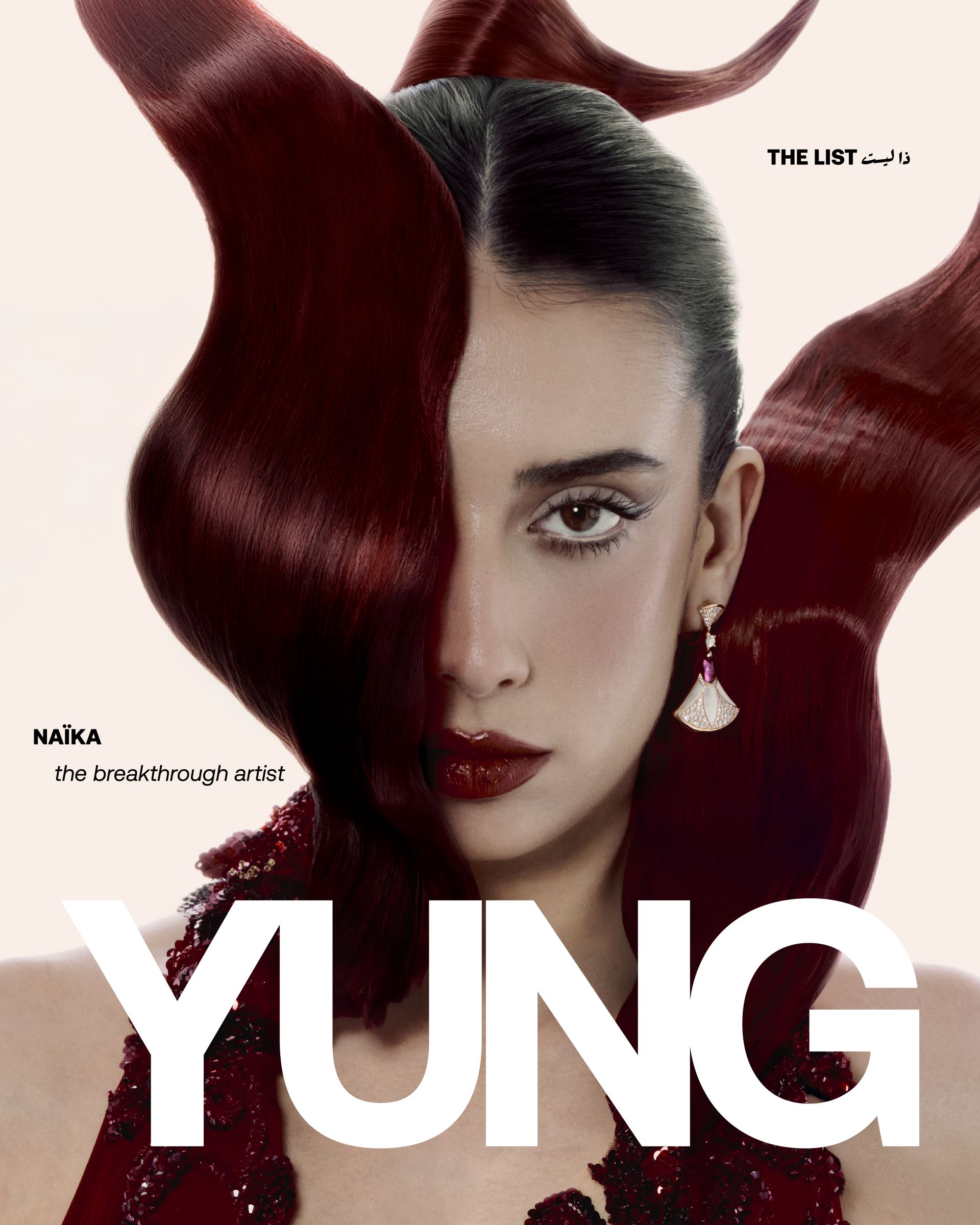

Naïka, YUNG’s “Breakthrough Artist of the Year” in THE LIST 2025, has spent most of her life moving, across countries, languages, rhythms, and expectations. Born in Miami, of Haitian-French heritage and raised between continents, she learned early that belonging wouldn’t come from one place, but from many. For years, that multiplicity felt like a source of confusion. Now, it feels like freedom. “I’ve always had a bit of a dilemma trying to find my place in the world,” she says. “There was confusion, but also so much privilege and expansion. Over time, I’ve come to peace with the fact that I belong to many different places.”

That acceptance didn’t come easily. Growing up across cultures meant constantly adapting — learning how to read rooms, accents, rhythms, and emotional registers. It meant belonging everywhere and nowhere at once. It meant being split across places for so long that dislocation felt like a native tongue — until it didn’t. “It’s a huge blessing,” Naïka reflects. “I can go anywhere and connect. I can adapt.”

In recent years, that sense of belonging has taken on new dimensions. Naïka has been reconnecting with parts of her ancestry she didn’t fully understand growing up, particularly her family’s Middle Eastern roots. “My mother’s ancestors were refugees from the Middle East in the 1800s,” she explains. “It feels like peeling back another layer of myself.” It wasn’t planned or pursued; it simply showed up, the way things that feel familiar often do. “It’s like the Middle East found me before I ever went looking for it,” she says, smiling.

It wasn’t until Naïka encountered the term “third-culture kid” that her lived experience finally had a name. She was part of a community of people shaped by cultural ambiguity, layered identities, and a lifelong search for belonging. “When I found that term, it brought me so much peace,” she says. “It was really comforting to finally have language for who I am.”

This multiplicity surfaces everywhere in her work: in the languages she weaves into her lyrics, the rhythms she gravitates toward, the visual worlds she builds. “It’s part of the fabric of who I am,” she explains. “Creatively, artistically — it’s inseparable.”

Early on, she worried that complexity might be a barrier. “I used to think I was too complicated,” she admits. “Like, how do I present myself in a linear way? Sometimes I wished I was just from one place.” Instead, she did the opposite. She leaned in. “The more authentic I became, the more people actually related,” she says. For her, cultural ambiguity lent direction and purpose.

Still, the question of belonging never really leaves her. “Humans are tribal by nature,” she reflects. “We need belonging. When we don’t feel it, it’s alienating.” Music, for Naïka, became a way to bridge that gap — not just for herself, but for others who live between definitions. “Being able to connect with people who feel the same way,” she says, “that’s really special. That’s community.”

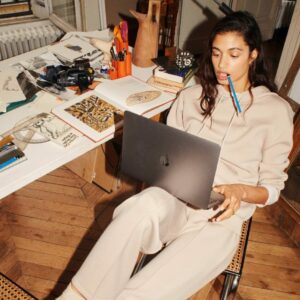

For her, melodies arrive first — loose, unfiltered, emotional — setting the tone before lyrics ever take shape. From there, she listens inward. What’s been sitting with her? What feeling needs space? What truth is asking to be said? “I’m a melody person,” she shares, laughing. “If you don’t tell me to shut up, I’ll just keep going.”

Her phone is constantly filling up with fragments: unfinished lines, song titles, stray ideas caught mid-thought. There’s no fixed formula. “You can’t really predict the process,” she explains. “I usually start with melodies to see the vibe, the essence. How it’s making me feel — story-wise, lyrically. What’s been on my mind.”

Rather than guarding her ideas, Naïka treats songwriting as a shared terrain of openness and collaboration. Working closely with producers and writers she trusts, she builds songs layer by layer, allowing them to evolve beyond what she could imagine alone. “It’s a blank canvas,” she says. “We co-create. They bring things I wouldn’t have thought of by myself.”

Her sound, a melting pot of pop, R&B, and global influences, reflects that emotional openness. Pop forms the foundation, she explains, but it’s shaped by the rhythms and textures she grew up with. “World music is quite a broad term,” she notes, “it’s the category my sound often falls into, even though what I’m actually doing is pulling from the cultures that shaped me.”

She keeps playlists not just of songs, but of sounds; percussions, synths, textures that spark something visceral. “Sometimes it’s like, why don’t we try this element? Or that rhythm?” she says. The process is experimental, intuitive, moving by feeling rather than the rigid grammar of genre. Trial and error is the point.

There are a few references she keeps close, not as influences in the traditional sense, but as markers she checks in with. Bob Marley, for the way his music could hold joy and grief at the same time without ever forcing either. Cesária Évora, for the softness, for how longing could exist inside something almost bare. Somewhere between them sits the Haitian saying “konpa synth”, it surfaces instinctively. Together, they don’t point her in one direction so much as keep her oriented.

And what anchors it all is trust. Trust in her instincts, in her collaborators, and in the idea that emotion, when followed honestly, will always find its form. However, that wasn’t always the case for the singer. When she first moved to Los Angeles in 2018, she entered an industry that spoke in numbers, formulas, and expectations. It was a world where success came pre-packaged, melodies engineered for virality, songs built to fit radio logic, creativity measured by outcome.

“At the time, it felt very mathematical,” she recalls. “Everything was geared toward making hits, toward cookie-cutter success.” For someone whose process was rooted in instinct and emotion, the environment felt constricting. “I felt really caged,” she says. “What felt authentic to me didn’t feel like what was going to make money.”

She tried to adapt. Like many young artists finding their footing, she questioned her instincts, wondering whether they were too personal, too risky, too untranslatable. “Back then, I didn’t trust myself,” she admits. “I didn’t know what I was doing on my own.” The doubt lingered; not because her vision lacked clarity, but because it hadn’t yet found support. “I also didn’t grow up in an environment that celebrated this kind of career.”

What changed wasn’t a single breakthrough, but a slow recalibration. Naïka began paying closer attention to what felt real rather than what felt acceptable. She stopped chasing validation and started listening inward. “Over time, I learned to really rely on my authenticity,” she says. “To trust what feels honest and true to me.”

Risk stopped feeling like a gamble and started feeling like honesty. The music she wanted to make was always capable of reaching people — it just didn’t arrive neatly pre-approved, wearing the right instructions. The EPs she released during that period became acts of exploration rather than destination points. They were spaces in which to experiment, to fail safely, to discover her sound in public. “That’s why I made EPs,” she explains. “I was figuring myself out — discovering who I was and how I wanted to present myself to the world.”

When Naïka speaks about Eclesia, her debut album, she’s quick to correct one assumption. This isn’t a pivot. It isn’t a new era manufactured for momentum. “It’s funny you mention that,” she tells YUNG, when the idea of reinvention comes up. “It’s not a different era. It’s me finally being able to show people that I’m here.”

The album’s foundation arrived early, long before the final tracklist took shape. It began with a single word. “The title came first,” she reveals. Eclesia. From the outset, she knew what the project needed to be: an introduction. Not just to her sound, but to her interior world. “I knew it was going to encapsulate all the different elements that make up who I am.”

Releasing in February of 2026, the album unfolds like a journey, moving through textures, moods, and emotional registers without asking for cohesion in the traditional sense. “It feels like travelling,” she says. “Different places, different topics, different sounds.”

For Naïka, Eclesia marks the moment where the pieces finally had room to coexist. After years of building without consistent infrastructure, the conditions shifted. “I didn’t start with support or resources,” she says. By 2023, she was starting again from zero. This time, intentionally. “It took time to build my foundation, and my team.”

Among Eclesia’s most affecting moments is “What a Day,” a track that carries weight. It’s not the difficulty of writing it that lingers; it’s the reality of what it holds. “It wasn’t hard to write in terms of process,” Naïka says. “It was hard because it’s very real.” The song expands gradually, moving from the internal to the collective, from mental states to material consequences. “It starts in your head,” she explains. “Then it grows — immigration, illness, social injustice, political corruption. And it ends with the planet, and how we’re affecting it.”

The challenge wasn’t expression, but restraint. “There’s so much injustice in the world,” she says. “So much to talk about. We had to choose what to include, and what to leave out.” That limitation frustrated her, even as it clarified the song’s purpose. The track doesn’t attempt to solve anything. It bears witness.

The emotional weight of living — exhaustion, empathy, overwhelm — becomes inseparable from global realities. The song unfolds like a widening lens, proving that intimacy can be a political act in itself.

“The album feels like coming home,” she says simply. “It’s my arrival.” That sense of arrival is less about arrival to an industry than arrival to herself. It holds complexity without apology, allows contrast without explanation, and trusts the listener to follow. In doing so, Eclesia becomes what its name suggests: a gathering.

It’s not just Eclesia. Across everything she makes, Naïka’s visual world feels intimate before it feels styled. Flowers recur. Skin glows. Bodies soften into surreal forms. This sensuality is actually inherited. “My visual world comes directly from how I grew up,” she unveils. “I’m very much an island girl.”

Much of that sensibility traces back to her mother, who shaped her understanding of beauty long before fashion entered the picture. “She’s incredibly original, very creative,” Naïka explains. “Wherever we lived, there were always flowers — on the table, around the house, everywhere.”

In places like Vanuatu, flower crowns and necklaces were part of daily life. These memories still guide her visuals today — the warmth, the softness, the way nature and body intertwine. “That’s my main inspiration,” she puts it simply.

Her relationship with fashion followed a similar path. Growing up, her mother sold clothes and ran stores across the countries they lived in, yet she remained uninterested in brands or labels. “She never cared about designers,” Naïka says. “She didn’t let me care about brands either.” High fashion came later, discovered on her own terms, approached with a sense of childlike curiosity.

If there’s a throughline that carries Naïka across cultures, genres, and phases, it’s that very same curiosity. Not ambition. Not certainty. Curiosity. “I’m a big observer,” she says. Having lived across drastically different environments, she learned early that no place — and no person — can be reduced to a single story. “Everywhere has layers, duality, contrast,” she explains. “There’s always a spectrum.”

That belief extends to faith. Naïka doesn’t follow a specific religion, but she maintains a strong spiritual grounding. “My biggest connection is with the universe, and with God,” she says. “I respect all religions, but I trust in energy, in a higher power. I can’t pretend to understand it — and that’s what grounds me.”

It’s a way of seeing that leaves room for openness. She speaks often of pure wonder, an innocence shaped by exploration rather than naivety. As a child in Kenya, she spent hours learning about insects from a teacher obsessed with bugs and music. “I don’t remember my times tables,” she laughs, “but I know everything about praying mantises.”

Today, this shapes how she navigates success, doubt, and visibility. “It comes in waves,” she says of confidence and imposter syndrome. “Some days you feel on top of the world. Other days you wonder what you’re doing.” She doesn’t cling to either. “I don’t take any of it at face value.”

So she returns to the present. “All we really have is today,” she says. “Not yesterday. Not tomorrow.” It’s a way of thinking that filters through her music, her visuals, and how she moves through the world. Curious, open, unafraid of contradiction.

In living comfortably within the grey, Naïka doesn’t seek to define herself once and for all. She allows herself to keep becoming.

For more stories of music from across the region, visit our dedicated archives and follow us on Instagram.