How do you feel that fashion can impact politics?

Fashion influences politics in a variety of ways, because at the end of it fashion is a mirror held up to society. Shirts, for example, have long been used as sites for resistance – they are the easiest way for a group of people to be seen as a collective whole. I look at women of the Black Sash, who wore a black sash across their chests to showcase the solidarity they had with minorities. That sash became an extremely politicised object, getting banned by South African police at some point. To challenge this, members of the Black Sash then started wearing long gloves and walking around with their hand across their chest. This illustrates just how powerful a message fashion can take.

Fashion can also indicate a socio-political and economic climate. Look at how after times of war and stress [1920’s or 2020], fashion tends to become more extreme and campy, almost as an overcorrection. Tough economic times tend to have more minimalistic fashion. The industry can be a reflection when read correctly.

Also, at its most basic, politicians use fashion to prop themselves up, to command respect and awe. It’s a funny thing, fashion can allow you to become anyone you want to be – it’s an armour.

Have responses to any of your collections ever changed your opinion of the theme that inspired them in the first place?

This hasn’t happened yet because, really, the collections aren’t a beginning, middle and end – there is space for reinterpretation and even critique. I find that the collections expose an idea, but a conclusion isn’t really imposed. It’s like being educated on something – you can learn its basic structure, its premise and everything else, but ultimately you must form an opinion of it and apply it to your own life, context and understanding.

Which of your collections make you most proud?

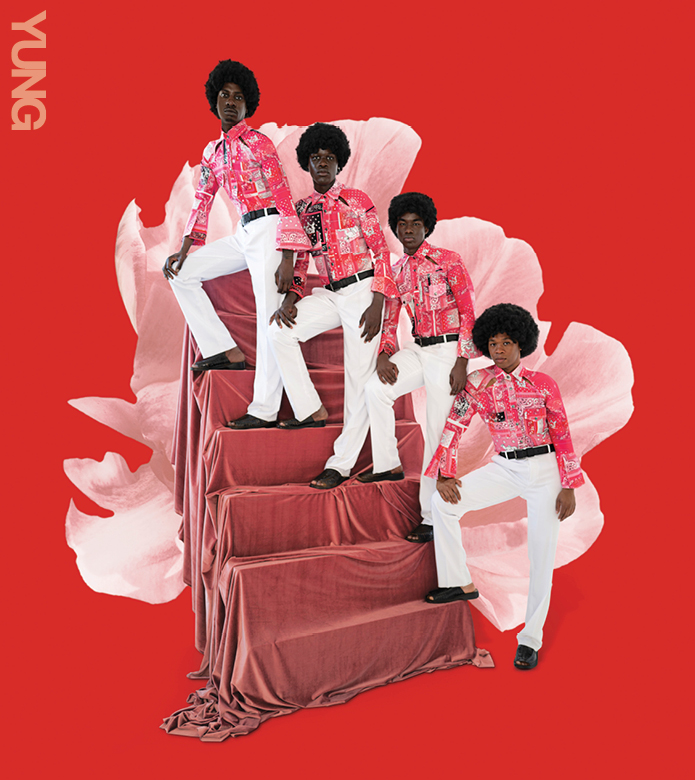

This is quite a challenging question because each collection has its own pace and intention. However, SS/22’s Genealogy collection was quite special to me. I admittedly had been quite miserable at the time. It’s impossible to ignore what is peak weltschmerz and, as creative people, we tend to subconsciously transcribe whatever hangs in the air into output. That season, I wanted to disengage with mounting pressures of having to create work that considers and reflects the times and to create a personal body of work that, even if niche, looks inwards at the part of my life that always gets me through: my family.

Set-up as a roundtable discussion, Iris Magugu, my mother, and Esther Magugu, my aunt , proceeded to unpack a box of family photos which illustrate significant moments in all our upbringings. The brand has always cited very specific references and motifs, which were all chronicled and broken down in that documentary. The collection pickpockets a variety of eras: my grandmothers masterfully pleated skirts and draped blouses from the 1950’s, my mothers leg-of-mutton sleeves from the 1960’s, and her subsequent rebellion in the 1970’s with improbably short skirts, which my family in jest refers to as her ‘two centimetre clothes’ era. In the ’80’s, my aunt Esther experimented with localised punk, inspired by the rising star of that time Brenda Fassie, who Time magazine had just named The Madonna of the Township. All these women, living under the same house, sharing and workshopping clothes out of necessity, each developed an interesting and hybridised sense of style, which could oscillate from 1990’s Stealth Wealth to 1890’s Devotion.

You’re quite outspoken (via your collections) on various injustices in South Africa. Has there ever been a backlash to this?

It’s always been quite positive. The brand addresses politics that might be specific to South Africa but I think everyone across the globe can relate to at least one element of the story. For example, the SS/22 collection deals with very specific photos from the past but the idea of family is a universal one. AW/21 was about African Healers but the idea of spirituality is a universal one. SS/21 looked at South African spies but the idea of espionage is one that fascinates the world all over.

It does become incredibly difficult for me as an individual though. I completely understand its place as a fashion brand that needs to think for and represent others. But it’s using the collections as a way to tell stories that run the risk of being forgotten – some good, some bad – that I am personally fascinated in. It’s a tricky balancing act between myself as a brand and myself as an artist.

Finally, what has been your most memorable experience?

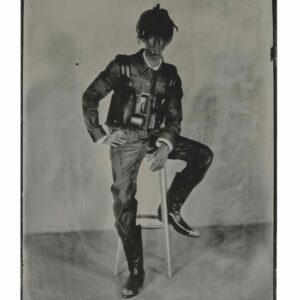

Creating my current collection was quite memorable. I’ve been rummaging through a lot of discarded clothing at Dunusa, an area in downtown Johannesburg where America and Europe dump piles of second-hand, often soiled garments. It got me thinking about globalisation’s effect on national stylistic identity. It’s not rare to see a local woman wearing a traditional shweshwe-fabric waxed wrap skirt, often reserved for special ceremonies, paired with a promotional Vodaphone or Manchester United polyester tee. This hybridity – an unintentional dialogue between ‘The West and The Rest’ – was the start point of this collection. I subverted ideas from Thorstein Veblen’s 1899 essay “The Theory of the Leisure Class” and the collection experiments with the idea of a ‘trickle-up fashion theory’, instead of the trickle-down version discussed by Veblen, which argues that fashion starts with the bourgeoisie and makes its way down the classes, eventually ending up in places such as Dunusa.

With SS/23, I was interested in how Dunusa can shoot items considered ‘old hat’ back up into a luxury space. The collection was built by sourcing discarded clothing at Dunusa, bringing it into the studio, where I analysed silhouettes and proportions, cut into them to expand, then refashioned them in updated materials. There is a ‘soft decay’ about the collection from a design POV, as if once magnificent clothing is seeing the early stages of damage. Fraying appliqué, gashes of slits and pleated skirts that seem torn into are motifs that communicate the season’s direction.The 20-look collection also has an associating 15 minute process documentary I shot in downtown Johannesburg on site at Dunusa and at my studios.