Me: Must stay informed, must read everything. Also me: Muted every news app, watching cat tarot on TikTok instead.

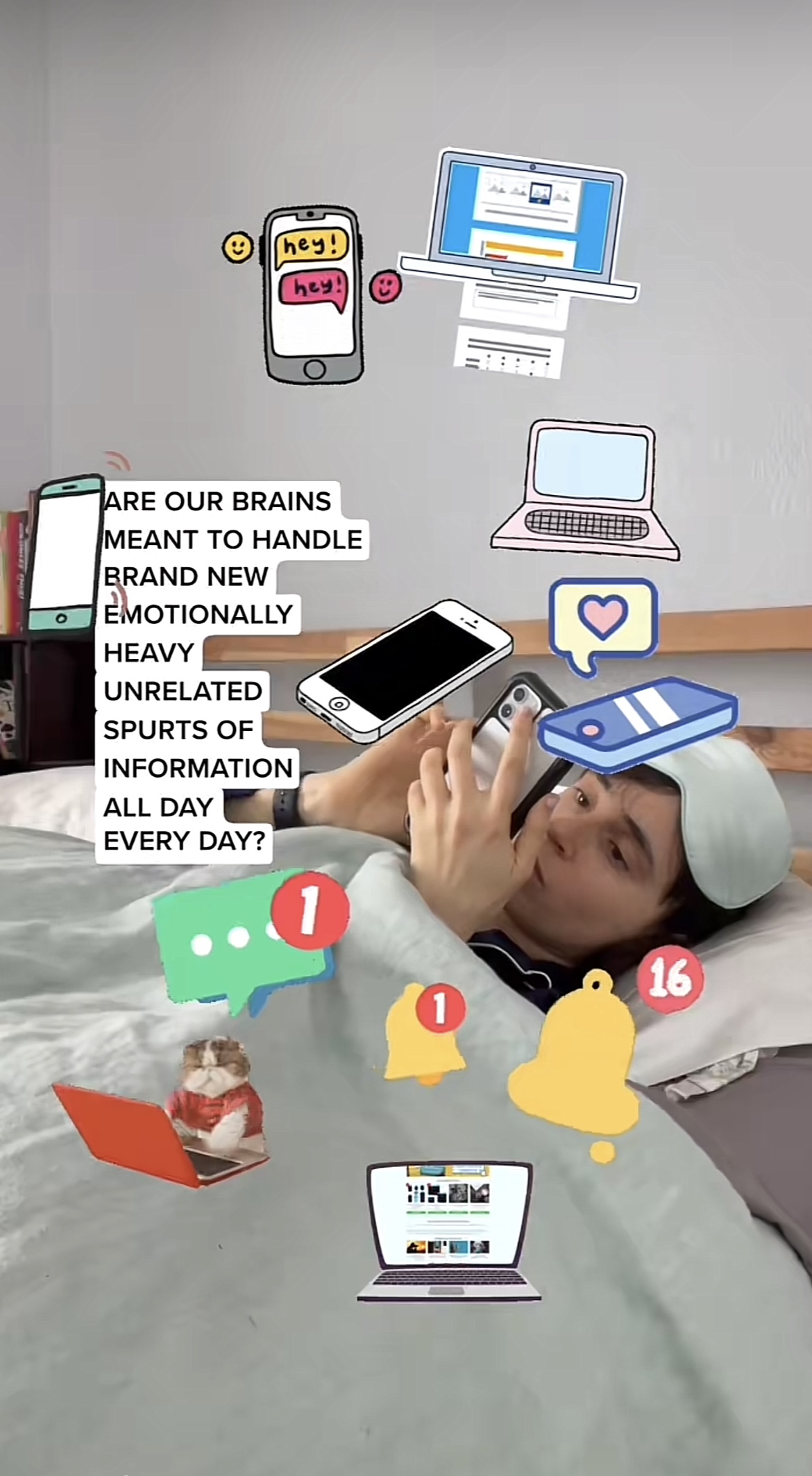

If knowledge was once power, today it feels more like quicksand. Between the algorithm’s infinite buffet of content and a news cycle that never sleeps, young people are taking in more information in a single day than their parents might have processed in a week. But instead of enlightenment, the result is usually exhaustion. Every headline competes for outrage, every outfit choice is politically coded, every post feels like a statement. Being online now means carrying the weight of knowing too much… and not knowing what to do with it.

The ways Gen Z copes with this overload are as inventive as they are contradictory. Some lean into ironic detachment: memes that joke about the end of the world, TikToks that make doomscrolling feel communal. Others flirt with self-imposed ignorance, muting keywords, swapping out the news app for astrology charts, or going offline altogether under the guise of a “digital detox.” For many, ignorance isn’t apathy; it’s survival.

A 2024 Suez University study among Egyptian college students by Ms. Abir Ahmed Tolba found that social media fatigue is strongly linked to anxiety, stress, and depression. Students who spent more time scrolling or engaging with feeds (skimming, commenting, watching stories) reported significantly higher levels of mental exhaustion. In Saudi Arabia, a 2024 online cross-sectional study of 2,856 adolescents (ages 10–24) revealed that 77.4% of participants have tried to reduce their social media use for mental health reasons. Many reported that social media disrupts their sleep: 71% said excessive use negatively affected sleep patterns.

And in the UAE, a 2020 policy paper “Media and Information Literacy Among Millennials and Generation Z in the Arab World” highlighted that young people are good at navigating multiple forms of media, but many lack strong critical evaluation skills. For example, they struggle with distinguishing reliable vs. unreliable information, which increases vulnerability to misinformation and contributes to overload.

Circling back to Egypt, the phenomenon of news avoidance is growing. A recent AUC mixed-methods study (surveys and interviews) found that news overload is one of the strongest predictors for people intentionally disengaging from news. When the headlines are constant, repetitive, or feel unreliable, many young people simply choose not to follow them.

What’s also emerging across the region are new ways to tackle digital wellbeing. In Saudi Arabia, Ithra’s Sync initiative, developed with international partners, is piloting programs that make sense within local routines, from school workshops to family-focused tools. It reflects a growing recognition that global “screen time” advice doesn’t always fit; cultural and social contexts matter.

Coping has become its own kind of content. On TikTok, “hot girl walks,” “silent reading parties,” and “bed rotting” are dressed up as lifestyle hacks, while trends like “de-influencing” and “digital minimalism” attempt to make unplugging feel aspirational. Self-care has turned into self-branding, transforming rest into reels, or reframing discipline as an aesthetic. Even healing becomes shareable. The irony is that while these trends promise escape from digital saturation, they also just repackage it into another feed-friendly cycle.

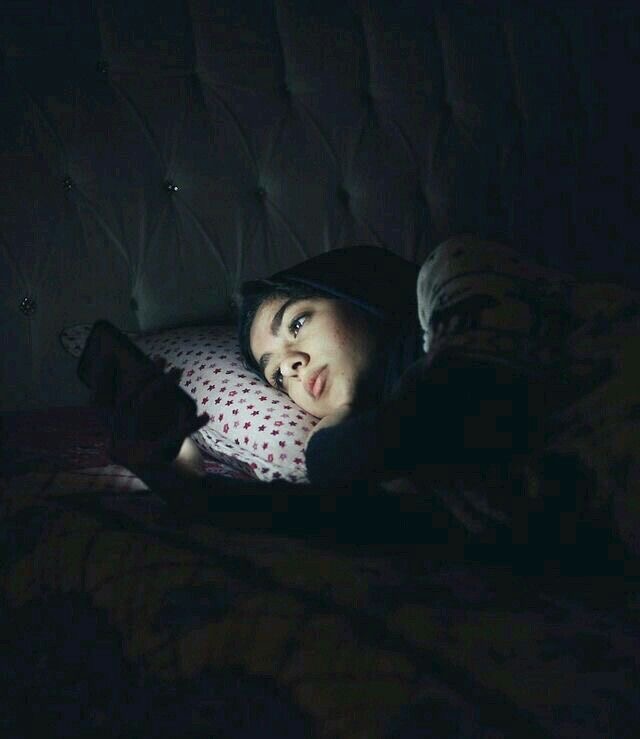

At the same time, Gen Z knows there’s no true exit ramp. Work happens in Slack and WhatsApp, activism unfolds on Instagram stories, even friendships and dating rely on constant pings. The very tools that drain us are also the ones that connect us. The fact of the matter is, in this day and age, there’s no escaping. That’s why even rest tends to be mediated by screens; whether it’s doomscrolling in bed or zoning out with YouTube white noise playing in the background. The paradox is clear: we crave disconnection but fear irrelevance, so we learn to live in a state of half-presence, toggling between overexposure and withdrawal without ever fully leaving the feed.

Still, there’s a cost to filtering so much so often. Knowing everything can make us feel smarter, sure, but it also makes us anxious, defensive, perpetually over stimulated. At the same time, not knowing feels like a risk in itself; a missed chance to act, to belong, to be on the right side of history (or at least the group chat). What emerges is a generational balancing act: walking the line between being informed and being consumed. That’s the real lesson of living inside the feed; not how much we can know, but how much we can let go.

For more stories of culture, visit our dedicated pages and follow us on Instagram.