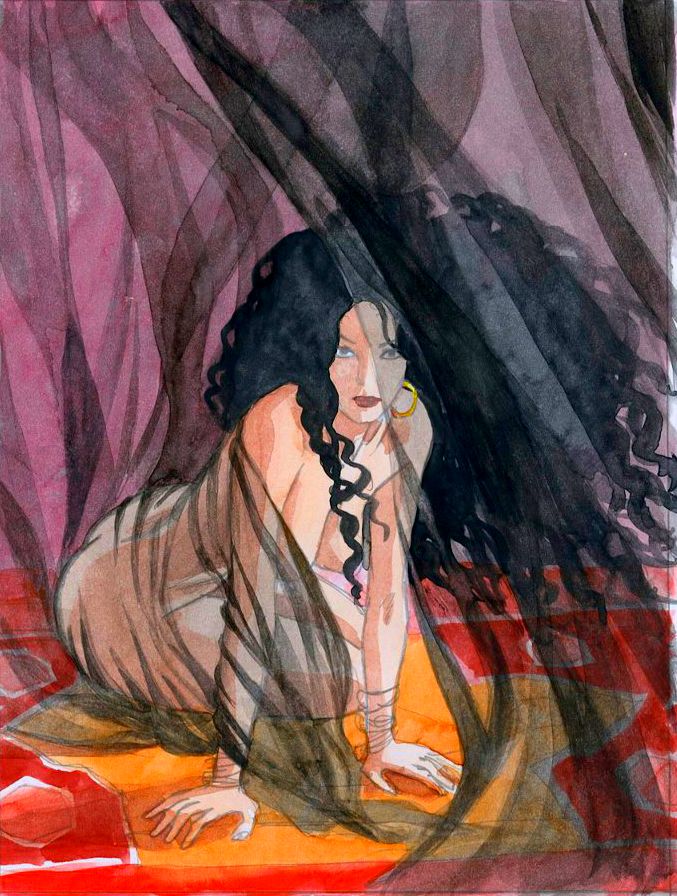

Within that spectrum of the invisible lives an entire bestiary of local legends; some terrifying, some seductive, all uniquely regional. In Morocco, Aisha Kandicha is perhaps the most famous. Said to be a beautiful woman with the legs of a goat or camel, she lures men to rivers and deserts before revealing her monstrous form. Neither demon nor human, Kandicha embodies the ancient fear of desire itself; beauty as danger, the feminine as both sacred and cursed.

In Egypt and Palestine, the haunting takes another shape: Abu Regl Masloukhah, or The Flayed-Leg Man. His story drifts through oral tradition, a figure with one leg skinned to the bone, wandering villages at night. Parents used to whisper his name to scare children indoors before sunset. In both legend and geography, he represents a punishment and a warning, a reminder of the thin membrane between sin and consequence.

Parents used to whisper his name as a warning, a bedtime story edged with moral terror. The tale goes that he was once a disobedient boy who ignored his parents’ advice, venturing out alone after dark despite their pleas. His punishment came swift and cruel: his leg was flayed to the bone by unseen forces, leaving him cursed to wander the earth forever, dragging his wounded limb through village streets at night.

The djinn, Kandicha, Abu Regl Masloukhah, they all dwell in the same cultural psyche that built our cinema, our art, our storytelling. They often share one role, to police behaviour, especially that of the young or the reckless. They embody the collective memory of mothers, turning fear into protection.

On the other side of the spectrum, more so in everyday life, the fear of the Evil Eye (al-ayn) is perhaps the most universal Arab phenomenon, a belief that predates Islam and is found from ancient Mesopotamia to Rome. It is the concept that a person can inflict harm, misfortune, or injury upon another person or their possessions simply by looking at them with intense envy or malice. Crucially, this harm can be unintentional, even a sincere compliment can be loaded with danger.

It demands constant vigilance, to deflect the gaze. This necessity has turned protective rituals into ingrained social choreography: the whispered Masha’Allah (What God has willed), the hidden bead, the piece of salt placed in a new home to ward off envy, the way we still say a’outhu billah when someone mentions the unseen, the khamsa (Hand of Fatima/Mariya). Beyond its religious associations—where the five fingers may represent the Prophet’s family or the Five Pillars of Islam—its function is purely apotropaic, acting as a shield to deflect the envious gaze.

Today, this inherited fear is commercial and highly fashionable. The khamsa, once a humble door knocker and whose name literally means “five”, is now an It-accessory layered into modern jewellery. Regional brands like Okhtein, Azza Fahmy, and Bil Arabi reinterpret these symbols, turning what once guarded the home into wearable protection. Protective talismans are no longer hidden; they are boldly worn, functioning as powerful aesthetic statements that signal cultural belonging and resilience.

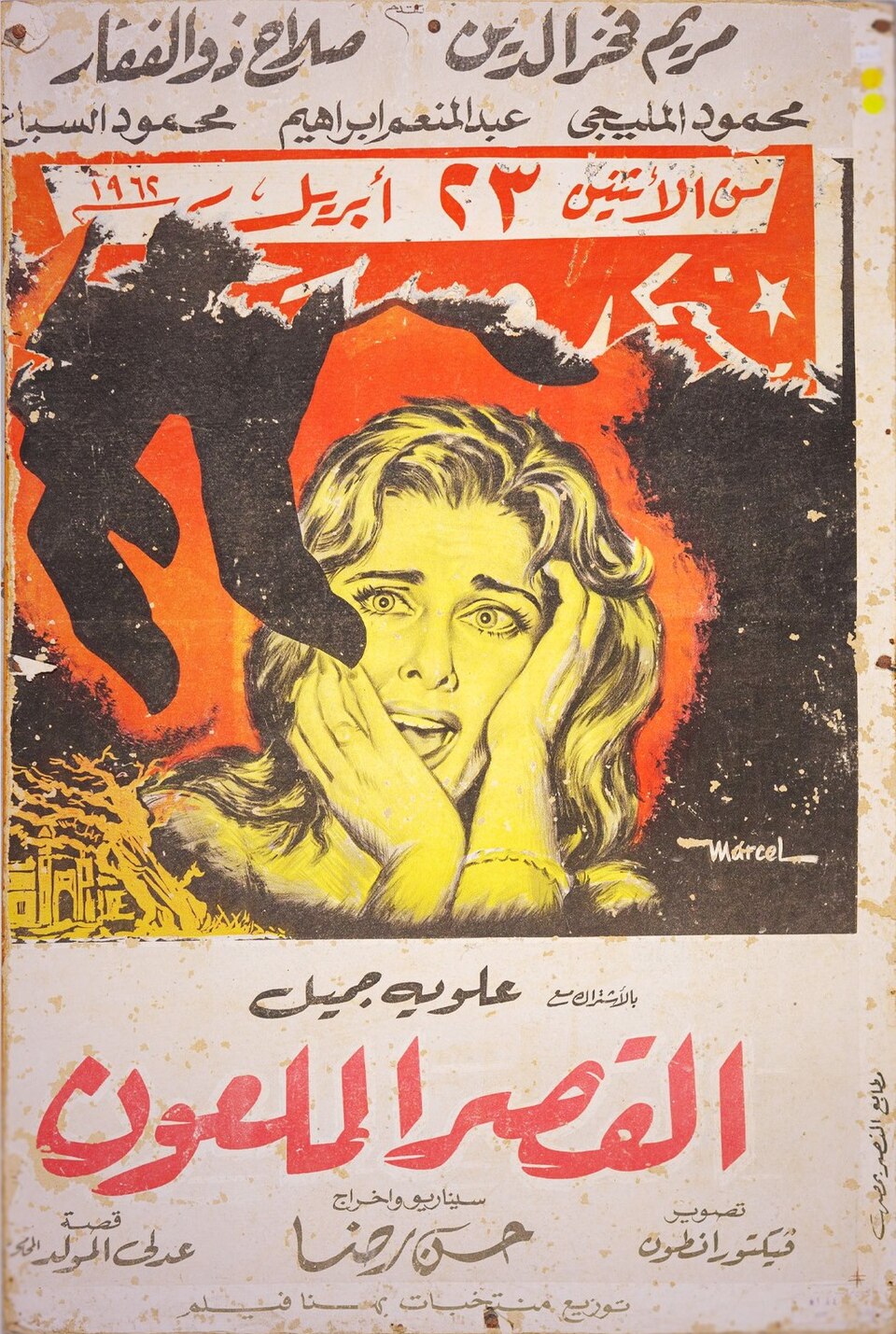

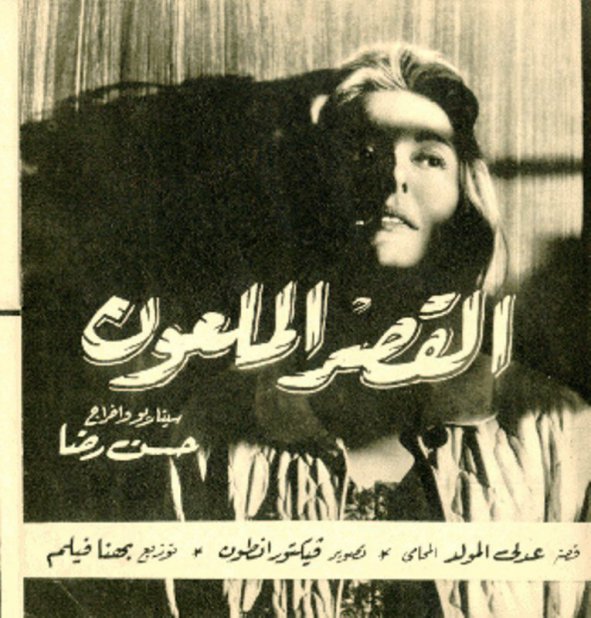

Cinematically, Arab horror has long moved differently from its Western counterparts. While American horror externalizes fear — the masked killer, the haunted house — Arab horror often turns inward, into questions of faith, morality, and the self. Egyptian cinema has long wrestled with the djinn as a metaphor for repression and desire. Early Arab horror found form in The Cursed Palace (1962), one of Egypt’s first gothic films, later evolving through the Emirati supernatural thriller Djinn (2013) and Iran’s cult classic A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014).

In Al Ins wal Jinn (1985), starring Adel Imam and Yousra, the supernatural becomes a vehicle for paranoia about modernity. Three decades later, The Blue Elephant (2014) revived that tradition, marrying psychological unease with mysticism, where tattoos, drugs, and demons blur into one hallucinatory nightmare. Even Warda (2014), Egypt’s first found-footage horror, situates possession as inheritance — the sins and secrets of a family haunting the living.

The Arab world’s horror canon may be small, but its mythology is endless. It sits at the crossroads of the sacred and the profane. When Halloween once again floods global screens with ghosts and gore, Arab horror stands apart: more subtle, older, and closer to home.

For more stories of art and culture from across the region visit our dedicated archives and follow us on Instagram.