When American Eagle revealed its latest ad campaign starring American actress Sydney Sweeney, it didn’t just lean into Americana — it doubled down on coded beauty ideals. The campaign hinges on a wordplay between “jeans” and “genes,” using Sweeney’s face to suggest she’s simply built differently. What might have once passed as cheeky now feels insidious, showing a side of fashion marketing that still clings to exclusionary ideals with genetic roots.

The fashion and beauty industries have long upheld a narrow ideal: thin, white, cis, able-bodied, symmetrical. The ads might change their colour palette, but the face remains the same. It’s easy to think of beauty marketing as shallow — a parade of faces, figures, and filtered ideals. But what if the standards it sells are not just superficial, but structural? What if this familiar image of “natural” beauty is less about taste and more about history — a history firmly based in control?

At its core, eugenics was a pseudoscientific movement that emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, stuck in the belief that society could be improved by “engineering” better human beings. That meant encouraging those with “desirable traits” — whiteness, able-bodiedness, heterosexuality, intelligence (as narrowly defined by white Western standards) — to reproduce, all whilst actively preventing or discouraging those with “undesirable” traits from having children.

Governments around the world, from the U.S. to Germany to Scandinavia, implemented forced sterilisations, banned interracial marriage, and created hierarchies of genetic worthiness. Eugenics was used to justify some of the most violent systems of control in modern history, from institutionalising disabled people to laying the groundwork for the Holocaust. While today’s society largely disavows eugenics in name, its aesthetic legacy lives on — in ways that are more insidious, because they’re harder to see.

When a campaign like American Eagle’s leans into language like “great genes” and casts a face like Sydney Sweeney’s to embody that concept, it isn’t neutral. It’s an aesthetic call-back to decades of messaging that has privileged whiteness, class, and so-called “genetic superiority” — only now, it’s dressed in size-6 denim.

The backlash on social media was swift. Viewers called out the ad’s unsettling glorification of inherited “white” beauty, and the fact that the brand is selling a fantasy of biological superiority. The sentiment echoed wasn’t just that American Eagle got it wrong. It was that someone like Sydney Sweeney — with her white features, blue eyes, and blonde “greatness” — would always be cast in a campaign like this. Because people of colour — Black, Arab, South Asian — are still rarely seen as having “great genes.” In the unspoken racial hierarchy of global beauty marketing, our traits are rarely viewed as aspirational. We’re often too much of something — too textured, too dark, too ethnic — or just not enough.

It wasn’t just the concept that was misguided, it was the timing in an era where audiences are calling for genuine inclusivity, and there’s an escalation of racial violence, rising ethnonationalism, and the politics of belonging. At a time when Latinos are being pulled from their homes by ICE, Arabs are still being racially profiled in airports, and Palestinians are still fighting to be seen as human in global media, the messaging felt tone-deaf at best — sinister at worst. Amidst all of this, American Eagle served up a genetically blessed blonde girl in a campaign that seemed to say: beauty runs in the bloodline, and you’re either born with it or not.

Trump-era America made it clear: whose genes are valued, and whose are criminalised. The echoes of that logic haven’t disappeared — they’ve just become more aesthetic. Beauty, in this context, becomes another border. One that separates the “great” faces from the rest. One that celebrates whiteness not just as a look, but as a lineage. In this narrative, there’s no room for a nose like yours, or a surname like yours, or a history like yours.

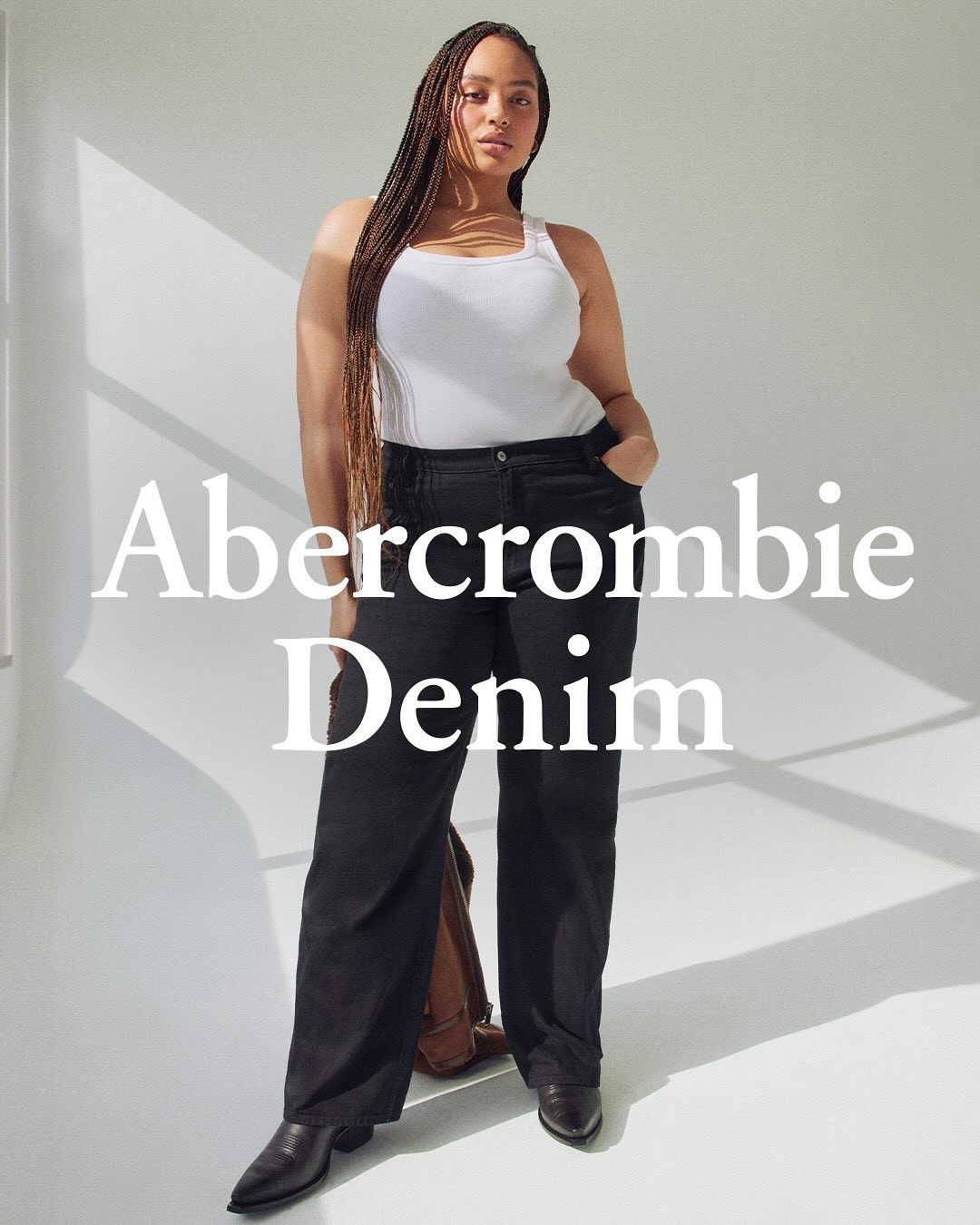

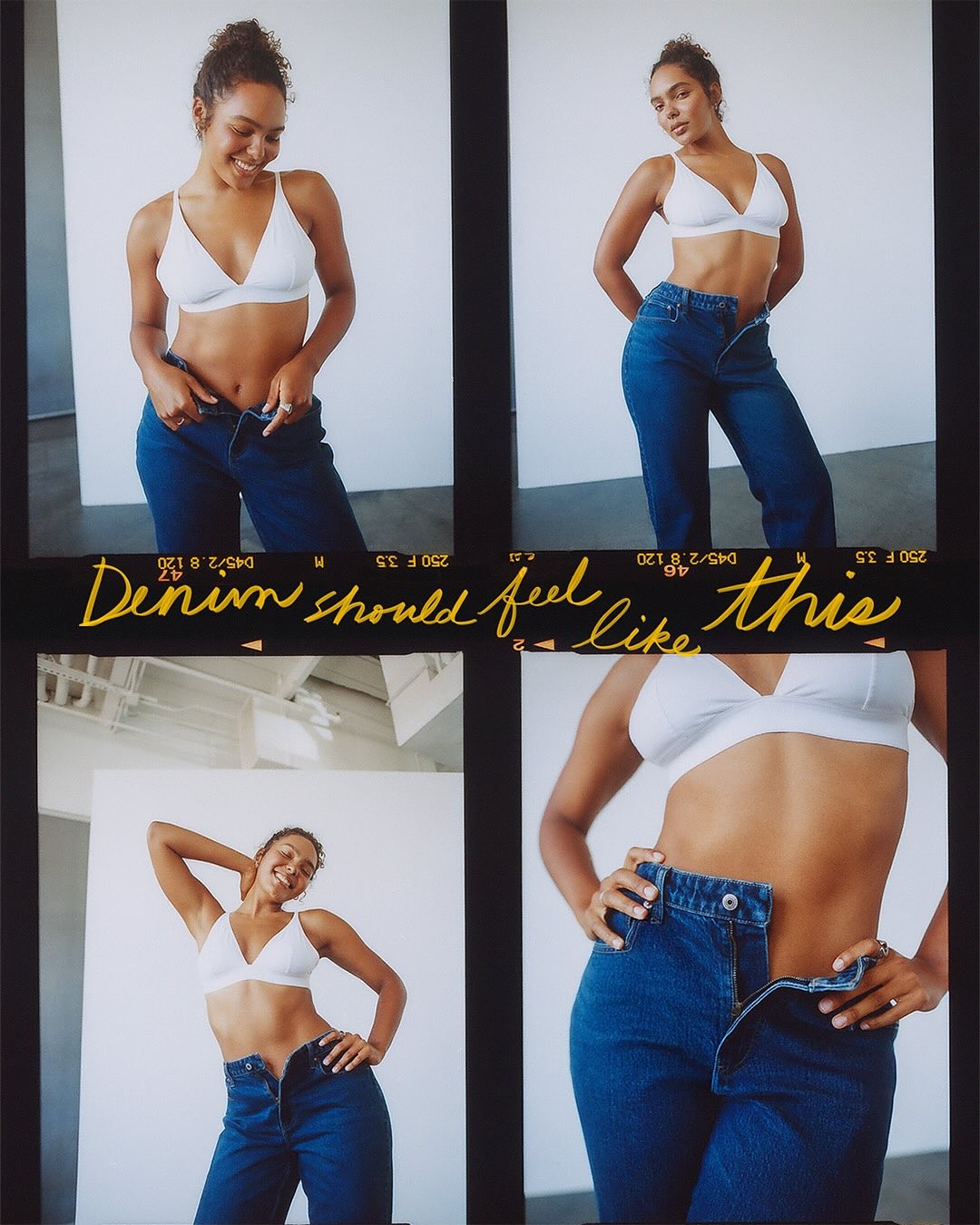

While American Eagle clings to outdated beauty codes, Abercrombie & Fitch seems to have clocked the shift. Just days after Sydney Sweeney’s “genetic beauty” campaign went viral for all the wrong reasons, Abercrombie rolled out a denim campaign that felt like an antidote. It featured a range of models with different body types, skin tones, and hair textures—showing, not telling, what inclusivity actually looks like. Comments under the posts read like public applause: “This is how an ad is executed,” “Thank you for having diverse models!” and “This is what a denim campaign should look like.” (And Abercrombie themselves liked these comments on their Instagram). Right now, brands aren’t just being judged by the models they cast, but by the way they respond when their audience speaks.

Once the poster child for exclusion, Abercrombie & Fitch has undergone a full 180. The brand that once only hired thin, conventionally attractive (and mostly white) staff, refused to stock plus sizes for women, and built its image on shirtless models with six-packs, is now rebranding as radically inclusive. Back in 2006, then-CEO Mike Jeffries even stated outright that Abercrombie was only for “cool, good-looking people.” That statement — and the hiring discrimination lawsuits that followed — cemented the brand’s elitist reputation. But now, years (and one Netflix documentary) later, the aesthetic of polished prep has been cracked open and reassembled with a new ethos: one that trades exclusivity for relatability.

Big, global brands don’t operate in silos. Their campaigns set the benchmark. They create templates — visual, aspirational, and ideological — that are mimicked by regional brands trying to emulate success. In the Middle East, that mimicry manifests in casting choices: the same handful of racially ambiguous, light-skinned, often Eastern European models — many of whom are Ukrainian or Russian — appearing across fashion, skincare, and perfume campaigns.

It’s a cycle that favours imported faces over local ones, reinforcing the idea that beauty is something that arrives from abroad, airbrushed and already approved. Even when regional brands attempt inclusivity, it’s usually surface-level; like a shoot in Jordan or Jeddah that still centres non-Arab talent. This isn’t just a Western problem. It’s a symptom of a wider industry still addicted to control, to exclusion, and to inherited ideals of who gets to be visible, desirable, and profitable.

For more stories of fashion, local and international, visit our dedicated archives and get across our Instagram.