Therese Raffoul (Instagram), is an up and coming Lebanese designer and creative director based out of London. Her sculptural designs explore the hidden, or suppressed voices of women from our region’s past and imagine how they might express themselves in today’s world. Her creations delve into concepts of aggression, dark emotion, anger, fury and revenge, feelings that are not always portrayed in classic designs for women. Here, we talk to Therese Raffoul about her inspirations, her philosophy and her hopes for the future.

What first sparked your interest in the fashion design field?

I was very young, I started noticing that how people dressed was a big insight into who they were and how they interacted with life, getting dressed is such an intimate ritual.

Can you describe a moment or experience that profoundly influenced your creative direction and design philosophy?

I’ll never forget what I felt seeing Hussein Chalayan’s wooden table skirts. It solidified my desire to utilise my craft as storytelling and a communication method, and to see fashion outside of a product-based context.

How do your designs, which explore powerful emotions, many of which are perceived as negative when associated with women, aim to change traditional perceptions of women in fashion?

Representation for Arab women in fashion is very narrow and the gap between reality and what is marketed is immense. To solely represent the desirable side, to me, is a form of censorship and perpetuation of restrictive social parameters. I’m interested in the potency of the mundane details of daily life, which are more insightful and curious than the elaborate fairy tales designed to represent women.

“Barking and biting back” is a powerful concept. Can you elaborate on the symbolism behind this idea and how it relates to your exploration of an Arab woman’s shadow side?

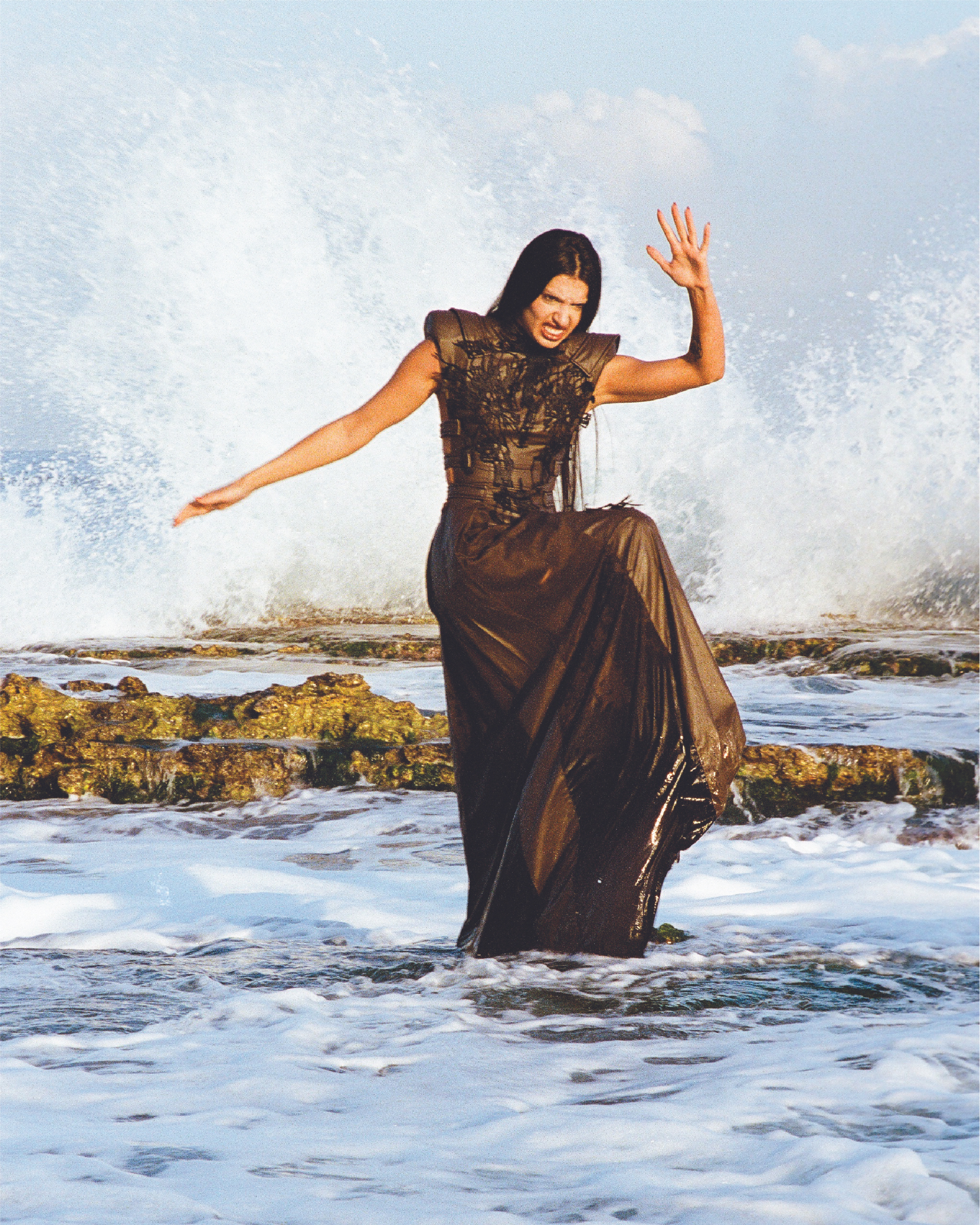

I started looking at images of animals mid bark, and as odd as this might sound, I felt like if I were to unleash my own shadow-side, it would be similar. To release such a primal feeling, as a woman, is subject to scrutiny. Once you become undesirable, society’s behaviour towards you changes because complacency is so pragmatic. The collection was cathartic as I built this narrative and these characters that are militantly retaliating against that censorship. That is why there are explicit militant/battle references in the editorial, it’s almost satirical how much one has to fight to not constantly be an object of desire, in peace, amongst other fights.

How has your Lebanese heritage and education in London influenced your design aesthetic and perspective?

My design language pulls from observation, it’s like being a kid, putting your ear to the door when older family members are sharing secrets, and suddenly the puritanical world you knew never was. All I’ve observed was in Lebanon for the most part and in the micro social dynamics, in those crevices, that’s where I find my biggest references. My education in London was invaluable as it allowed me to observe so many peers’ way of working, seeing their diverse and dynamic processes and it has pushed me to look for sharper tools, it has by far been my biggest education.

Can you tell us about the hidden symbols and words within your designs and how they contribute to your story?

I was researching how calligraphy manipulates letters in a structural way. I was intrigued by how one could conceal a word, a message, by making it slightly less easy to read. I wanted to translate that directly into the jewellery for example, and as for the clothes, the way I abstracted maps and turned them into embroidery was a way of hiding a destination in plain sight.

Tell us about your collaboration in jewellery design. What inspired you to venture into this field?

I approached Eva Wuyang, whose practice consists of making jewellery out of clay in organic shapes, it took jewellery out of the traditional luxury context and allowed it to be a more subversive language. I asked her to interpret the Arabic sentence “ارني اسنانك” and use the shape of the letters as teeth, it was really beautiful to see how she created it as a non-Arabic reader or speaker.

If you could time-travel wearing your designs, which era would you pick, and how do you think people from that time would react to your creations?

I would visit the Oracle of Delphi so the priestess Pythia could give me some good tips for my next life, after maybe being killed for dressing that way [lol].

For more fashion stories from the region and the world, like that of Therese Raffoul, visit our dedicated archives.