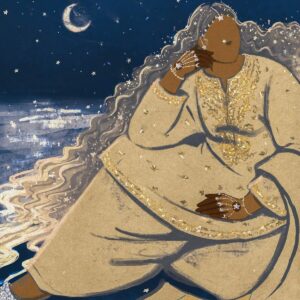

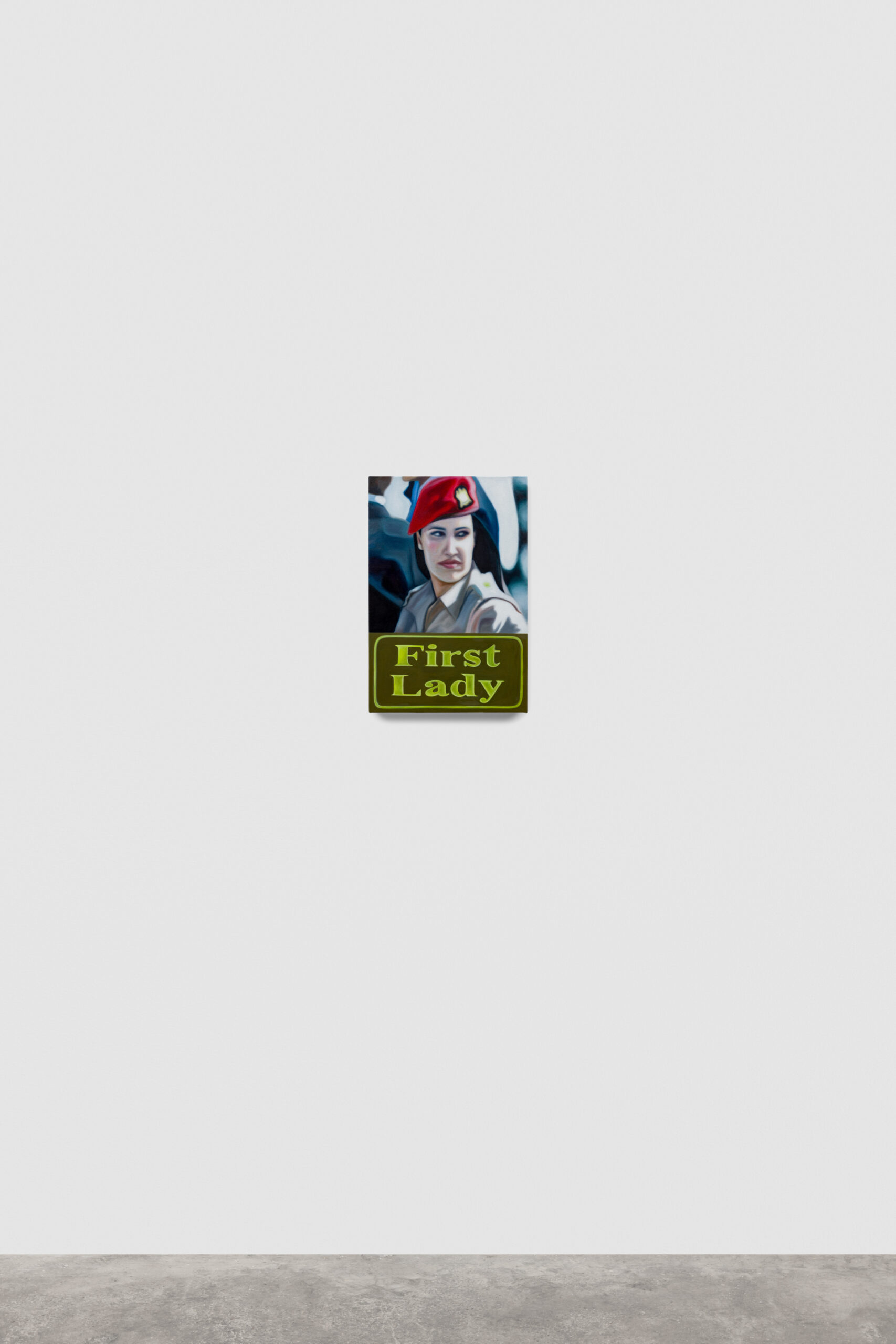

Tasneem Sarkez (Instagram) a Brooklyn-based artist and NYU graduate, is gaining recognition for her “Arab kitsch” style, a vibrant blend of pop culture, symbolism, and diaspora nostalgia. Born to Libyan parents in post-9/11 America, she offers a Gen Z perspective on anti-colonial narratives and internet culture. Her art seamlessly merges cultural heritage with personal and collective memory, drawing inspiration from history, social issues, and her Arab diaspora experience. Sarkez’s storytelling and reimagining of cultural memory push boundaries, transforming everyday imagery into striking, thought-provoking art that resonates with a generation connected to its roots while navigating a globalized world.

What initially drew you to art, and when did you realise it would become your primary focus?

Art has been a part of my life from a young age. It’s something that’s been the most intuitive aspect of my life. And that intuition has felt more focused in recent years, but if I had to pinpoint a singular moment it would be the trip I took to Morocco in 2018. It was my first time traveling alone, and I was there for a month and half. I learned a lot about myself and one of those things was how much I cared to have art in my life. I haven’t been the same since.

Your work is deeply rooted in identity and cultural materiality. How did growing up in Portland, being an Arab, influence your artistic perspective?

The Arab community is quite small in Portland, so I think seeking that sense of community in relationship to art influenced my perspective on the contemporaneity of it all, with my interest in the internet, the digital, memes, et cetera, all while finding these “pockets” of home–as a feeling.

How has studying at NYU shaped your approach to art, and what has been the most valuable lesson you’ve learned?

I initially didn’t plan to go to school for Art, which is funny to think about now. I was set to be a psychologist. So I think to immerse myself fully in a school that is centred around all kinds of art, while still having a liberal arts education, positioned me to have more of a well-rounded academic background in art, than just a literal studio practice. Which is something that I didn’t want to lose in studying art. So overall it made me more sensible to the amalgam of what I’ve learned, and how that finds itself into my praxis. I’ve really developed a routine of research and studio practice during university that works for me, and still is my everyday routine.

Your work explores the “translational abstraction of Arabness.” How do you define this term in relation to your art?

When we think of our senses and how we react to the idea of publicness, it’s not just a literal understanding of where we position ourselves in physical environments, but also in the metaphorical conceptions of collective thought and language that influence us beyond a tangible level. To play with the boundaries of private and public within my work, to signify cultural semiotics subtly, or even loudly, it’s very dynamic for me. My work develops a translational abstraction of identity and its self-conception that resides in the alternative of that. And that is where the work resides. In that abstract idea of tension.

Your book Ayonha was acquired by the Met’s library. How does working in print and archiving connect to your larger artistic practice?

I’m a collector of many things. My work in print is just an extension of that obsession I have, to see the physicality of culture and the things I’m excited by. I’m influenced by books of all sorts – art, photography, essays, poetry, et cetera, and I like to surround myself with them. There’s a longevity to books in archiving that is a bit different than paintings and sculpture. It’s more accessible as a material to understand, and can travel with you. I can carry a book around every day in my bag, but not a painting, you know. It’s that sentiment with archiving that is important to keep histories alive by documenting them.

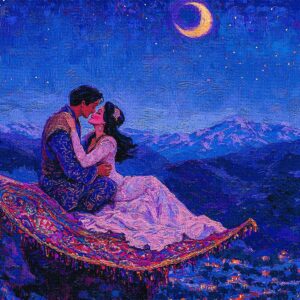

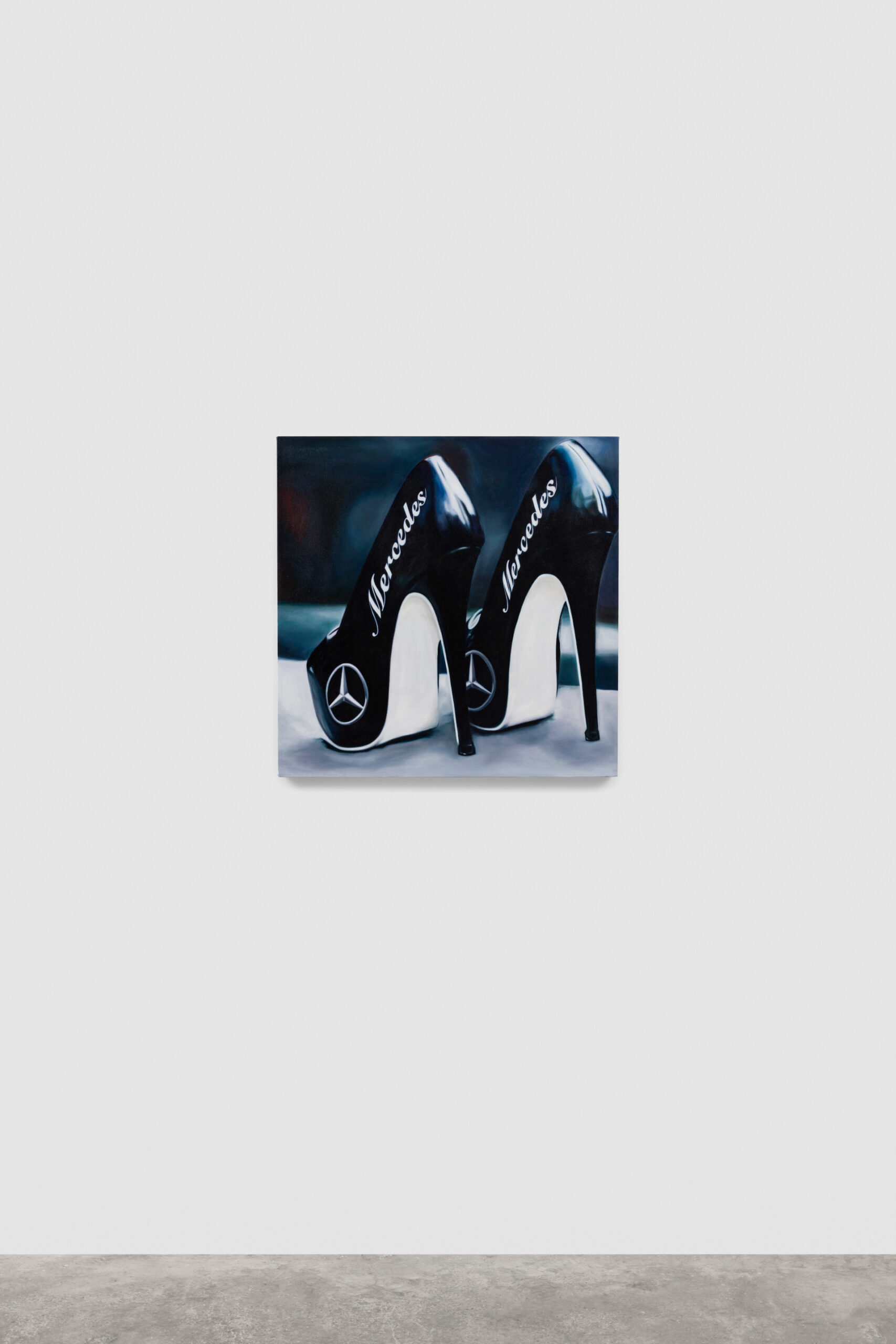

You incorporate memes and pop culture into your work, such as the Calvin-Gaddafi image. What role does internet culture play in your artistic language?

Internet culture informs the methodology of the work. How I compose a painting in terms of form, or choose a particular font, a colour, the cropping of the image – that shared lexicon that exists between art and internet informs how I relay the message to the audience. And in turn the audience can place itself into the modernity of how we come to understand images. It’s really about language and thinking how much technology has adapted with us as a society. That word “Technology” originated in a time where we used that to define the idea of craft and its methods’. So I think we’ve adapted to technology both in terms of society and linguistically and that impacts the readability and legibility of art, photos, and reality, to where we are very comfortable to identify a photo as a “meme” just off of its merits.

If your art could have a conversation with you, what do you think it would say?

Good Morning.

For more stories of art and culture from across the region and the diaspora, visit our dedicated archives.