He’s got no money, no prospects, no real plan, but he’s got heart. From Titanic’s Jack Dawson sketching in third class to The Notebook’s Noah building a house with his bare hands, the “broke but charming” man has long been the heartthrob of Hollywood’s most iconic romances. These stories suggest that passion, sincerity, and emotional availability outweigh financial stability, even in a world where the cost of love (and living) keeps rising.

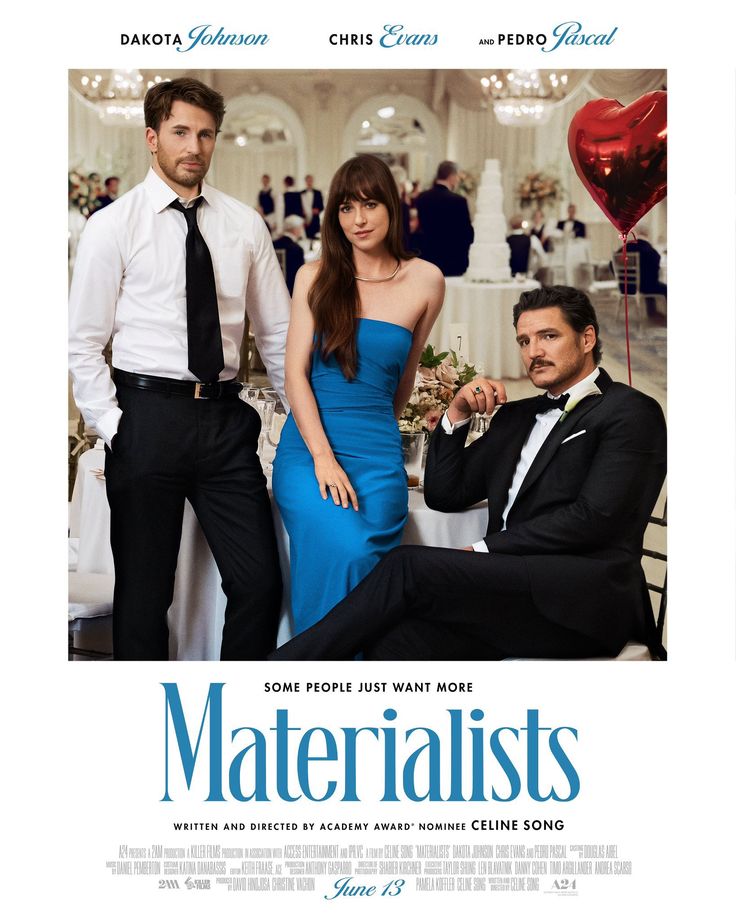

But today’s culture is sending mixed signals. On screen, we still swoon. Off screen? The collective dating mood has shifted. Materialists (2025) revives the classic fantasy: a love triangle where the poor-but-present man competes with the rich-but-ill-fitting one. Online, however, the internet is less forgiving. Songs like TLC’s No Scrubs or Disco Lines and Tinashe’s No Broke Boys double down on a different fantasy, one where love doesn’t come without the lifestyle to match. So what’s really going on here?

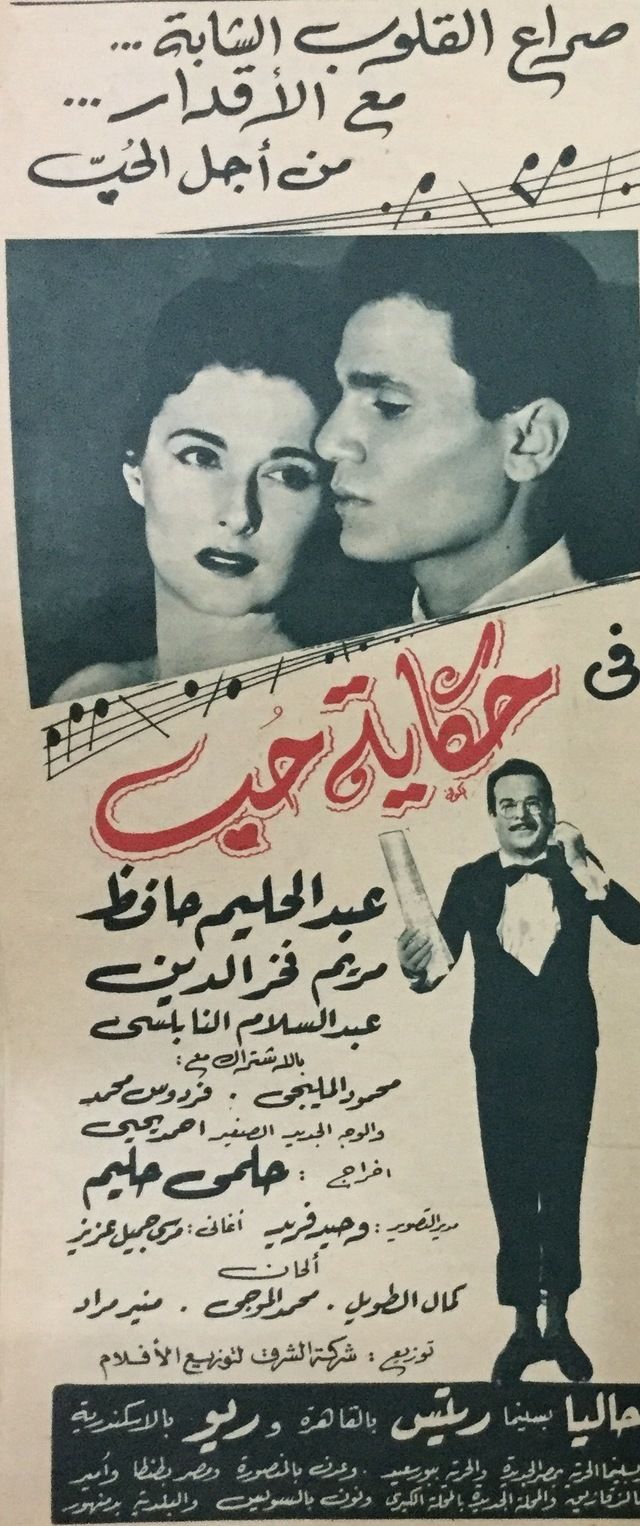

This isn’t just a Western export either. Arab cinema has long played with this exact fantasy. In Egypt’s golden age of cinema, films from the 1950s and 60s gave us romantic leads like Abdel Halim Hafez in Sharea Al Hob, Hekayet Hob, Youm Men Omry, Layaly El Hob, or Maa’boudat Al Gamahir, who, more often than not, fell in love with women above his class. Whether it was Laila Mourad playing the elegant love interest in Laila Bent Al Aghneya’ or Faten Hamama portraying women torn between comfort and connection, the idea of the humble, poetic man fighting for love with nothing but heart and song was a fixture on-screen.

Even in more contemporary Egyptian films and TV series like 2004’s Sana Oula Nasb, 2006’s Gaalatny Mogreman, and 2001’s Rehlet Hob, the trope remains. Romantic comedies and melodramas across the region still cast men who are financially unstable but emotionally available; writers, musicians, waiters, wanderers. Their lack of money isn’t presented as a flaw, but as part of their emotional credibility. In a region where wealth can draw suspicion or cynicism, the broke-but-good-hearted man is still seen as the one with pure intentions. He’s honest because he has nothing to hide. He’s loyal because he has nowhere else to go.

A man who chooses love over lifestyle has its own kind of allure. The “broke but charming” trope offers a fantasy where love isn’t transactional; it’s transcendent. These stories hinge on emotional labour, not luxury. He sees her. He listens. He builds boats and writes letters and cries in the rain.

However, that type of thinking in itself is flawed and gendered. These characters are rarely working-class women falling for rich men. And when they are, they’re framed differently, as gold diggers or social climbers. The broke man, however, is romanticized for not being interested in money. For being pure. Passionate. Real.

But the gender roles flip in a lot of Turkish series. Instead of the broke man with a good heart, it’s often the poor, naïve, but beautiful woman who captures the attention of a powerful, emotionally guarded, and usually obscenely rich man. She’s from the hara, a lower-income neighbourhood, maybe raised by a single parent or working long hours, and he’s the brooding heir, the CEO, or the cold investor with a tragic past. From Love for Rent, and Love, Logic, Revenge, to Love is in the Air and Becoming a Lady, the setup stays consistent: love becomes a ladder, but only for her.

It’s a fantasy rooted in class mobility, but also one that reinforces certain power dynamics. The woman is desired not for her agency, but for her innocence, her “purity,” her endurance. Her social position is often what allows the love story to unfold, because it gives him something to save. And while these stories centre on love, they also embed the idea that the man controls the conditions of that love: the pace, the risk, the future. Her access to safety and status is tethered to his ability to choose her.

The modern dating economy runs on aesthetics and income brackets. The very apps we date on allow us to filter by salary. Social media culture has collapsed ambition into aspiration, and that aspiration into luxury. What does “romantic” look like when a dinner date costs more than rent? When your For You Page is full of #SoftLife content, yacht vacations, and curated boyfriend aesthetics?

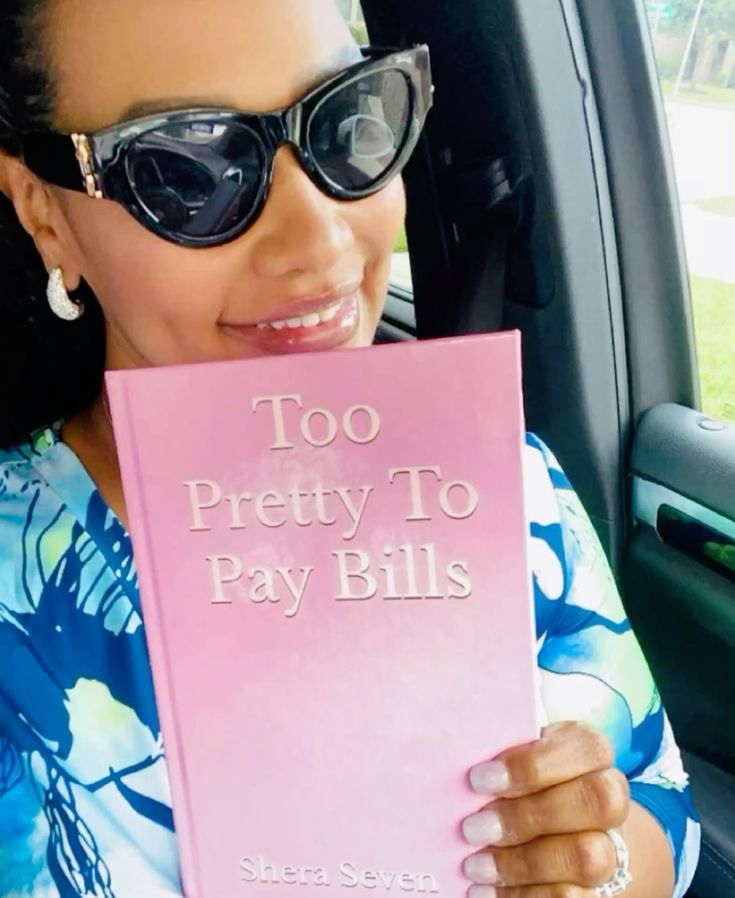

The songs we sing and the tweets we repost suggest a cultural fatigue: I can’t pay my bills, and I won’t pay yours. Today, the loudest voices online aren’t telling you to wait for love, they’re telling you to monetize your femininity. On YouTube, TikTok, and even Instagram Reels, content creators like The Wizard Liz preach self-worth and luxury, while SheraSeven, a self-proclaimed “hypergamy coach”, teaches women how to secure financial commitment from men with catchphrases like “Sprinkle sprinkle”.

In these digital spaces, “broke men” aren’t just undesirable; they’re dangerous. They’re framed as liabilities, emotional projects, or distractions from personal growth. Dating becomes a financial strategy, and romantic labour becomes something to be compensated. It’s a form of empowerment, and when rent is high, salaries are stagnant, and gender roles still ask women to be everything at once, the rejection of broke men starts to sound less shallow and more structural.

Online, the stakes are clear: “If he wanted to, he would — and he’d pay for it.” There’s an empowerment in rejecting the broke man, a reclaiming of power in a world where women are still expected to settle. And yet… we still fall for him on screen.

This is the grey area where film still functions as escapism. The movies let us imagine a world where love doesn’t need logistics. Where a man with nothing can still be everything. Where capitalism doesn’t crush connection. These stories aren’t just about love, they’re about class mobility. Jack Dawson doesn’t just win Rose; he accesses a world he’s been locked out of. And she, in turn, escapes the cold tyranny of her wealth. The trope works because it offers both freedom and fantasy: the emotional man, the subverted class dynamic, the idea that love could be enough.

For more stories of culture visit our dedicated archives and stay across our Instagram.