“I’m not concerned as much with the project of visibility,” Safia Elhillo (Instagram) begins. “It’s not that I am talking about my communities to someone else—I’m talking to my communities, facing inward.”

The Sudanese-American poet’s work is not a megaphone broadcasting her heritage to an unknowing world. It is not a translation of the Sudanese-American experience for the uninitiated, but a celebration of shared cultural memory, a homecoming for those who recognize themselves in her words.

“I come from people who speak beautifully for themselves,” she asserts, “and don’t need me to do anything other than talk specifically about my own experience.”

Safia Elhillo eschews the mantle of ambassador, instead stitching together a lyrical mosaic of “specific references and image systems” that resonate with the shared cultural memory of those who, like her, straddle the worlds of Sudan and America. She is not a spokesperson for a monolithic Sudanese-American experience, but rather a cartographer of the nuanced and often-overlooked nuances of identity, belonging, and cultural hybridity.

In Elhillo’s poetic universe, language is a playground, a space where English and Arabic dance and intertwine, where a “hybrid invented language” flourishes, both reflecting and shaping the unique contours of their collective identity. “What I’m trying to do in poems that have both English and Arabic text in them,” she explains, “is just trying to depict, as directly as possible, the way that language actually works in my head.” Language, in Elhillo’s hands, is a fluid entity, a shape-shifting creature, mirroring the multifaceted nature of her own identity. “Those are the only situations where I don’t feel like I’m translating one to another because each word comes out in whatever language I thought it in,” she explains. It is in this liminal space, this cultural in-between, this linguistic crossroads, that Elhillo finds her most authentic expression.

“A not-uncommon symptom of my diasporic upbringing is the privilege and wound of bilingualism,” she reflects. “I have access to the two versions of the world that the two different languages contain, but I’m also never going to be entirely fluent in either because part of me will always belong to the other one.”

The specter of conflict, however, looms large in Elhillo’s consciousness. The ongoing conflict in Sudan casts a long shadow, informing her work. Yet, she refuses to succumb to despair, drawing inspiration from Toni Morrison’s clarion call: “This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

In “The January Children,” her debut collection, Safia Elhillo delves into the complexities of displacement and longing, her poems shimmering with the ghosts of a homeland left behind. Through the lens of nostalgia, she explores her own “Arabized Africanness/ Arabophone Blackness,” an identity that challenges the rigid boundaries of race and ethnicity. The poems are infused with the rhythms of Sudanese music and the fragrant spices of childhood memories, creating a sensory landscape that is both familiar and foreign, intimate and universal. “I don’t want it to be a lifelong habit of mine to only write about Sudan in past tense, as if it’s gone or lost, as if I didn’t have a life there,” she muses. “I think these days, because of the war, I am mourning all the time I spent looking backwards at a time before mine, instead of relishing the present tense, the actual Sudan I did have.”

Poetry, for Elhillo, is not a mere vocation but a lifeline, a means of navigating the turbulent waters of the human experience. It is a playground for curiosity and experimentation, a sanctuary where she can unravel the threads of trauma and weave them into something beautiful and new. While she once used poetry as a tool for processing trauma, she has since shifted her focus. “Now I am driven mostly by curiosity, by experimentation, by play,” she reveals. “The space to work out my hurt and trauma cannot be the space where I am doing my work.”

In her novel in verse, “Home Is Not a Country,” Safia Elhillo continued her exploration of the elusive concept of belonging. “For so long, nations and nationality were so central to my crisis of identity,” she confesses, “and eventually I just got bored of that and how it hurt me.” Instead, she embraces a more fluid and expansive definition of home, one that is rooted in community, shared experiences, and the ever-present possibility of reinvention. “My mother often says ‘I made home’ and I love that—the idea that home is not a ready-made location…but rather it’s an active construction,” she explains.

For Elhillo, home is not a fixed point on a map, but a constellation of interconnected experiences woven from threads of love, memory, and cultural heritage. It is a fluid concept, a “portable environment,” a “decision, a project,” constantly evolving and expanding, shaped by the intricate dance between the individual and the collective. “I got it into my head that everything would feel better if only I could figure out where I was from,” she reflects. “In that fixation and obsession, I failed to appreciate and acknowledge the ways I did belong.”

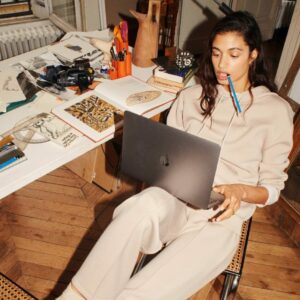

Elhillo’s poetic process is as eclectic and multifaceted as her identity. She writes in bed, on her phone, in stolen moments between the demands of a “made-up” job that encompasses everything from commissioned poems to teaching gigs. Her annual 30/30 challenge, where she writes a poem a day for 30 days with friends underlines the power of community and the importance of accountability in the creative process. “I am trying to create systems for myself, not for forcing myself to write when I don’t want to, but rather around the fact that usually I badly want to write and then I don’t,” she confesses. This raw honesty, this willingness to embrace the messy realities of the creative process, is perhaps the most endearing aspect of Elhillo’s work.

Safia Elhillo’s poetry is a gift, a kaleidoscope of language, memory, and cultural identity. Her words, like a gentle breeze, carry us across continents and through time, reminding us that home is not a place but a feeling, a state of being that we create and nurture within ourselves – a celebration of the beauty that can be found in the in-between spaces.

Her words are an invitation, a challenge, and a celebration of the infinite possibilities that lie within us all.

For more stories from the MENA diaspora, like this of Safia Elhillo, head to our dedicated Arts & Culture coverage here.