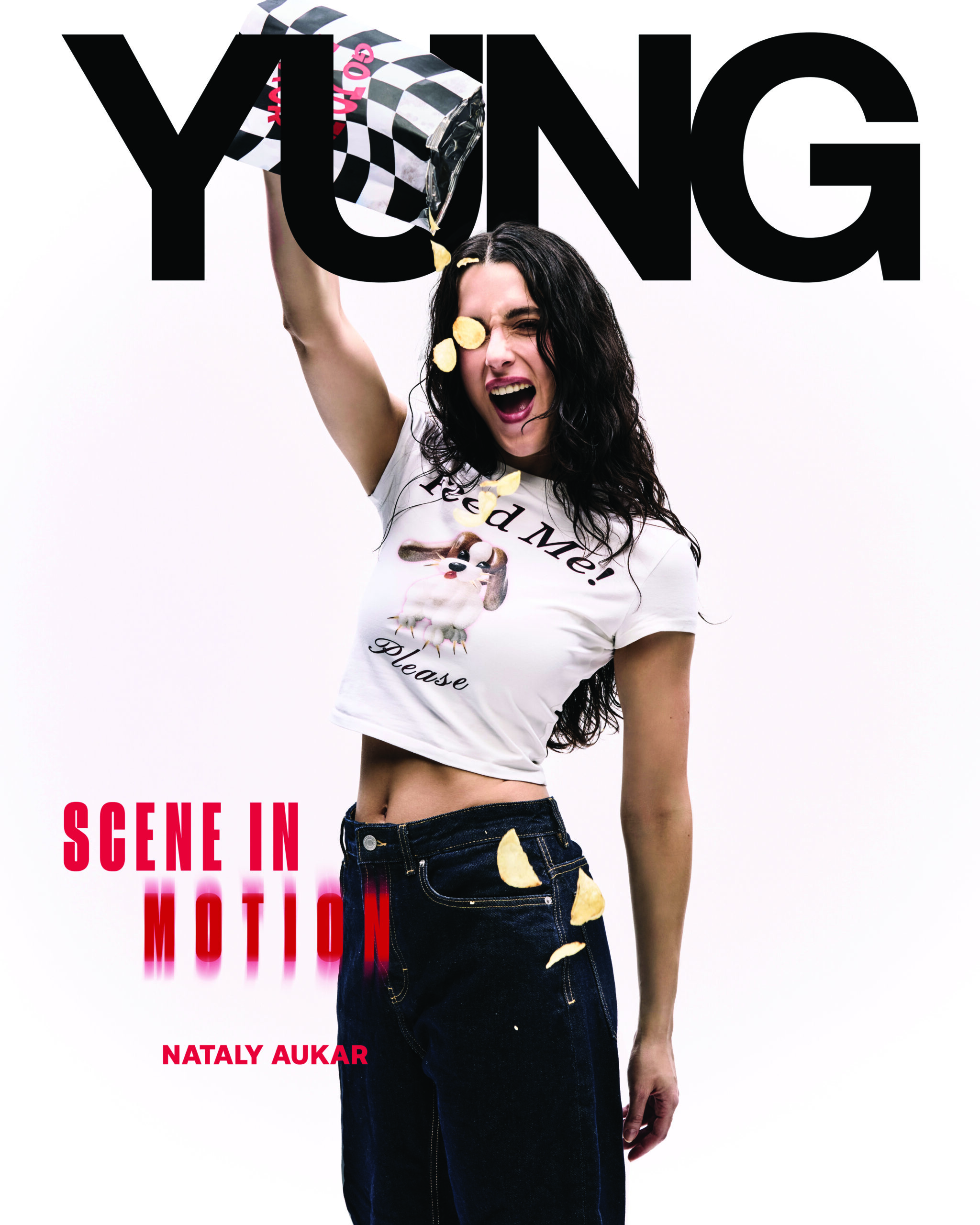

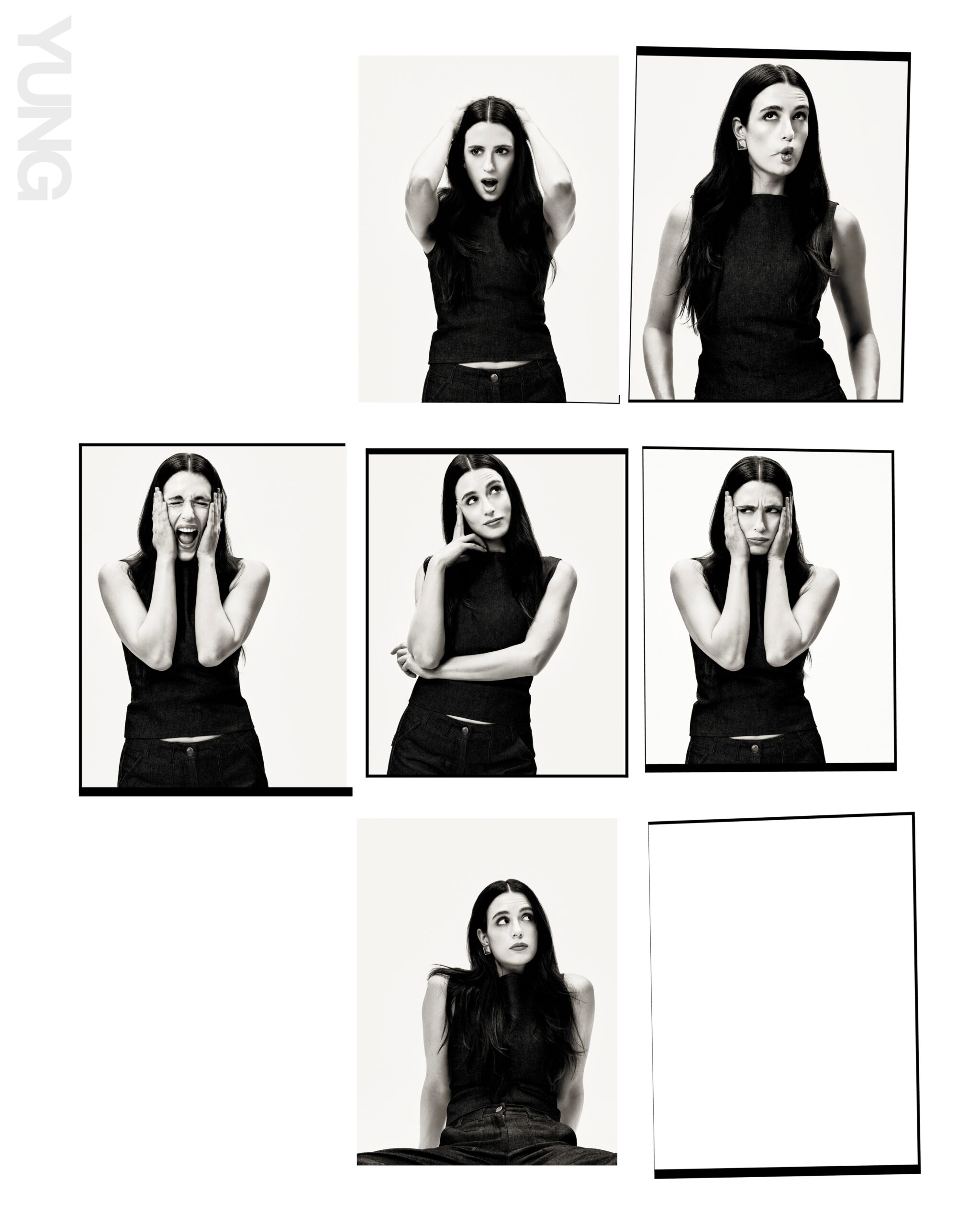

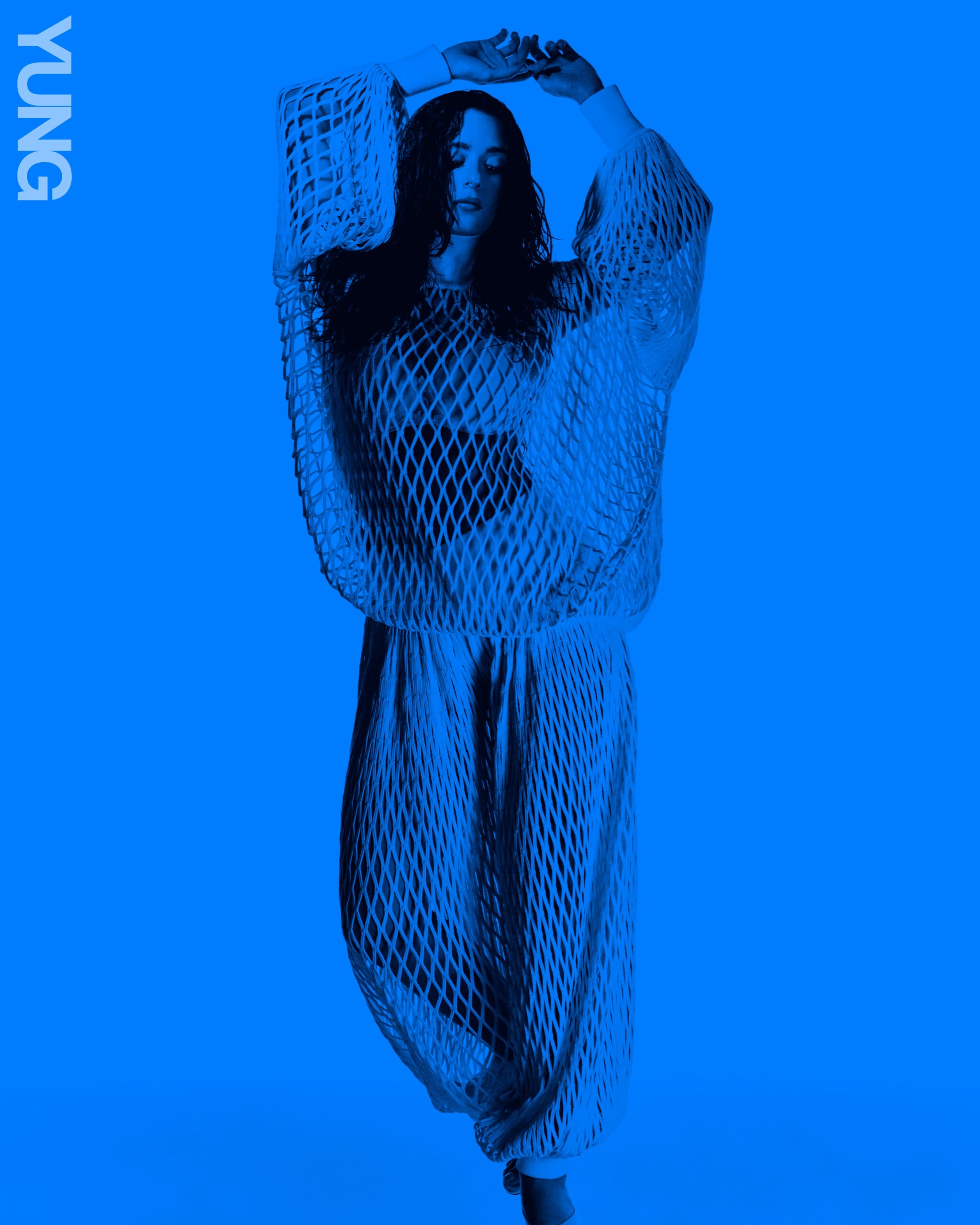

When Lebanese comedian Nataly Aukar (Instagram) takes the stage in New York, she brings with her a paradox: the sharp instincts of someone who’s always used humour to survive, and the deliberate, methodical writing of an artist who knows that pain isn’t always material. “I don’t believe everything needs to become a joke,” she says. “If I find something that’s funnier than sad to say about a subject, I’ll write a joke about it eventually… But I don’t try to push it if it’s not there.”

The Beirut-born comic fled Lebanon during the 2006 war, when she was just twelve years old. “It was my first time experiencing anger and confusion,” she remembers. “The sudden snatch out of the country, and away from everything and everyone I knew, at a time where internet and phones weren’t accessible to us, was painfully difficult.” The displacement marked her deeply, “I spent a year and a half in NY very angry, which is something my family still mocks me for”, but it also sparked the beginnings of a personal shift that would later emerge onstage.

Her humour is rooted in that contradiction: a love for Lebanon tempered by estrangement, an early desire to assimilate that now gives way to a refusal to explain herself. “Having had spent most of my life in Lebanon before permanently moving to NYC for comedy, I never questioned my identity and neither did the people around me. A Lebanese in Lebanon. That’s what I was,” she says. “And when I arrived here I suddenly didn’t look or sound as Arab as people thought I should? I struggled with my identity and felt like I always had to prove it or justify it. But eventually I stopped caring completely and just focused on me and my truth.”

There was no “aha” moment where Aukar realized comedy was her calling. It was always there, baked into the culture around her. “Honestly everybody [made me laugh]. Lebanese people are hilarious,” she says. “My dad was the first person that made me laugh… My mum is also very funny. Much drier and darker which I realize today is where my humour comes from. My grandparents are also hilarious. I’d spend a lot of time with them. I am obsessed with my maternal grandmother and grandfather.”

And then there were the teachers, “a little kookoo”, and the daily absurdities of life in Beirut. “Very little was taken seriously around us in the country. In a place where everything is constantly crumbling down, people know how to find joy.”

But joy has limits. The aftermath of the 2020 port explosion, for instance, is still something that’s beyond jokes. “I still see the pain of the port explosion in the faces of the people I love who were there that day,” she says. Even so, she doesn’t believe in keeping comedy too precious: “If there’s a point to it,” she adds, “I’ll write a joke about it eventually.”

Nataly Aukar doesn’t craft different sets for Arab or non-Arab audiences. “I make sure that I am always writing in a way that everyone will understand what I’m talking about. I don’t like alienating audiences or writing jokes that would only work for one and not the other,” she says. “I want to talk to both.”

Still, being Arab in America comes with its own calculus. She recalls a moment at summer camp, not long after arriving in the US, when a girl told her, “My country is at war with you.” “We had just got to NYC from the war in Lebanon and I was very scared, lonely and confused,” she says. “That’s when I started really learning English and trying to polish my American accent. So I can blend in. And I got so good at it now I don’t even know what my real accent is anymore.”

Nataly Aukar has said before that she wanted to “change everyone’s mind” about Lebanon through her work. Now she laughs at that younger self: “That is a crazy and unrealistic goal. That was my goal when I was first starting out in comedy and was still too naïve and too egotistical. I laugh at myself now for it.”

Still, she hasn’t abandoned the mission entirely. “I like to think that I can at least reshape the thoughts of one person per show and to me that counts for something in the butterfly effect. That’s why I like to perform in English. To reach the people who are not us.”

Her comedy doesn’t always land safely. When hecklers interrupt her set or the room turns political, she doesn’t have a one-size-fits-all response. “It depends on my mental state that day, and how the show is going to begin with,” she says. “Sometimes I’m tired and already not in the mood. So things can go south pretty fast. Oops.”

After nearly a decade in the business, her definition of success has changed. “Smaller than ever,” she says. “The more you seem to grow to others, the less you feel it yourself… Your own expectations of yourself get bigger, your real life gets further and further from the one you had envisioned for yourself and you constantly have to rewrite it all.”

That rewriting is where her work lives, in the in-between, the dark parts, the punchlines that take their time. “Comedy has helped a lot,” she says. “But I definitely stopped putting too much pressure on comedy to solve all of my pain and discomfort… It actually often makes dark times darker.”

Asked whether she considers her work a form of activism, she answers without hesitation: “Probably yes. It’s the only outlet I know how to communicate through. And I have a lot of feelings and opinions. So I sneak them all inside my jokes.”

If there’s one thing she hopes people walk away with after a show? It’s not a revelation. It’s a reality. “That I’m tired,” she deadpans, “and I’d rather be home watching TV in the dark.”

For more stories of art and culture, like this interview with Nataly Aukar, visit our dedicated archives.