In the heart of Doha, an ambitious exhibition is challenging how we view Orientalism—both as a historical art movement and as a contemporary dialogue. Orientalism, as defined by scholar Edward Said, refers to the Western depiction and representation of the “East”—its cultures, people, and landscapes—often steeped in stereotypes and colonial attitudes. It is both an aesthetic and a worldview, one that has historically exoticised and othered the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia. Titled Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme, the showcase at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art (Instagram) is an evocative convergence of the past and present. Through the work of 25 artists, the exhibition dares to ask: how does Orientalism continue to evolve in today’s interconnected and, at times, fractured world?

At its core are the works of Jean-Léon Gérôme, a 19th-century French artist whose exquisite and controversial portrayals of the “Orient” have long been at the centre of debate. With approximately 400 pieces on display, the exhibition dissects Gérôme’s influence, his romanticised depictions, and their lingering impact on perceptions of the Middle East and North Africa. Yet, this is far from a retrospective—it is a conversation, a clash, a reckoning.

Surrounding Gérôme’s storied works are contributions from 25 contemporary artists, each offering their own perspective on Orientalism’s enduring legacy. These pieces do not merely critique; they challenge, reinterpret, and reclaim. Iranian-British artist Farhad Ahrarnia employs khatamkari, an intricate Persian marquetry technique, to create a vibrant dialogue between Eastern tradition and Soviet modernism. His work reflects the layered identities and global influences that Orientalism often overlooks.

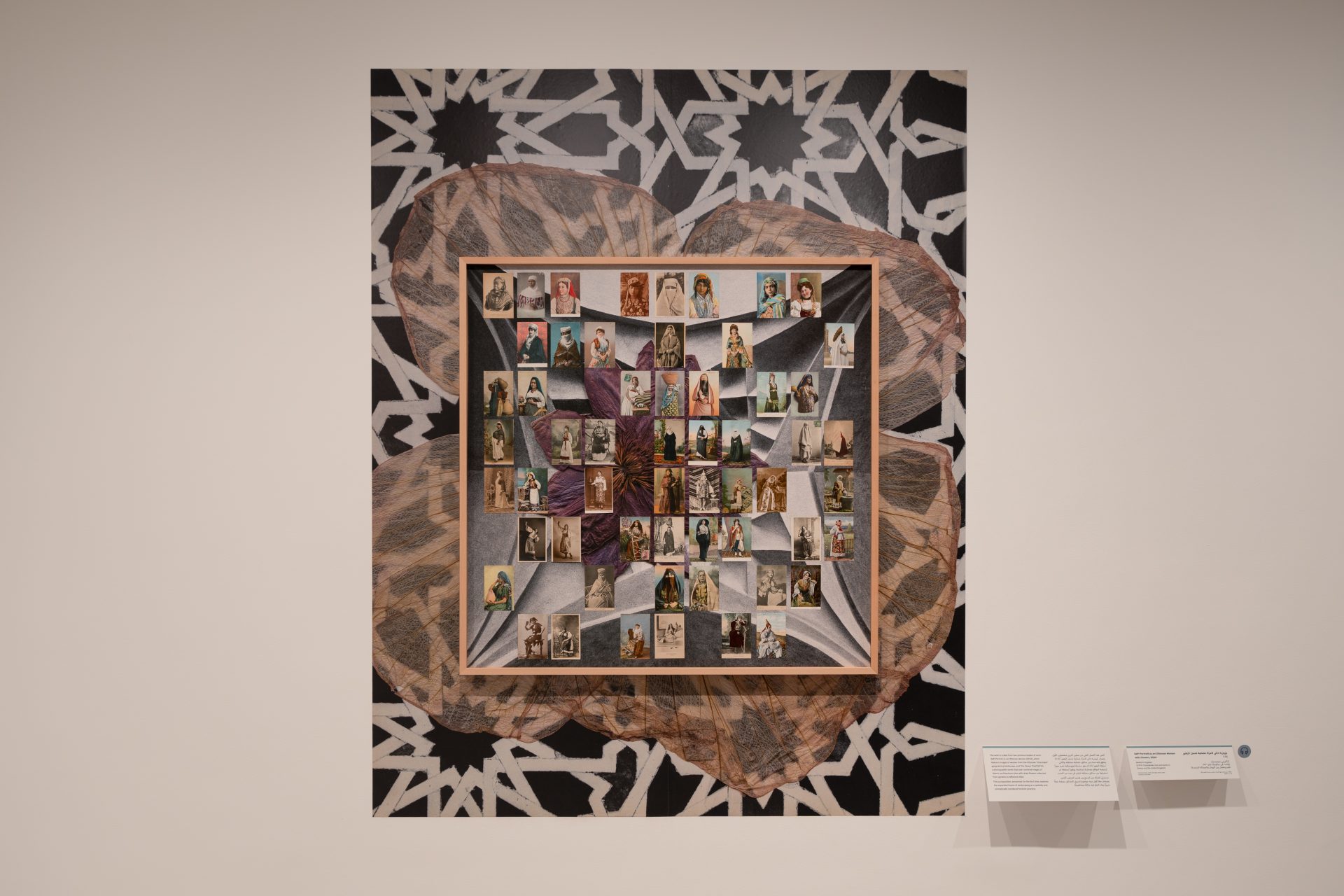

Then there’s Aikaterini Gegisian, whose Self-Portrait as an Ottoman Woman with Flowers combines archival postcards, dried flora, and Islamic architectural motifs. Her feminist lens fractures the male gaze that has historically dominated the narrative, offering a poignant and visually stunning counterargument.

Perhaps the most visceral contribution comes from Tunisian-Ukrainian artist Nadia Kaabi-Linke, whose installation, One Olive Tree Garden, features a concrete-cast olive tree dissected into slices. Visitors must navigate through its fragments, a journey that mirrors the dissection of Orientalism itself—layer by layer, assumption by assumption.

What makes Seeing is Believing particularly compelling is its ability to transform the museum space into a site of reflection. It invites viewers not only to scrutinise the past but to question the ways in which Orientalism persists in modern imagery, media, and even tourism. The juxtaposition of Gérôme’s sumptuous fantasies with the raw, cerebral works of contemporary artists underscores a crucial truth: Orientalism is not confined to history books. It lives on, often subtly, in the ways cultures are commodified and consumed.

This exhibition, a collaboration between Mathaf and the future Lusail Museum, exemplifies Qatar’s dedication to fostering cultural dialogue. It isn’t just about looking back; it’s about moving forward, guided by a more nuanced understanding of art and identity.

For those in Doha—or those seeking a reason to visit—Seeing is Believing is not to be missed. It’s a timely reminder that art has the power to confront and transform, offering not just a window to the past but a mirror to the present.

Seeing is Believing: The Art and Influence of Gérôme will be on show until 22 February.

For more stories of art and culture, visit our arts and culture archives.