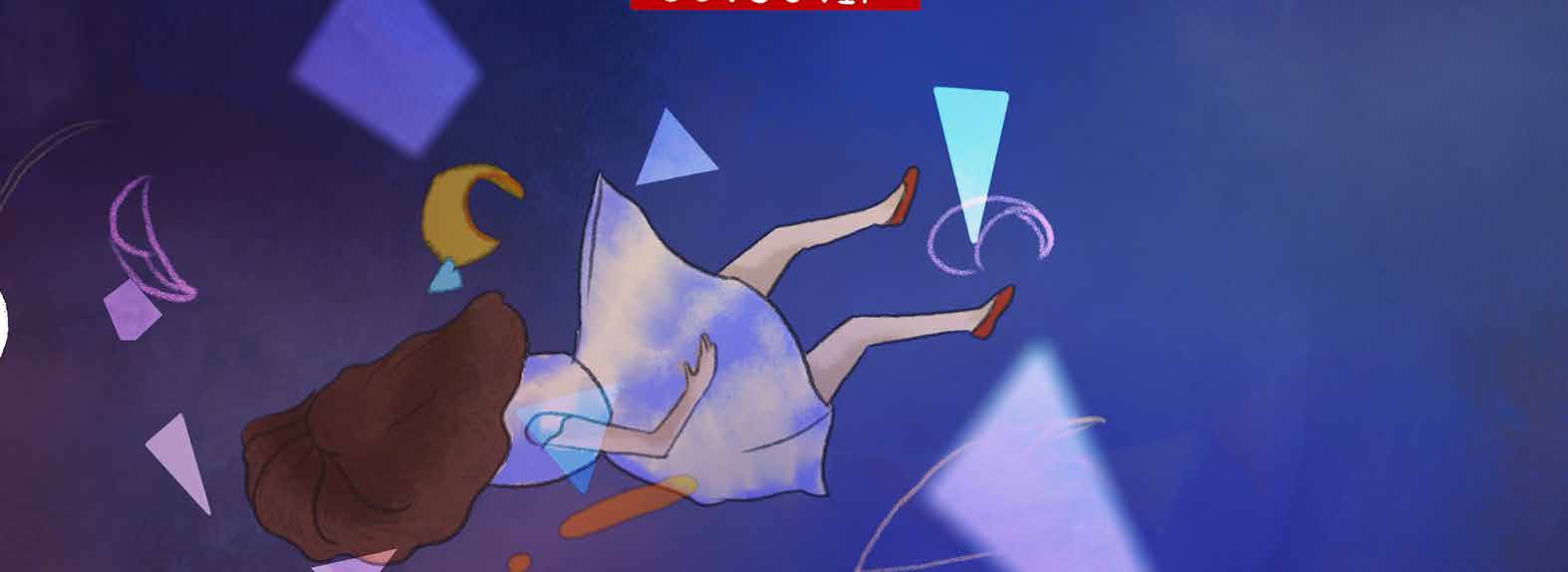

In their short animated film, “Peek-A-Boom,” Maya Zankoul and Toni Yammine confront the trauma of Beirut’s 2020 explosion through the innocent lens of a young girl, Mira. As director Maya Zankoul shares, “We wanted to show the idea of transgenerational trauma: the old version of Mira is inspired by my grandmother who lived through so much violence in her lifetime in Lebanon and is still traumatized from it today. These aren’t things you ever get over.”

“Peek-A-Boom” explores the intersection of personal and collective pain with a captivating blend of animation and storytelling. It takes the fleeting headlines of news cycles and humanizes them, creating a connection that lingers long after the credits roll.

Can you take us back to the moment when the idea for this film first germinated? How did it feel to decide to take on such a massive and personal subject matter?

I still remember the moment very clearly. It was about a week after the August 4 blast, and I was pregnant and exhausted. I was also making a huge effort to play with my 3-year old daughter while trying to make sense and deal with the trauma that we had just gone through as a nation. She accidentally knocked over some dolls and cubes, and I automatically panicked and started having flashes of violent images, imagining the children who lost their lives or limbs or homes… I felt like I really needed to deal with this so that it doesn’t keep happening. My partner Toni Yammine (who is also my husband) and I were already working on an animated short movie dealing with heritage and culture. So I told him that night that it was our duty to change course and address the trauma that we just went through in a short film, not just for us but also for everyone who went through this tragedy. And this is how it all started.

You’ve chosen to tell this story from Mira’s perspective, a young girl who experiences a significant part of her childhood overshadowed by tragedy. What led you to see through the eyes of a child?

We wanted our main protagonist to be a little girl to show how such violence impacts your whole life even if it happens when you’re very young. This was inspired by a discussion I had with my 3-year-old daughter explaining to her what an explosion is and why explosions happen. I was heartbroken and devastated that I was being forced to have such a difficult conversation with her at such a young age. So we wanted to emphasize this unfairness through a child’s eyes. We wanted to show the idea of transgenerational trauma: the old version of Mira is inspired by my grandmother who lived through so much violence in her lifetime in Lebanon and is still traumatized from it today. These aren’t things you ever get over.

While deeply rooted in the Lebanese experience, your film also speaks a universal language of loss and resilience. Can you share more about how you navigated this interplay of specificity and universality during the creation process?

I find this question very interesting because universality was never our main intention. We wanted this to be deeply rooted in the Lebanese culture and experience. But I guess the feelings of loss and resilience are common to the human experience.

Describe the journey of crafting the visual language for “Peek-A-Boom.” What were some particular obstacles you encountered in visualizing the emotional depth of the narrative?

Our main goal for the visual language was for it to feel authentic. We wanted the characters to feel like they are people you could know, and the interiors and exteriors to feel familiar, to bring home the realness of what happened. So I drew from people and places I know. We also wanted to create a stark contrast between the scenes happening in the future, and the scenes happening in the present (at the time). So I emphasized this contrast through color and through illustration style: the colors are warm in the future, and very cold in the present. The animation style is clean and “computer-generated” in the future, while in the present the style is rough/organic and animated using the frame-by-frame technique.

Your work has always had a strong connection to children and their world. In what ways did this connection inform the creation of “Peek-A-Boom”?

My work in my children’s book “The Story of the Grilled Cheese Sandwich” and in our channel Lila TV is targetted AT children. I would say this short film was created FOR children. While it’s too hard for them to watch, they are the cause behind it.

Despite the heavy theme, “Peek-A-Boom” ends on a note of optimism, of a city and its people resilient and reborn. How did you approach incorporating this hopeful conclusion into the narrative?

We ended the film on a positive tone because we were struggling to be able to truly see this happening. We felt like we were at a dead-end, and were feeling desperate. So by drawing and animating a positive future, we were able to somehow see it and therefore believe in it, and this helped us have hope and feel resilient.

Personally, what was the hardest part of creating “Peek-A-Boom”? Were there moments where you had to step back or felt too close to the story?

There were many challenges for me on a personal level: first, I was in a terrible state of mind, feeling very depressed, so I was struggling to find the effort to create drawings and characters, etc. It was also my first time working on an animated short film (vs. the shorter corporate animations and animated music videos that I’m used to) so there was also a big learning curve. The 9-month production of the short film was also in parallel to my pregnancy and giving birth to my baby boy. I remember putting him to sleep and then taking my tablet to work on background designs while sleep-deprived. Finally, the hardest part was the “research” part: we wanted to portray the explosion as it happened, so we had to find a lot of footage from the explosion and from people who were very close to it. This was heartbreaking and I remember being in tears every time I watched these videos.

“Peek-A-Boom” has reached the hearts of many worldwide. Are there any responses or reactions from the audience that moved you or perhaps even changed your own perception of the film?

Internationally, I’m very happy that I was able to “humanize” what happened. While the explosion might just be another news item for most, people who watched the film abroad were able to really feel the repercussions that such an event can have on their fellow humans. Locally, I received a lot of feedback that the film helped them deal with the trauma and see it with fresh eyes. This is so heartwarming for me and makes me feel like our initial goal was accomplished: the cathartic effect that creating the film had on us is now spreading to others.

When the lights dim and the credits roll, what lingering thoughts or feelings do you hope “Peek-A-Boom” leaves in the minds of the audience?

I hope it will affect viewers in a way that whenever they hear about a similar tragedy in the news, (I hope they don’t but I’m also a realist) they feel more empathy towards the people victim of this violence. Maybe somehow the film plants the seed of compassion in their heads, blurring boundaries such as racism, or seeing “the other” as different and therefore not feel affected by their problems.

How do you envision the future of Lebanese animation and storytelling?

While still very far from having an animation industry in Lebanon, I hope that this film is one of the baby steps toward this. I hope teenagers watching the film know that they CAN have a career in Lebanon if they decide to pursue illustration and animation.

For more stories on art and culture from across the region, don’t miss our extensive coverage. Click here to explore more.